By John Allyn

Introduction: John Allyn is a member of the BONT Board and author of numerous articles on the BONT website. His inspiration for telling the story of Minnesota troops in Nashville began with the magnificent Howard Pyle painting in the Minnesota state capitol and the Minnesota monument at the National Cemetery in Nashville, both of which memorialize the fact that Minnesota sustained more casualties at Nashville than at any other battle where her troops fought, and that they played pivotal roles during both days of the Battle of Nashville.

Part 1

Introduction

Above: In 1920 the State of Minnesota erected a monument in the Nashville National Cemetery on Gallatin Pike. The monument honors soldiers from Minnesota who are buried there. It reads: “Erected A. D. 1920 by the STATE OF MINNESOTA in memory of her soldiers here buried who lost their lives in the service of the United States in the war for the preservation of the Union 1861 – 1865.”

Some years ago I was on a Nashville battlefield tour, the traditional Gray Line bus and all that. The tour leader was doing an excellent job. As we approached Shy’s Hill from the east (on Battery Lane, for those familiar with Nashville streets) the tour leader pointed out the hill and noted that we were viewing it from more or less the same perspective as the famous Howard Pyle painting of the battle.

At which point the following discussion took place between our tour leader and one of our tour participants, a Nashville dowager with a DAR Regent look about her:

Dowager: “A painting? Where is this painting?”

Tour leader: “It’s in Minnesota.”

Dowager: “What is it doing there? We must get it back!”

Tour leader: “It’s a mural in their State Capitol. It was paid for by the people of Minnesota. I don’t think that it’s going anywhere anytime soon.”

Dowager (huffily, and not admitting defeat): “Well, I can’t see why they should have our painting.”

Above: Howard Pyle, a noted 19th century illustrator, painted this mural in 1906. The original is located in the governor’s Reception Room in the Minnesota State Capitol in St. Paul, Minnesota. It depicts the attack on the afternoon of December 16, 1864 by the 5th and 9th Minnesota Infantry Regiments on the Confederate line just to the east of Shy’s Hill, which is seen in the background. The area depicted is just east of Granny White Pike and just south of modern Battery Lane, on modern McArthur Ridge Court.

Above: Howard Pyle, a noted 19th century illustrator, painted this mural in 1906. The original is located in the governor’s Reception Room in the Minnesota State Capitol in St. Paul, Minnesota. It depicts the attack on the afternoon of December 16, 1864 by the 5th and 9th Minnesota Infantry Regiments on the Confederate line just to the east of Shy’s Hill, which is seen in the background. The area depicted is just east of Granny White Pike and just south of modern Battery Lane, on modern McArthur Ridge Court.

There is a very simple reason why Minnesota has the painting. Troops from Minnesota played a key role in the battle. Moreover, the State of Minnesota sustained more casualties at the Battle of Nashville than it did in any other Civil War engagement. Four Minnesota infantry regiments were in the forefront of the fighting on both days of the battle, and two others had peripheral roles in the battle. Indeed, on both days Minnesota regiments made the initial breaches in the Confederate lines.

Minnesota wasn’t a big state in 1861. The 1860 census shows it as the second smallest state in the Union, followed only by remote Oregon. It was very much a frontier state, populated mostly by emigrants from the other states of the Northwest and from Northern Europe. Unlike Illinois, Indiana, or Ohio, very few Southerners settled there. Western Minnesota was still very much the domain of the Sioux. Because of this, Minnesota was the only non-slave state to sustain significant civilian casualties and property losses during the Civil War. Between 400 and 800 settlers, many of them women and children, were killed in the Dakota War of 1862, and most of the settlements in the Minnesota River Valley were destroyed.

Minnesota had 24,000 men who served during the Civil War. Of these, 6,000 were either “citizen soldiers” – non-federalized troops comparable to militiamen in other states — who fought in the Dakota Uprising in Minnesota, or federalized cavalrymen who exclusively fought Indians in the Dakota and Montana Territories. Minnesota provided approximately 18,000 soldiers to the Union Army for operations in the South. To put this into context, Tennessee, the eleventh star on the flag of the Confederacy, provided 31,000 soldiers for the Union according to the indispensible Tennesseans in the Civil War. Of course, this was in addition to 186,000 Tennesseans who served in the Confederate Army. There were eleven federalized infantry regiments from Minnesota, serving from the western frontier to the Atlantic coast. Six of those saw action in the Nashville campaign. Over the next few months we’ll give you their histories.

Above: My encounter with the lady on the bus prompted me to track down this cartoon by Bill Mauldin (the famed portrayer of Willie and Joe during the Second World War) which depicts the perils of ancestor worship, particularly where that ancestor was a soldier.

________________________________________

Part 2

The 11th Minnesota Infantry

“They also serve who only stand and wait.” John Milton, Paradise Lost.

The 11th Minnesota Infantry was formed in the summer of 1864 in response to President Lincoln’s last call for volunteers. The regimental history proudly notes that every man was a volunteer, and that it included no draftees. It arrived in Nashville and initially was directed to detail men to guard supply trains running from Nashville to Chattanooga.

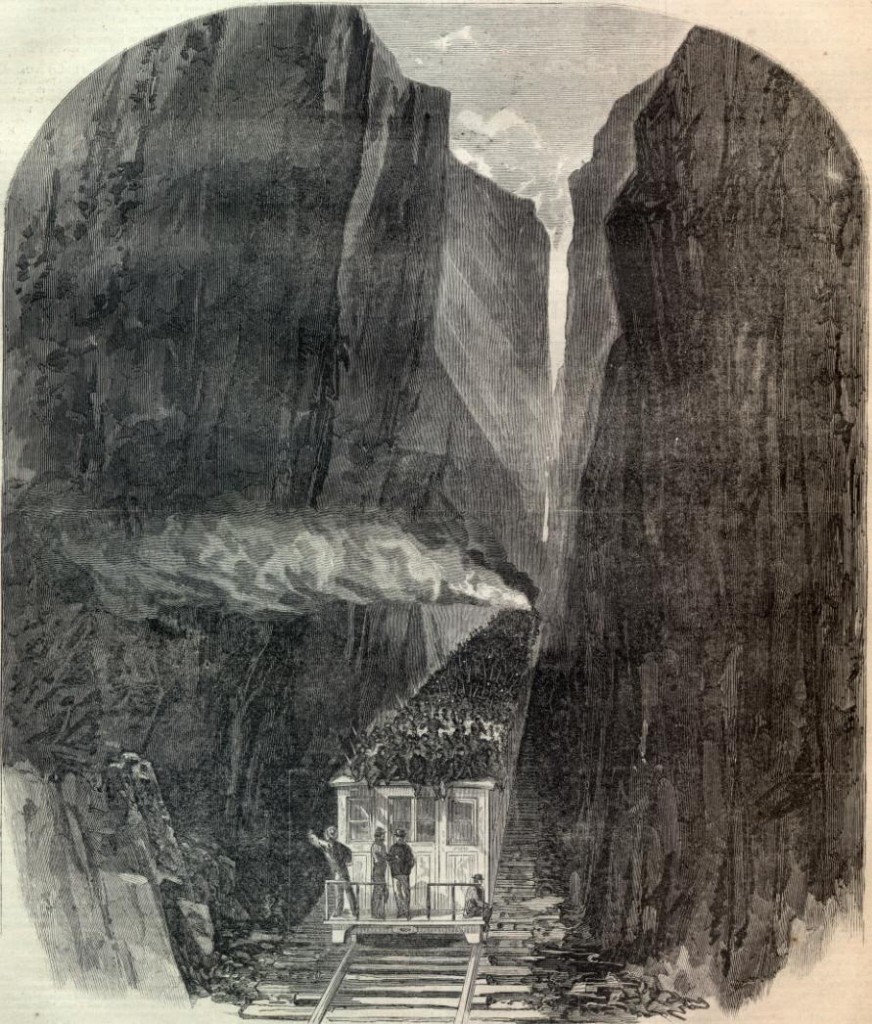

Above: This rather fanciful sketch of a troop train passing through the Cumberland Mountains on the Nashville & Chattanooga Railroad appeared in Harper’s Weekly in 1863. While troops did on occasion travel on the roofs of the cars, there is no cut either so deep or so narrow on the line.

On October 12, 1864 the regiment was assigned to guard the Louisville & Nashville Railroad from Edgefield Junction just outside of Nashville north to the Kentucky line. The regimental headquarters and three companies were based in Gallatin, described as “a lively little city”. Single companies were placed at Edgefield Junction (modern Amqui), Saundersville (between Goodlettsville and Gallatin), Richland (became Portland in the 1890’s when the Post Office noted that there were two Richlands in Tennessee), Buck Lodge (north of Portland), and Mitchellsville (on the Kentucky line).

Above: South Tunnel was an extremely vulnerable point on the rail line between Louisville and Nashville. The remains of a Federal fort on can be found on the hill on top of the tunnel. As you can see, it is still in use today, a commentary both on nineteenth century engineering practices and the rock-breaking skills of Irish immigrant laborers. This photograph is of the south portal of North South Tunnel, looking north. © Kevin Comer 2009. Used with permission.

Two companies were stationed at South Tunnel, a key strategic point halfway between Gallatin and Portland. South Tunnel actually consists of two tunnels – called North South Tunnel and South South Tunnel — about four hundred feet apart. While this confusing, there is an explanation. There is also a North Tunnel on the Louisville & Nashville. It is through Muldraugh’s Hill near Maysville, Kentucky.

The South Tunnels were laid out by engineers using transits and stakes, and were built by Irish immigrants using star drills and black powder, as dynamite and steam drills had not been invented yet. It was completed in 1859, and is still in use today. In August, 1862 John Hunt Morgan destroyed South South Tunnel by pushing several burning freight cars into it. The railroad line was closed for more than three months with supplies being moved by wagon from the railhead at Richland/Portland to the railhead at Gallatin. At this time the Federals built forts on top of each of the tunnels and heavily garrisoned them for the duration of the war.

Above: Google Earth picture of the South Tunnels. The portals have been marked on the map. Forts were built on top of each tunnel, but their remains cannot be seen due to the summer foliage. The site can be visited after an overland hike. However, the photographer who took the train picture above recommends going in a group and going armed as this is meth and moonshine country. Click to enlarge

The Confederate advance into Middle Tennessee in November and December, 1864 raised Federal concerns about the rail supply line from Louisville. The western terminus of the Nashville & Northwestern Railroad at Johnsonville had been destroyed by Forrest in early November, and when it came up in December Hood’s army cut the line at Belle Meade. Low water on the Cumberland River limited its use as a supply line during the winter months, and this was compounded by the fact that Forrest’s cavalry set up a battery at Bell’s Bend which effectively eliminated the river as a supply line. Because of these events, the L & N became the sole supply line for the Federal forces gathering in Nashville.

Given this concern over the safety of the railroad, the regiment stood to arms each day from 3 am until sunrise with much firing at shadows and shapes. A few days before the Nashville battle, word was received of a possible attempt by guerillas to attack the tunnels. The three companies stationed at Gallatin were hurriedly ordered into boxcars – well-dunged from having previously been used for hauling sheep — for the six mile ride to South Tunnel. The soldiers debarked into a night which looked like “a stack of black cats” and went into line. However, “nothing tuned up but the sun, which, by the way, appeared to be unusually slow that morning” and the troops were back in Gallatin by noon.

When the main battle began the sound of the cannons could be heard in Gallatin. Some members of the regiment went to Nashville to watch the show, but none took an active part. Following the battle the Eleventh had its first view of Confederate soldiers, as train after train of prisoners went north.

The regiment continued to serve on the railroad line until June, 1865, when they were relieved by a regiment of United States Colored Troops. The Eleventh returned to St, Paul and mustered out the next month.

Part 3

The 8th Minnesota Infantry

“The Indian Regiment”

The 8th Minnesota Infantry was formed on August 1, 1862. This coincided with the beginning of the Sioux Uprising in Minnesota, and the new regiment was parceled out in dribbles and dabs across the state, providing garrisons for the small settlements and frontier forts.

Then regiment served in this manner until the spring of 1864, when it was assembled to participate in Colonel Alfred Sully’s Missouri River Expedition against the Sioux. The regiment mustered at Paynesville, Minnesota on May 24, 1864 and received their regimental colors. They were given horses at the same time. On June 5, 1864 Colonel Minor Thomas of the 8th Minnesota led a column composed of that regiment, six companies of the 2nd Minnesota Cavalry, two sections of artillery, and a company of Indian scouts, 2,100 men in all, from Paynesville to the northwest, up the valley of the Minnesota River.

Alfred Sully, the son of a noted watercolorist, graduated from West Point in 1841. In the years preceding the Civil War he acquired a considerable reputation as an Indian fighter. At the time of the Sioux uprising in August, 1862 he was a cavalry commander in the Army of the Potomac. He was transferred west to Minnesota where he led a campaign against the Sioux and their allies which took the 8th Minnesota to eastern Montana.

When the column reached the headwaters of the Minnesota River at Lake Travers near the border between Minnesota and present day North Dakota, it veered to west, travelling overland until it struck the Missouri River in early July, 1864. At that point it joined with the remainder of Sully’s army. On July 19 the combined columns proceeded west, ending up in the headwaters of the Knife River in the Killdeer Mountains. They came upon a large Indian encampment and attacked it on July 28, 1864. Artillery and military discipline gave the Federal forces the advantage in what came to be called the Battle of Killdeer Mountain, and the Indians were driven off. The 8th Minnesota participated in the main action, and four of its companies were used to pursue the defeated tribesmen into the hills to the west.

This 2008 photograph shows the Killdeer Mountain battlefield as it appears today. It is in western North Dakota, just to the east of the present day Badlands National Park. Brigadier General Alfred Sully attacked and dispersed a large Sioux encampment here in July 28, 1864. The 8th Minnesota, acting as mounted infantry, played a prominent role in the battle.

The expedition continued to the west, passing through the North Dakota Badlands. While passing through the Badlands, they fought another battle with the Sioux at a place called Waps-chon-choka. The Indians were once again defeated, and following a pursuit of several days the Sioux dispersed in all directions.

At this point the troopers were in the easternmost part of the Montana Territory, and were very short of water. They moved north, and on August 12, 1864 they struck the Yellowstone River near what is now Sidney, Montana. Proceeding downriver, they reached Fort Union on the Missouri River. The Eighth was then sent north to the Canadian border in the hope that they would encounter the Sioux who had been driven out of the Badlands. The regiment did not encounter any hostile Indians and upon its return to Fort Union the bulk of the regiment was directed to return to Minnesota for assignment to the South. However, around two hundred men were sent two hundred miles to the west – deep into the heart of the Montana Territory – to succor an emigrant train that was being besieged by the Sioux.

The main body arrived at Fort Snelling in St. Paul on October 15, 1864, and received orders directing it to join the XXIII Army Corps in Tennessee. The regiment travelled by steamboat and rail to Nashville. The highlight of the trip occurred in southern Indiana when the train carrying the regiment derailed. The soldiers were travelling in cattle cars, and as they pulled themselves from the wreck they were met by a local lady who inquired, apparently in the hopes of a low cost meal, whether there were any injured cattle. The “cattle” checked amongst themselves and advised the lady that no one had been hurt, least of all any livestock.

The bulk of the regiment arrived in Nashville in late November. Waiting for them was the 200 man contingent that had been sent deeper into Montana; it had come down the Missouri river in a steamboat from Fort Union to St. Louis and had come on to Nashville by rail. Since the XXIII Corps was at that point retreating from Pulaski to Nashville before Hood’s army, the 8th Minnesota, being a veteran unit, was sent to Murfreesboro to bolster the garrison there. Colonel Thomas, by reason of his experience in Virginia and Mississippi (with other Minnesota regiments) and on the Great Plains, was made a brigade commander.

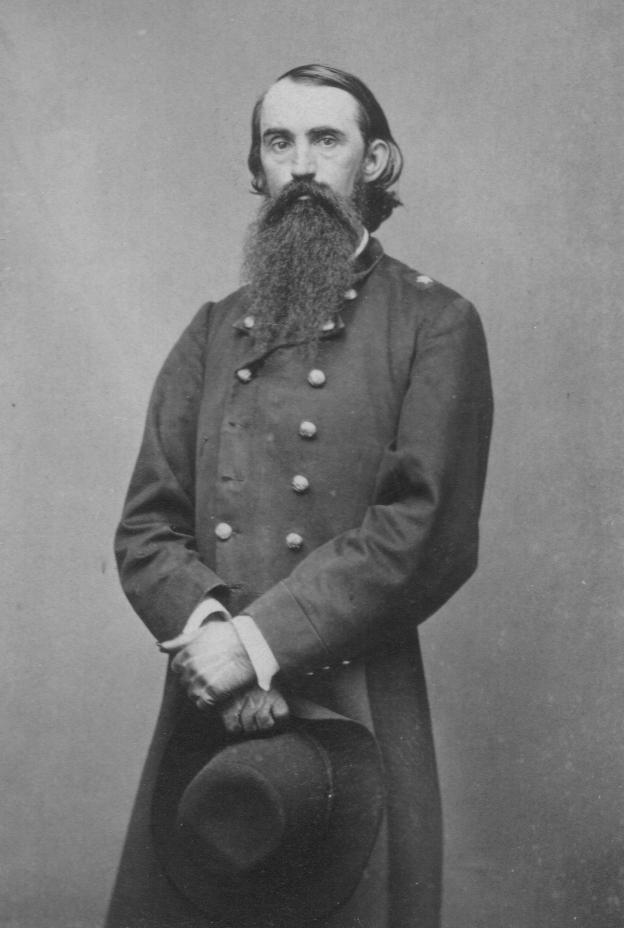

ABOVE: Colonel Minor Thomas, commander of the 8th Minnesota Regiment, at the time of his discharge in July, 1865. Thomas started the war as a lieutenant in the 1st Minnesota Infantry and served in three separate Minnesota regiments, two as the commanding colonel. He fought in Virginia, Mississippi, the Dakota Territory, the Montana Territory, Tennessee, and North Carolina. He was a brigade commander in the last two campaigns. He was brevetted a Brigadier General of Volunteers in March, 1865.

In the meantime, the Confederate Army of Tennessee, having fought the bloody Battle of Franklin, put Nashville under siege. John Bell Hood believed that if he divided his already badly outnumbered army and sent a significant body of troops to Murfreesboro he could somehow (a) get Sherman to retreat from Georgia, or (b) get Thomas to come out of the Nashville fortifications which would give Hood an opening to get into Nashville. Sherman at this point was halfway across Georgia. He was effectively incommunicado and completely independent of the Louisville – Nashville – Chattanooga – Atlanta supply line. He was thus beyond Hood’s influence. For his part, Thomas would come out of the Nashville fortifications in his own good time, and hindsight tells us that this is not something that Hood really should have wanted.

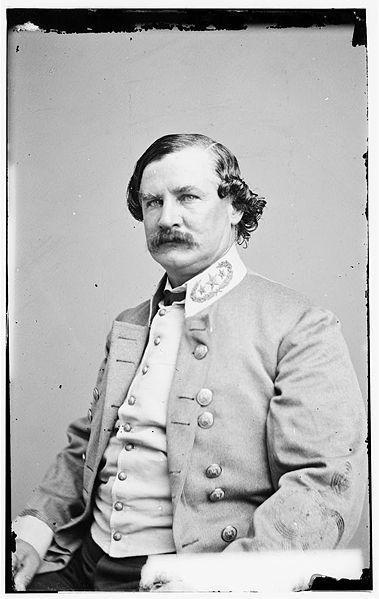

Major General William Bate. Bate was a lawyer from Gallatin in Sumner County who had served as an officer in the Mexican War. At the beginning of the Civil War he raised the 2nd Tennessee Infantry and was promoted to brigade and divisional command. He was wounded at Shiloh and during the Atlanta campaign. Postwar, he served as Governor of Tennessee (1883 – 1887) and as a Senator from Tennessee (1887 – 1905). He died in 1905.

One of Forrest’s divisions was already on the railroad between Murfreesboro and Nashville, burning bridges and capturing blockhouses. On December 2, 1864, Hood sent Bate’s infantry division, part of Cheatham’s Corps, to Rutherford County to do the same. Two days later Bate arrived and his’ division attacked Blockhouse No. 7, which protected the railroad bridge across Overall Creek northwest of Murfreesboro.

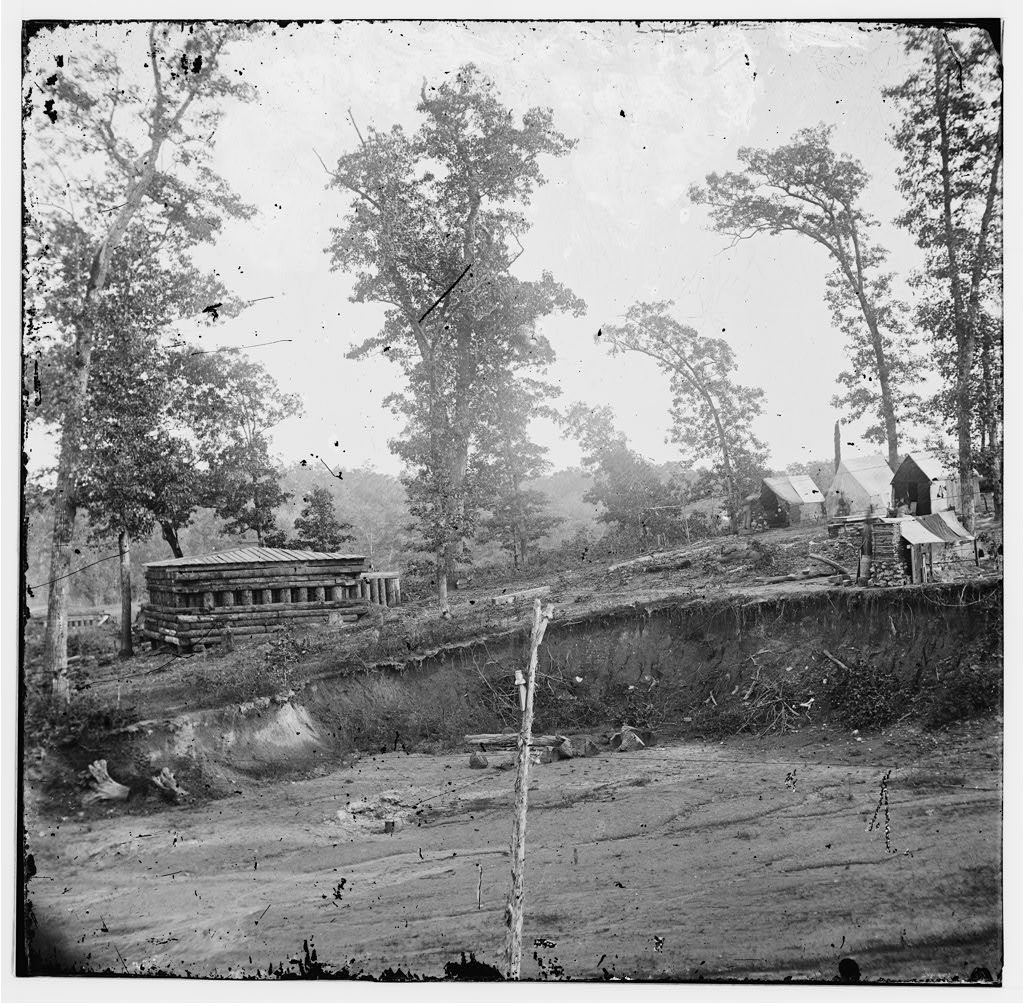

While the location of this particular blockhouse is unknown, it was on the Nashville & Chattanooga rail line that ran through Murfreesboro and is typical of the blockhouses located at critical points along the line. While the log and earth construction protected against small arms fire, the blockhouses were extremely vulnerable to artillery fire. After the Confederates came up to Nashville General Thomas ordered the blockhouses between Nashville and Murfreesboro to be evacuated, but as is always the case in the military, someone did not get the word.

The Federal garrison in Murfreesboro – including the 8th Minnesota — numbered about 7,800 men and was under the command of Lovell H. Rousseau. The garrison occupied Fortress Rosecrans, a huge earthwork constructed during the buildup for the Atlanta campaign for the purpose of defending the railroad. Around noon on December 4, observers in the fortress noted smoke and the sound of gunfire to the northwest, and the 13th Indiana Cavalry was sent to investigate. The Indiana cavalrymen came upon Bate’ attack, set up a skirmish line on the south bank of the creek, and sent back to Fortress Rosecrans for reinforcements.

ABOVE: Major General Robert H. Milroy was the tactical commander of the forces in the Fortress Rosecrans garrison. Milroy is best remembered for losing almost his entire division to Ewell’s Corps in the Second Battle of Winchester on June 15, 1863, a run up to the Battle of Gettysburg. He was one of the few in his force to escape capture, and his Gideon Pillow-like flight led to a court of inquiry. He was exonerated but was sent to the backwaters of the west where it was thought he could do little harm. He remained bitter about this until the end of the war. This was illustrated in his report on the December, 1864 actions around Murfreesboro where he gave his patron General Rousseau “my most grateful acknowledgments for his kindness in affording me the two late opportunities of wiping out to some extent the foul and mortifying stigma of a most infamously unjust arrest, by which I have for nearly eighteen months been thrown out of the ring of active, honorable, and desirable service.” He did do well, but the Federal victory was not so much the result of his tactical prowess as it was the consequence of the collapse of the Confederate infantry.

The reinforcements, consisting of the 8th Minnesota plus two other infantry regiments – the 61st Illinois and the 174th Ohio — and a section of artillery from the 13th New York battery, were led by Major General Robert H. Milroy. Milroy placed the 8th Minnesota and the Indiana cavalry on his right in front of the blockhouse, which was on the south side of the creek. The other two infantry regiments crossed the creek on the highway bridge (the modern Old Nashville Highway) about a half mile upstream. Expecting to confront Forrest’s cavalrymen, they were surprised to discover that they faced Confederate infantrymen from Finley’s Florida Brigade. The Floridians were driven back but the Federal advance was stopped by a counterattack by Henry Jackson’s Georgia brigade, which had earlier been occupied with wrecking the railroad. The Eighth could not find a ford over the creek, and so its role was limited to exchanging desultory fire with Confederate sharpshooters on the north side of the creek. At dusk the Federals (except the garrison of the blockhouse) returned to Fortress Rosecrans and the Confederates moved to Stewart’s Creek, five miles to the north.

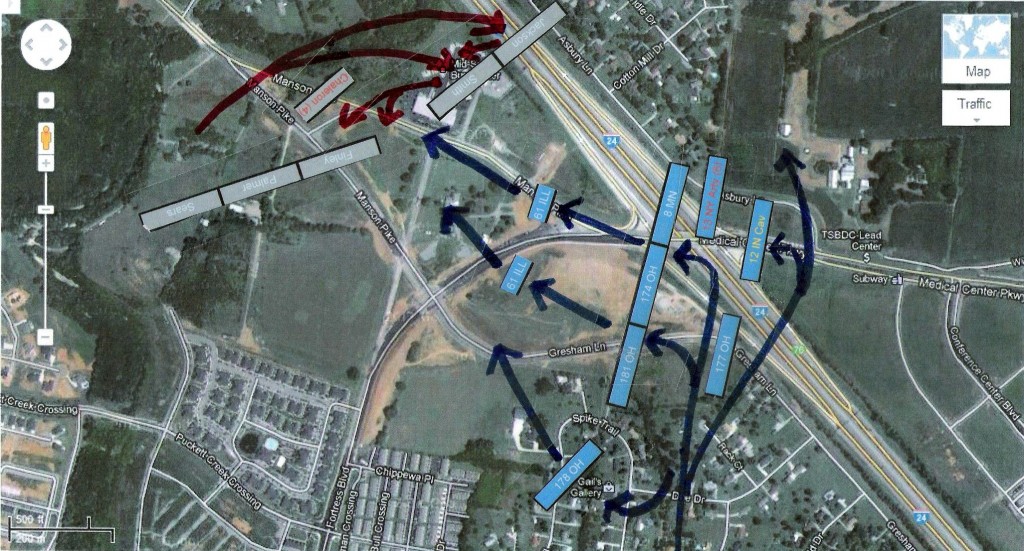

ABOVE is a Google Earth view of the Overall Creek battlefield. The battlefield has not been developed yet, and is more or less in the same condition that it was in 1864. The Creek meanders from bottom to top through the middle of the view; the banks are wooded. The 8th Minnesota and the 12th Indiana Cavalry were deployed on the south side of the Creek astride the railroad line, which runs parallel to and slightly west of the modern Nashville Highway. This highway did not exist in 1864. Since no ford could be found, neither unit crossed the creek. The blockhouse was on the south bank of the Creek east of the railroad bridge, and is marked on the map. The 174th Ohio and the 61st Illinois advanced north on the Old Nashville Highway and drove back Finley’s Florida Brigade. Smith’s Brigade same up from the north and held off the advancing Federals so that Charleron’s guns could be safely withdrawn.

On December 6 Bate was joined by Bedford Forrest with two cavalry divisions under William H. “Red” Jackson and Abraham Buford. Forrest assumed command. The Confederates were also reinforced by two more infantry brigades, Sears’ Mississippi Brigade and Palmer’s Brigade composed of North Carolinians, Tennesseans, and Virginians. Buford’s Division was sent to the east leaving the Confederates with a force of approximately 1,600 infantry, 2,100 cavalry, and four guns. On the sixth Forrest demonstrated on Wilkinson Pike (now Manson Pike) a few miles to the northwest of Fortress Rosecrans, hoping to draw the Federals out into the open.

They did, but from a different direction. On the next morning Milroy came out from the fortress on Salem Pike, which runs southwest from Murfreesboro to Eagleville. He led a force of seven regiments formed in two extemporized brigades totaling 3,325 men and six guns. Colonel Thomas commanded the first brigade, composed of two regiments with combat experience — the 8th Minnesota and the 61st Illinois — and two green regiments, the 174th Ohio and the 181st Ohio. The two brigades marched out, Thomas’ brigade in the lead. Almost immediately they began skirmishing with Confederate cavalry vedettes. They reached the home of a Mr. Spence. Mrs. Spence gave General Milroy a fairly accurate account of the Confederate dispositions, and for this service the General detached a company to take “a drove of sixty fine, fat hogs” from the Spence farm back the Murfreesboro. Milroy rationalized this on the basis that the Confederates would have taken the hogs anyway.

With this intelligence in hand, Milroy turned north and headed towards Wilkinson Pike, initially on country lanes and then overland. His intention was to keep his troops between the Confederates and Fortress Rosecrans. Forrest anticipated this, and drew up his infantry in a line running north-south in a tree line. The Confederate left was on Wilkinson Pike a short distance east from where the road crossed Overall Creek. The Confederate right was anchored on the creek. Forrest expected the Federals to attack this line head on, and as they did so he planned to have Jackson’s cavalry division attack them in the flank from the north of Wilkinson Pike.

The Federal forces advanced through open fields towards the Confederate line, coming under artillery fire as they did so. This fire was accurate, and Milroy ordered his troops into a cedar brake where they would not be visible to the Confederate gunners. The 8th Minnesota was in the advance; its historian said that this was because it was “regarded as the best drilled and most reliable regiment in the command, its having been in the Indian War giving it a greater reputation than the same service in the South would.” Indeed, it was referred to as “the Indian Regiment” by the other troops.

The Federals continued their advance to the north under cover. When they emerged from the woods they were astride the Wilkinson Pike, and as they began their advance they were in a position to outflank the Confederate infantry. The 61st Illinois formed a skirmish line in advance of the 8th Minnesota, which was north of the Pike, and the 181st Ohio, which was south of the Pike. The 174th Ohio formed on the left of the 181st Ohio. The Confederates shifted units to the north of the Pike, but in doing so left a gap of 75 to 100 yards between Finley’s Florida Brigade and Benton Smith’s brigade of Georgians and Tennesseans. The 8th Minnesota headed for this gap, giving an Indian yell. Jackson’s Georgia Brigade was brought back to fill the gap, and in so doing fired into the rear of the Floridians, who were wearing blue Federal overcoats captured at Franklin. With the 8th Minnesota firing into their front, the Floridians began to retreat in some disorder. Forrest attempted to rally them, calling on a color bearer to turn and rally. When the color bearer failed to do so, Forrest shot him and seized the color himself. This had no effect on the Floridians and the rest of the Confederate infantry, seeing the line broken at the center, also began to retreat. Smith’s Brigade, which maintained good order, covered the retreat along with Jackson’s cavalrymen.

ABOVE is a Google Earth Picture of the Battle of the Cedars battlefield. The site of the Battle has been changed beyond recognition by the construction of the Medical Center Parkway exit off of Interstate 24 in Murfreesboro. The only constant is that Manson Pike roughly follows the former route of Wilkinson Pike west of the Interstate. The Confederate infantry line ran SSW in a tree line from Manson Pike (Wilkinson Pike in 1864) to Overall Creek. Originally Finley’s Florida Brigade was on the left, with Palmer’s and Sears’ Brigades to its right and Smith’s and Jackson’s Brigades in reserve. Keep in mind that by 1864 a Confederate brigade was about the same size as a Federal regiment. Milroy’s Federals approached the Pike from the south, concealed from Confederate view by a thick wood. Thomas’ brigade (of which the 8th Minnesota was a part) was in the lead. They would have come out of the woods about where the Interstate crosses Manson Pike on this map. They formed into line, with the 8th Minnesota was north of the Pike; the 174th and 181st Ohio were to its left, south of the pike. The 61st Illinois formed a skirmish line to their front. A second brigade consisting of the 177th and 178th Ohio and the 13th Indiana Cavalry (Dismounted) was in reserve behind Thomas’ brigade and was not involved in the action. Since the 8th Minnesota was in a position to outflank the Confederate line, Bate moved Smith’s and Jackson’s reserve brigades from the confederate rear to a line north of the pike. In doing so they unfortunately left a 75 yard gap in the line between Jackson’s and Finley’s Brigades.

The action was costly for the Confederates. General Bate reported that his division had lost 19 killed, including the lieutenant colonel of the 29th Georgia of Jackson’s Brigade, and 73 wounded. Milroy reported capturing 207 Confederate prisoners, including 18 commissioned officers. The Federals also captured two Napoleons from Slocomb’s Louisiana Battery, then under the command of a Lieutenant Charleron, and the colors of the 1st/3rd Florida Regiment. Forrest did not make a separate report f his casualties.

Federal casualties totaled 22 killed and 186 wounded. The 8th Minnesota bore the brunt of this, losing 13 men killed and 77 men wounded, including The Eighth had 13 men killed, and 3 officers and 74 men wounded out of a force of 29 officers and 529 men engaged. Lieutenant Colonel Henry C. Rogers, temporary commander of the regiment, was seriously wounded in the arm; he ultimately died of his wound in 1871 after serving a term as Minnesota’s Secretary of State.

Following the Battle of Nashville, Thomas’ Brigade, including the 8th Minnesota, was ordered to march cross country to north Alabama where it joined the XXIII Army Corps. The XXIII Corps went up the Tennessee and Ohio Rivers via steamboat, overland to Washington by rail, and by sea by ocean packet to Wilmington, North Carolina which had been recently been captured by the Federals. The 8th Minnesota moved inland, and on March 19, 1865 participated in the Battle of Kinston. In mid-July, 1865, the regiment left North Carolina and was mustered out at St. Paul in early August, 1865. Twenty-five years later the regimental historian gave this valedictory on the regiment:

“The Eighth regiment was fortunate in the character of its material; fortunate in the harmony within; fortunate in the variety of its service, mounted and on foot, railroad and steamship; fortunate in the wide extent of the United States it visited at Uncle Sam’s expense . . . ; fortunate that in the last ear of the war it traveled more miles and saw a greater variety of service and country than any other regiment in the United States Army; fortunate that the end of its enlistment saw the end of the Rebellion and a saved country.”

Nothing further need be said.

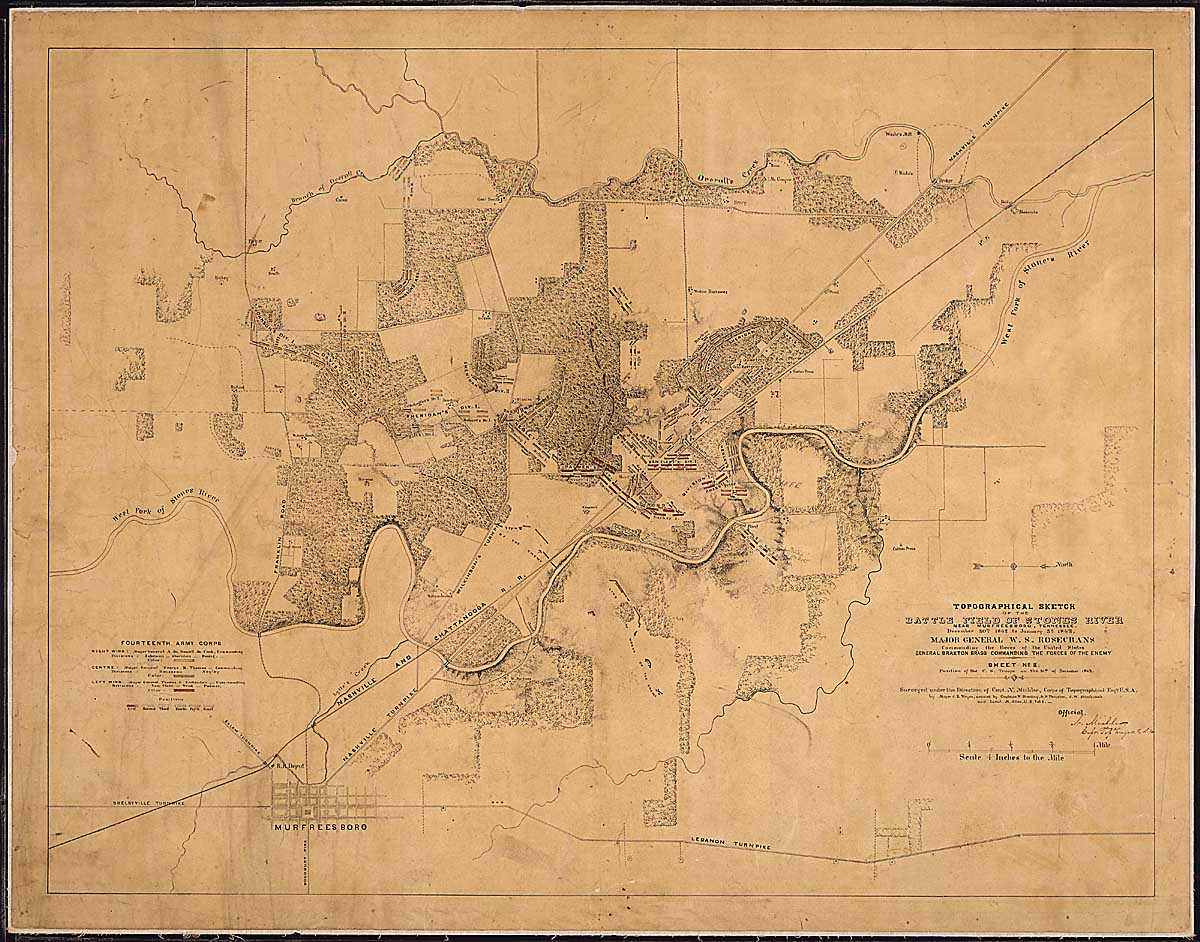

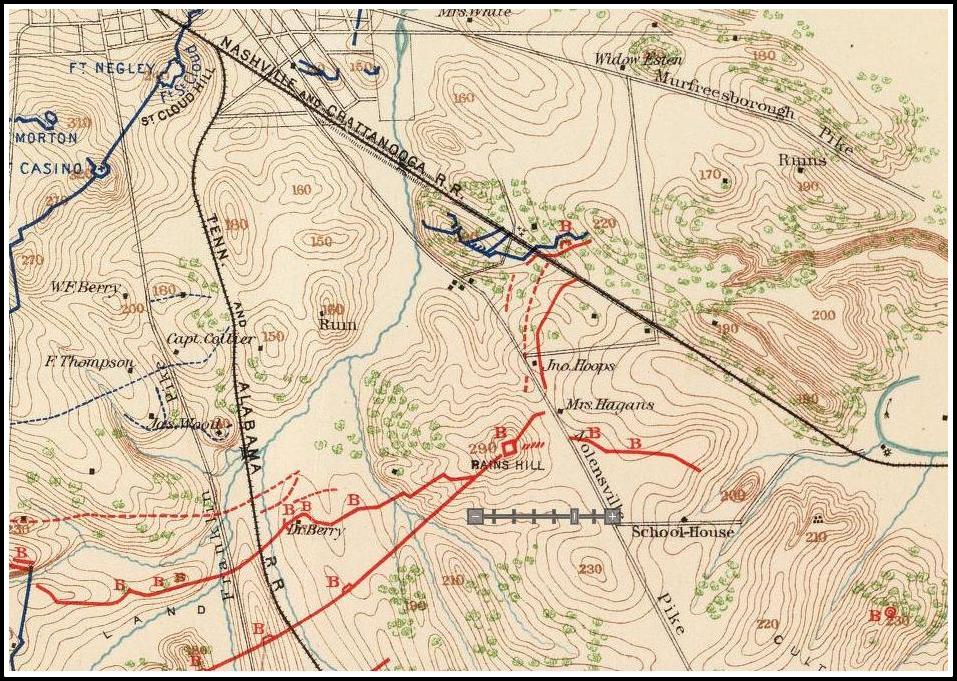

Period Map of the Murfreesboro Area (Click to Enlarge) This map illustrates the Battle of Murfreesboro fought December 31, 1862 – January 2, 1863 using a map that was made late in the war. It has an unusual orientation — west, not north, is at the top of the map. It does show the two 1864 battlefields discussed in this article. The Overall Creek battlefield is in the top right corner — the blockhouse that the 8th Minnesota defended is shown just to the east of the railroad. The Cedars battlefield is in the top center. The Confederate line followed the tree line along Overall Creek. Milroy’s troops passed along the front of the Confederate line using the woods just to the east (below on the map) as concealment. Once the Union forces came out of the woods they had less than 200 yards of open ground to cover before they hit the Confederate line.

Part 4

Minnesota Regiments At Nashville

“The Also Rans: Minnesota Replacements At The Battle of Nashville”

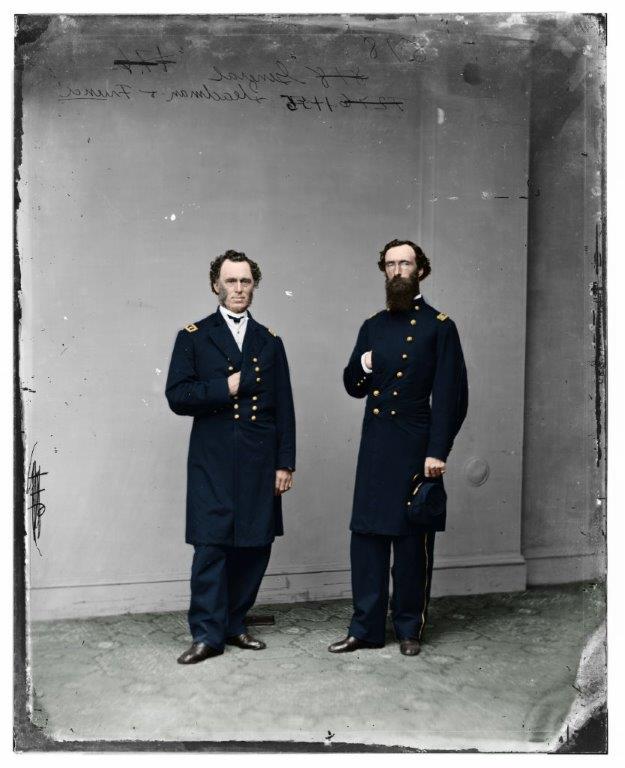

Above: Major General James B. Steedman (left) and his Adjutant, Major Seth B. Moe, 1864. Steedman was born in Pennsylvania in 1817. He worked as a printer in that state and in Kentucky and Ohio and then served in the Texas War of Independence. In the 1840’s he was active in Democratic politics and was a delegate for Stephen A. Douglas at the 1860 Democratic Convention in Charleston. In 1857 he was named a Major General in the Ohio State Militia, apparently based on his service in Texas. In 1861 he organized and commanded the 14th Ohio Infantry and served ably in brigade and division command in the Army of the Cumberland through 1864, most notably at Chickamauga in 1863. At the time of the Battle of Nashville he commanded the District of Etowah, a corps-sized unit charged with defending lines of communication from Georgia to Kentucky. His troops comprised the force attacking the Confederate right flank. After the war he served in various reconstruction governments in the South. He returned to Ohio in 1876 and served as a Democratic representative in the Ohio State Legislature until his death in 1883. Moe was a railroad man from northwestern Ohio who acted as Steedman’s principal staff officer during the war. Public domain.

Introduction

The first day’s action on the Confederate eastern flank has generally been given the short shrift by historians: untrained black troops were sent to attack a tiny Confederate brigade in a little fort and were driven off in complete disorder after sustaining terrible losses. What actually occurred is a little more complex and what’s more, we have a tenuous (and somewhat inglorious) Minnesota connection with the action. So let’s begin . . .

“Veteranizing” the 2nd Minnesota Infantry Regiment.

The record of the 2nd Minnesota Infantry is the story of the Army of the Cumberland. With the exception of Stones River, the Regiment fought in every engagement of that Army from Mill Springs to Bentonville.

The Regiment re-enlisted — “veteranized” is the correct term — for the duration of the war in December, 1863. A number of benefits came with re-enlistment:

- Each soldier who re-enlisted got a $400 federal bonus. This was big money in 1864 dollars, almost a year’s pay for an unskilled worker. States tossed in additional bonuses but they varied.

- The soldier received a 30 day furlough.

- The soldier got the title ‘veteran volunteer’ and there was a special chevron that he was entitled to wear on his uniform.

- If three-fourths of the regiment reenlisted then it went home on furlough as a group to recruit additional members and the regiment would thenceforth be designated as a “veteran volunteer” unit.

The 2nd Minnesota had its re-enlistment leave in early 1864, and recruited many new men at that time. It returned to Georgia in time to participate in the Atlanta campaign. The draft, however, continued and by the late fall of 1864 two groups of new soldiers – draftees, substitutes, and a sprinkling of volunteers – had been assembled at Fort Snelling in Minnesota. One of these groups was sent forward to Nashville. It consisted of 59 men led by Sergeant Henry Kelsey, who had served his three years, had been discharged, and, apparently tiring of civilian life, had re-enlisted.

The detachment would go no further than Nashville until the following spring. On November 15, 1864 Sherman destroyed the Western & Atlantic Railroad between Dalton, Georgia and Atlanta, cutting himself off from the outside world. His army, including the 2nd Minnesota, then began its three hundred mile march across Georgia to the sea.

Cruft’s Division, Provisional Detachment of the District of Etowah.

The 2nd Minnesota contingent in Nashville was not alone. Scattered between Nashville and Chattanooga were a large number of soldiers from Sherman’s army. Some were new recruits, many of them draftees or substitutes of dubious reliability and all with little or no training. Others were returning convalescents. Others still were coming back from furlough. Some were detailed men such as commissaries, quartermasters, guards — REMF’s in modern military jargon – who were no longer needed once the units they supported cut their ties with their Tennessee bases. And some, like the U. S. Colored Troops maintaining and guarding the rail lines and supply depots around Nashville and Chattanooga, had been displaced as the result of the Confederate advance into Middle Tennessee. As Hood’s Tennessee Campaign developed the Union Army viewed these men and units as a manpower resource.

On November 25 General Thomas ordered Brigadier General Charles Cruft to organize casuals from the XIV, XV, XVII, and XX Army Corps then within the department into four brigades. Sergeant Kelsey’s detachment was thrown into a XIV Corps brigade. These units were attached to the Provisional Detachment of the District of Etowah, itself an ad hoc formation commanded by Major General James B. Steedman. The Provisional Detachment also included two brigades of United States Colored Troops.

Steedman’s troops were placed on the leftmost part of the Federal lines around Nashville, covering the area from Nolensville Pike to Lebanon Pike. Between December 1 and December 11 the two Colored Brigades conducted a number of reconnaissances out Murfreesboro Pike to the Confederate right flank in the vicinity of a residence called the Rains house (not to be confused with another Rains house at the current site of the WNPT television studios located, logically enough, on Rains Avenue) close to the Nashville & Chattanooga railroad line. These were probably intended as toughening exercises for these untested brigades.

Attack on the Confederate Right, December 15, Federal Organization

This was how things stood when General Thomas issued his attack order late in the afternoon of December 14. As part of that attack, one of the two ad hoc brigades from the XIV Corps and the 1st Colored Brigade were to make a diversionary attack on the Confederate right wing, which was thought to rest on the line of the Nashville & Chattanooga Railroad. The idea was that this attack would draw off troops from the Confederate left, which was to be the focus of the Federals’ main assault. The attacking element consisted of these units:

The 1st Colored Brigade, commanded by Colonel Thomas J. Morgan who was also in overall command of the operation. It was composed of the following units:

- 14th U. S. Colored Troops, 610 officers and men. Lieutenant Colonel Henry C. Corbin, commanding. Raised in Gallatin, Tennessee, the Fourteenth had been stationed in Chattanooga performing guard duty. Morgan had previously been colonel of this regiment, and there was bad blood between Morgan and Corbin.

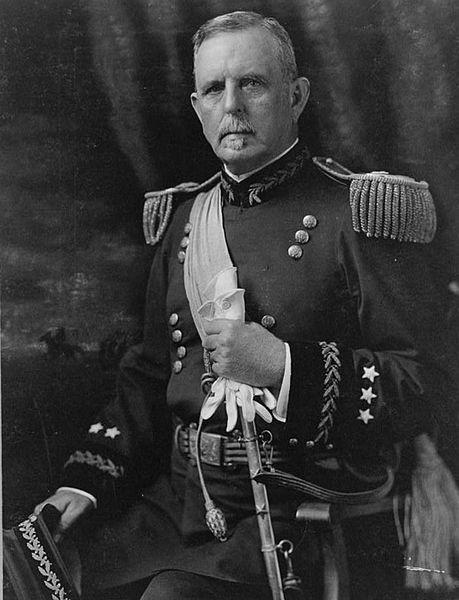

Above:: Henry C. Corbin took command of the 14th U. S. Colored Troops at the Battle of Nashville when its Colonel, Thomas J. Morgan, was placed in temporary command of the 1st Colored Brigade. Colonel Morgan stated in his report of the Nashville battle that Corbin “does not possess sufficient courage to command brave men.” Corbin was subsequently tried before a general court martial on the charges of cowardice and misbehavior in the presence of the enemy. The court martial transcript makes it abundantly clear that it was the last step in a vendetta between the two men. Corbin was found not guilty and “was most honorably acquitted” by the court martial; the court martial specifically condemned two of Morgan’s witnesses for “misrepresentation” and Morgan himself for coaching witnesses. Corbin continued to serve in the postwar Army, rising to the rank of Lieutenant General. This photograph was taken in the 1890’s when he was Adjutant General of the United States Army. Library of Congress.

- 17th U. S. Colored Troops, commanded by Colonel William Shafter, somewhere in the area of 600 officers and men. It had been raised in Murfreesboro and had previously served as commissary guards in Nashville, probably doing more warehouse work than actual guarding. The 17th came to the 1st Colored Brigade more or less by accident. The 16th U. S. Colored Troops (which had been part of the Chattanooga garrison) was initially assigned to the 1st Brigade. On the evening of December 14, 1864 the commander of the 16th wrangled a transfer from this brigade to the army’s pontoon bridge train. Morgan, who apparently had a problem getting along with subordinates, described this transfer as an “unsoldierly process” and demanded a court of inquiry which subsequently cleared the 16th’s colonel of any misfeasance. Colonel Shafter volunteered his regiment to take the place of the 16th, and so the 17th was assigned to the 1st Colored Brigade.

Above: William R. Shafter served in various Michigan regiments before he was made Colonel of the 17th U. S. Colored Troops, and indeed was awarded the Medal of Honor for his conduct at the Battle of Fair Oaks/Seven Pines in 1862. The award was made in the 1890’s when Shafter was a senior officer, so it may be somewhat questionable. Shafter served in the army after the war, commanding African-American units in the Indian Wars, and acquired the nickname “Pecos Bill”. He was promoted to Major General and commanded the American expedition to Cuba during the Spanish–American War. This photograph shows him as a civilian following his retirement in 1901. Public domain.

- 18th U. S. Colored Troops, 363 officers and men, commanded by Major Lewis D. Joy. This unit had been raised in Missouri September, 1864 and was sent to Nashville in late November.

- Two or three companies from the 44th U. S. Colored Troops, commanded by Colonel Lewis Johnson, 212 officers and men. This was composed of men from Chattanooga. The bulk of this regiment had been captured when the garrison at Dalton, Georgia had surrendered to Hood’s men on October 13, 1864.

3rd Brigade (XIV Corps). Lieutenant Colonel Charles H. Grosvenor commanded this formation, which included the following organizations:

Above: Charles H. Grosvenor enlisted in the 18th Ohio Infantry in 1861 as a private. He was soon elected as major and served with the regiment through its major actions at Stones River, Chickamauga, Missionary Ridge, and the Atlanta Campaign. In 1863 he was made a lieutenant colonel. He assumed command when the regiment reorganized in October, 1864, and was made commander of an ad hoc three regiment brigade when the regiment was attached to Steedman’s Provisional division at the time of the Battle of Nashville. Postwar, he was active in state and national politics. He represented southeastern Ohio as a Republican for ten terms in Congress in the between 1885 and 1907. He died in 1917 and is buried in Athens, Ohio. Public domain.

- 18th Ohio Veteran Volunteer Infantry. This unusual unit consisted of 325 officers and men commanded by Captain Ebenezer Grosvenor. Ebenezer was Charles Grosvenor’s brother. He had succeeded Charles in command of the regiment when Charles assumed command of the brigade. The Eighteenth Ohio Volunteer Infantry was an 1861 unit which did not veteranize and had mustered out on November 9. On October 31, though, a new unit – the Eighteenth Ohio Veteran Volunteer Infantry – came into being. It was composed of soldiers from five other Ohio regiments that had not veteranized: the 1st Ohio, the 2nd Ohio, the 18th Ohio, the 24th Ohio, and the 35th Ohio. Some of these soldiers had chosen to re-enlist, and others were soldiers whose terms of enlistment had not yet expired.

- 68th Indiana Infantry, 255 officers and men. Lieutenant Colonel Harvey J. Espy, commanding. This regiment was raised in August, 1862. It was captured at Munfordville, Kentucky in September, 1862, was exchanged, and went on to fight at Chickamauga and at Missionary Ridge. Afterwards it served as part of the Chattanooga garrison. Its original term of service had not expired.

- 2nd Battalion, XIV Army Corps, 319 officers and men. Captain D. H. Henderson, 121st Ohio Infantry, commanding. Captain Henderson had been severely wounded while serving with his regiment at Jonesboro in late August. His command was a pick up unit formed from casual troops nominally assigned to the XIV Army Corps of the Army of Georgia. It included Sgt. Kelsey’s 59 recruits from the 2nd Minnesota. A similar unit of XX Corps troops was described this way:

“Quite a large proportion of the men thus designated as effective were, in fact, quite unfit for duty in the field – many were still suffering from wounds sustained in the Georgia campaign; others were fresh from the hospitals and only partly convalescent from the effects of sickness; while a still larger number were raw recruits, utterly uninstructed and not inured to hardship. The recruits represented almost every European nationality, and very many of them were unable to speak or understand the simplest words of our language.”

- 20th Battery, Indiana Light Artillery, 135 officers and men. Captain Milton A. Osborne, commanding. The battery was another unit raised in the summer of 1862. For most of the war this battery had served in rear echelon garrisons with its only battle experience being in the Atlanta campaign.

Above: In 1865 the Engineer Department of the Army of the Cumberland made a topographical map of the Nashville battlefield. Since it dates from the time of the battle it probably is an accurate depiction of the field works and fortifications present around Nashville at the time of the battle. The engineers did not take magnetic declination into account so the map is oriented a little west of true north. On the map Granbury’s Lunette is shown immediately to the northeast of the railroad line. Keep in mind that this is a map symbol and does not necessarily show the shape or exact orientation of the earthwork. The Union trench lines shown around the Lunette were probably constructed by Federal forces on December 15 after repulse of the initial attack. The country lane running between Murfreesboro Pike and Nolensville Pike is now Foster Avenue and Glenrose Avenue. The attack of the 1st Colored Brigade aligned on its left on Foster Avenue. Grosvenor’s Brigade initially was in the right rear of the 1st Colored Brigade but made a quarter turn to attack the Lunette directly. Public Domain, enlargement made by John B. Allyn.

A Bit of Railroad History

Around 1914 the Louisville & Nashville Railroad built a cutoff line that bypassed the congested yards in downtown Nashville. This ran from Amqui Junction in Madison to the then new Radnor Yards in South Nashville. The high bridge across the Cumberland in Shelby Park is part of the cutoff, and Radnor Lake was created to provide a water supply for the new yards.

In order to get to the Radnor Yards, the L&N had to cross its subsidiary, the former Nashville & Chattanooga. The N & C is the rail line that existed at the time of the battle and it passes through a deep cut at Rains’ Hill. Heavy traffic made it undesirable for the two busy main lines to cross at grade so the new line passed above the Chattanooga line on the southeastern slope of Rains’ Hill. The Chattanooga line was lowered 5 – 10 feet so that trains passing under the new cutoff would have sufficient clearance. The floor of the cut was lowered again in the 1980’s or 1990’s when extra-tall double stack trains were introduced.

Thus, the cut that we see today is both deeper and longer than its 1864 forebear. While the 1864 cut was still a forbidding obstacle, positions on the north side of the cut could be readily accessed from the rest of the Confederate line by crossing the railroad at the north or south entrances to the cut. By the same token, Federal attackers coming from Murfreesboro Pike could cross the railroad at either end of the cut, though the linear formations of the day would likely be disrupted when the attackers advanced down, up, and over the cut.

Above: This looks northwest (towards downtown Nashville) from the Polk Avenue railroad overpass. Note that today the cut comes to an end about 350 yards from the overpass; based on the 1864 map above the cut ended about 100 yards from this point. While the cut was an obstacle to an attack, individuals could go back and forth across the tracks without too much of a problem. Photograph by John B. Allyn.

Above: This photograph was taken at the northwest end of the cut, 350 yards from the Polk Avenue overpass. The end of the cut in 1864 would have appeared similar except for the second track. This shows that the track is passable by a man on foot or on horseback. However, it would be quite an obstacle for a Civil War military unit advancing in the usual linear formation. Photograph by John B. Allyn.

The Confederate Right Flank – Confederate Organization.

Confederate troop dispositions on the right flank are hard to determine since few of the Confederate commanders involved submitted reports on the Nashville battle. What we do know comes from the few reports that were made, some contemporary letters, and memoirists writing years after the war.

Above: Major General Benjamin F. Cheatham. Cheatham was a native of Nashville who had served in the Mexican War and was a brigadier general in the Tennessee militia at the time of Tennessee’s secession. He entered the Confederate Army at the same rank and served in all of the battles of the Army of Tennessee from Belmont to Nashville. He was made corps commander in the early fall of 1864 when William J. Hardee, a critic of John Bell Hood, asked to be reassigned. Cheatham had a reputation for hard drinking and hard fighting. Hood considered him at fault for his failure to bag Schofield’s army at Spring Hill. He was still under a cloud at the Battle of Nashville, notwithstanding the near-destruction of his Corps at Franklin, that time done in strict obedience to Hood’s orders. After the war he married and returned to running the family plantation, Westover. Oddly, he was a warm friend of Ulysses S. Grant. He died of a heart condition in 1886, survived by his wife and five children, one of whom went on to become a Major General in the United States Army in the period between the two World Wars. Library of Congress.

The eastern end of the Confederate line was manned by Cheatham’s Corps. As of December 15, Bate’s Division was on the Corps’ western flank, with its lines running west from Nolensville Pike to the eastern flank of Lee’s Corps. On Bate’s right were Brown’s Division (commanded by Mark Lowrey) and Cleburne’s Division (commanded by James A. Smith) which together extended the Confederate line from Nolensville Pike to the railroad.

Above: Brigadier General James A. Smith. Smith was born in Tennessee and graduated from West Point in the Class of 1853 along with John A. Schofield and John Bell Hood. He left the Army when Tennessee seceded, and was given a commission as a lieutenant in the Confederate Army. In 1864 he commanded a brigade of Georgians in Cleburne’s Division, and succeeded to command of the Division when Cleburne was killed at Franklin. Smith moved to Mississippi after the war and engaged in farming, interspersed with various political appointments at the state and national level. He died in 1901. Public domain.

Above: Captain E. T. Broughton. Edward T. Broughton Jr. was born in Alabama in 1834. He came to Texas with his family in 1847 and was admitted to the bar ten years later. When Texas seceded in 1861 he joined the Confederate Army and was elected Captain of Company C of what became the 7th Texas Infantry. The 7th Texas was captured at Fort Donelson in February, 1862 and Broughton was sent to Johnson’s Island in Ohio. He and his regiment were exchanged that fall. The 7th Texas was assigned to Gregg’s Brigade in Mississippi and was part of the Port Hudson garrison. When Grant crossed the Mississippi Gregg’s Brigade was sent north to join with Joseph Johnston’s command in the central part of the state. En route they encountered McPherson’s XVII Corps at Raymond,, Mississippi. Broughton was captured in the ensuing battle and was sent again to Johnson’s Island. He contracted smallpox there which caused him to go partially blind. He was exchanged again in May, 1864, probably on the basis of disability. He rejoined his regiment in North Georgia and participated in the Atlanta Campaign. General Granbury, who succeeded Gregg as brigade commander, promised to promote him to Lieutenant Colonel, but this was never acted on officially. Broughton took command of the brigade after Granbury was killed at Franklin. In early 1865 he resigned his commission based on illness, and returned to his family in Texas. He was active in politics after the war. He died in 1874 from the effects of the illnesses he contracted on Johnson’s Island. Public domain.

On December 13 Granbury’s Brigade, the reserve brigade for Cleburne’s Division, was directed to build a four gun lunette on a wooded hilltop just on the northeast side of the railroad. This was completed the next day. A lunette is an open-ended field fortification which is used as an artillery position. A lunette is shaped in such a way that the guns can provide support on both its front and flanks. Granbury’s Brigade manned the lunette and set out skirmishers on a ridge parallel to the railroad. The brigade then amounted to 344 men and was commanded by Captain E. T. Broughton, formerly of the 7th Texas Infantry. This was a small brigade even by Confederate standards. Goldthwaite’s Alabama Battery of four guns was also placed in the Lunette.

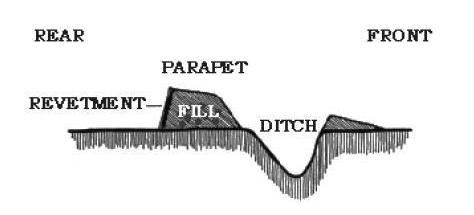

A Brief Discourse on Field Fortifications

Above: This view looks to the north on Polk Avenue from its intersection with Fiber Glass Road. The northwest face of the Lunette can be seen just beyond the single storey commercial structure on the right hand side of the road. The railroad passes under Polk Avenue just beyond the remains of the Lunette – the guard rails on the overpass can be seen on the right side of the road. In 1864 the Lunette extended up to and across the crest of the ridge just beyond the overpass. The rail line is a connector between the CSX Chattanooga line and the CSX cutoff between Amqui Junction and the Radnor Yards. Its construction in 1914 destroyed most of the Lunette. Photograph by John B. Allyn.

The northwestern face of Granbury’s Lunette still exists. It is on Polk Avenue about 100 yards north of the highway overpass over the CSX main line to Chattanooga. The work faced to the north and had a good command of Murfreesboro Pike. At the time the Radnor cutoff was constructed a connector was built from the Nashville & Chattanooga line to the new line. The connector reached the Radnor line through a deep cut. Construction of this cut resulted in the destruction of a large part of Granbury’s Lunette.

As noted above, the Lunette was built in a two day period immediately before the battle. The return of Bate’s Division from Murfreesboro enabled the Confederates to extend their right flank across the railroad. The two Colored Brigades had been skirmishing with the Confederates in the areas north and east of railroad line in the week preceding Bate’s return. Construction of the Lunette allowed the Confederates to observe activity on Murfreesboro Pike (a low ridge masked the Pike from observers on the railroad line) and provide better flank protection.

Above: A cross section of a Civil War field fortification similar to Granbury’s Lunette.

By this stage of the war, the Confederates (and their Federal counterparts) were quite skilled at quickly building field fortifications.

The first step was to lay a line of fill – logs, fence rails, or stones – along the intended line. Given the twin facts that the Lunette was being built next to the railroad and that the Confederates were skilled railroad wreckers, it is likely that some of this fill consisted of railroad rails and ties.

A ditch was then dug around the perimeter with the spoil thrown on top of the fill. Lumber – usually from a convenient house or barn – was used to make the revetment, an interior retaining wall supporting the parapet. Lumber was also used to create gun platforms within the fortification, an important consideration at Nashville, where mud was a serious problem. Again, it is likely that the Confederates used railroad ties for their revetments and platforms; the Rains house, about 200 yards away and doubtless a good source of lumber, was sufficiently intact to serve as a Union strongpoint in the upcoming battle.

The Confederates completed the fortification by placing a palisade of sharpened tree trunks and limbs on the outer side of the ditch.

Above: This is a closer view of the northwestern face of Granbury’s Lunette. The walkway goes down the middle of the outside ditch. There is a low rise to the left of the walkway which is the remains of the outside of the ditch. Sharpened tree trunks and tree limbs would have been implanted here to impede any advance across the ditch. Photograph by John B. Allyn.

Morgan’s Command Advances.

Thomas ordered Steedman to make a “heavy demonstration” on the Confederate right. In turn, Steedman ordered Morgan to “strongly menace” the Confederate right. The goal was to make the Confederates send reinforcements to their right from Stewart’s Corps on their left, where the main attack was to be made later or, barring that, to deter the Confederates from detaching troops from their right to send to the embattled left. In other words, this was clearly intended as a diversion; Morgan’s command was not expected to drive in the Confederate right though if that occurred no one would complain.

Morgan’s command was encamped in a line of trenches running from Murfreesboro Pike to Lebanon Pike in the general vicinity of today’s Napier Homes. Morgan’s orders were to move out on Murfreesboro Pike at daylight until they came even with the Confederate right flank. The attacking force then would then face to its right and form in two lines of battle. The 1st Colored Brigade would advance on the left, with Grosvenor’s brigade advancing to the right and in the rear of 1st Colored Brigade. The two brigades began their advance at 7 am on December 15. It was very foggy that morning, which slowed the speed of the advance.

Morgan had conducted a reconnaissance in the early morning hours of the fifteenth. He observed a line of picket campfires on a low ridge east of and roughly parallel to the railroad line. He also observed what he thought was a curtain wall – something like a frontier stockade – on the east side of the railroad at the end of the Confederate picket line. This was not a curtain wall, but instead was the palisade of the Lunette, a much more formidable obstacle. Given the fact that the Lunette had just been built and that he was conducting a reconnaissance in the middle of the night (albeit with a near full moon) his mischaracterization of the Lunette is probably forgivable. The ridge blocked his view of the railroad line itself and he seems to have been unaware of the existence of the cut.

The two brigades had marched about two miles by 10 am when they reached the point of departure on Murfreesboro Pike. Morgan placed the 68th Indiana, the 18th U. S. Colored Troops, and a three gun section of the 20th Indiana Battery on his left flank to protect against any counterattack from that direction by the Confederates.

The main assault consisted of the 14th U. S. Colored Troops acting as skirmishers followed by the main line of battle composed of the 17th U. S. Colored Troops on the right and the 44th U. S. Colored Troops on the left.

Above: This photograph looks north on Foster Avenue from the railroad overpass. In 1864 this was a country lane, and the 1st Colored Brigade used it to align its left flank. The Confederate skirmish line ran along the ridge in the background, and after it was driven in a three gun section of the 20th Indiana Battery deployed to the ridge on the right side of the photograph. Granbury’s Lunette was at the northwest end of this ridge about 600 yards to the left, out of the photograph, and would have had the 1st Colored Brigade enfiladed throughout its advance. Confederate reinforcements on the southwest side of the tracks (behind the photographer) would not have been able to see the brigade until they came over the ridge. Photograph by John Allyn.

Above: This is a view along Foster Avenue looking to the south from the crest of the ridge. The 20th Indiana Battery would have deployed near here. The 1st Colored Brigade advanced down the slope towards the railroad in the middle distance – note the Foster Avenue overpass. This would have been a crossing at grade in 1864. The Confederate reserve brigades would have been formed somewhere between the ridge in the far distance and the railroad line. At this point the 1st Colored Brigade would have come under fire from the six guns south of the railroad as well as the enfilading fire from Granbury’s Lunette to the east.

A three gun section from the 20th Indiana Battery was also on the left. It was initially posted on Murfreesboro Pike, but after the brigade advanced past the Confederate picket line the battery was advanced to the low ridge where the picket line had been. This would be on what is now the campus of the Nashville School of the Arts (formerly the Tennessee Preparatory School) on Foster Avenue. This section could fire on the Lunette and also on any counterattack coming from across the railroad line. The other section was placed in front of the Catholic Orphans Asylum northeast of the Lunette. This was located on what is now the campus of Trevecca Nazarene University.

Both sections of the battery opened a spirited barrage on the Confederate flank. During the course of the day the battery would expend 624 rounds of ammunition, or over 100 rounds per gun.

Above: This looks northwest (towards downtown Nashville) from the Foster Avenue overpass. The line was only single track in 1864, and the siding going off to the left did not exist. Troops from the 14th U. S. Colored Troops advanced from right to left across this track and were almost immediately repulsed by Confederate reserves.

The line of advance was such that the men and guns in Granbury’s Lunette – on the same ridge as the picket line — perfectly enfiladed the attackers. In addition, Cheatham placed his infantry reserves and one or two artillery batteries at or near the south side of the railroad line.

Identifying these units is problematic. From various sources:

- James A. Smith’s report briefly addresses that assault. He only mentions Granbury’s Brigade in connection with the repulse.

- However, a contemporary account from a member of Granbury’s Brigade puts Goldthwaite’s Alabama Battery (four guns) in the Lunette and Key’s Arkansas Battery (four guns) on the far side of the cut. Both were part of the artillery battalion supporting Cleburne’s Division.

- In his report of the campaign Bate says that his division was inactive during the day of the fifteenth. However, several postwar accounts place Jackson’s Brigade of Bate’s Division at the cut along with the remaining two guns (the other two were captured at Third Murfreesboro) of Slocomb’s Louisiana Battery. Jackson made no separate report.

- Another postwar account places Maney’s Brigade of Brown’s Division at the cut. Mark Lowrey, commanding Brown’s division, made no report after the battle, nor did Hume R. Feild, commanding Maney’s Brigade.

- By way of explanation, these two brigades may have been the reserve brigades for their respective divisions and were in a position to move to a threatened point.

- While exact numbers are still unclear there nonetheless was a fairly formidable force facing the 1st Colored Brigade.

After the 1st Colored Brigade overran the light Confederate skirmish line, they passed the Lunette on their right which continued its enfilading fire. They also came under fire from the six guns on the far side of the railroad.

The advance of the 17th U. S. Colored Troops came to a halt as they approached the railroad cut, which was impassable to their front. At that time they were under heavy fire from their front and flank. Shafter called on Morgan for reinforcements and tried to realign his regiment to its right to attack the Lunette. This would have been a difficult maneuver even for experienced troops, and the 17th was not experienced. The result was that the 17th fell apart and retreated in what Shafter described as a “rather disorderly manner.” Before it retreated the 17th sustained casualties of 2 officers and 14 men killed, and 4 officers and 64 men wounded. This was about 15% of the 600 or so engaged. The regiment reformed on Murfreesboro Pike.

The 44th U. S. Colored Troops were to the left of the 17th. Their casualties – 4 men wounded – were very low, suggesting that they retreated sooner and faster than their neighbors in the 17th did.

The 14th U. C. Colored Troops made up the brigade skirmish line. They advanced across the railroad at a point beyond the end of the cut. This force was counterattacked by Cheatham’s reserves and quickly driven back with heavy losses: .4 men killed, 41 men wounded, and 20 men missing. Presumably the missing men were taken prisoner.

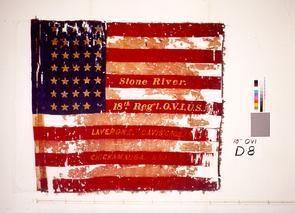

Above: Flag of the 18th Ohio Veteran Volunteer Infantry Regiment. This regiment was raised in southeastern Ohio in 1861. The regiment did not veteranize when the unit’s three year term of service expired in October, 1864. The men who did reenlist were joined by reenlistees from four other Ohio regiments. The unit the sustained heavy casualties in what turned out to be a one regiment assault on Granbury’s Lunette on December 15, 1864. Used with permission, Glenn Davis, 18th Ohio VVI website, http://www.18thovi.com.

Grosvenor’s Brigade Attacks the Lunette.

Grosvenor’s Brigade was formed in the right rear of the 1st Colored Brigade with the 2nd Battalion, XIV Army Corps on the left and the 18th Ohio on the right. A low knoll to their right front screened them from fire from the Lunette. Up to this point they had not received an order to advance.

After hearing from Shafter, Morgan belatedly went to Grosvenor and directed him to assault the works in his front, pointing to the Lunette which was partially hidden in a grove of trees at the top of a rise. Grosvenor’s men advanced across open fields towards the Lunette. During their approach they were under fire from the guns in the Lunette which, given the impending collapse of the 1st Colored Brigade, were now free to focus their exclusive attention on Grosvenor’s advance.

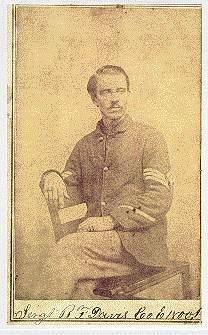

Above: Sergeant Benjamin F. Davis of the 18th Ohio Veteran Volunteer Infantry. Davis was born in 1840 in Belleville, Virginia (now West Virginia) and moved to Ohio at an early age. He enlisted in the 18th Ohio in 1861 and participated in all of its actions in the western war. He was wounded at Chickamauga. He re-enlisted when the regiment’s term of service was up in October, 1864 and served as commander of Company A of the consolidated regiment at the Battle of Nashville, where he was commended in his commander’s report. He was subsequently promoted to second lieutenant. Following the war he moved with his new wife to Missouri and then to Kansas. He died in Morrill, Kansas in October, 1919. When he died his active pallbearers were all young veterans of what was then quaintly called The Great War. He was survived by his widow, seven children, seventeen grandchildren, and nine great grandchildren. Used by permission from Ms. Diana Roche, Sergeant Davis’ descendant.

Concentrated fire notwithstanding, the 18th Ohio struck the front face of the Lunette. The regiment claimed that over 100 of its men gained the interior of the work but there is considerable reason to doubt this. Captain Grosvenor – the regimental commander, not the brigade commander — was killed while trying to go over the walls of the Lunette. Another officer, Lieutenant Samuel W. Thomas, was killed close by as he tried to tear down the palisades outside the Lunette. Captain John Benedict, who succeeded Grosvenor in command, was temporarily incapacitated almost immediately afterwards when a spent bullet hit his knee. He was about forty yards outside the work when this occurred. He was succeeded in command by Lieutenant Charles Grant. In an era when officers led from the front, all of these officer casualties were outside the fort, so it would appear that the 18th Ohio got no further than the palisade and the ditch. Smith specifically states in his report that Granbury’s Brigade sustained minimal casualties in the assault which further supports this conclusion.

The 2nd Battalion, XIV Army Corps, including the contingent from the 2nd Minnesota, advanced on the left of the 18th Ohio. It came under the same heavy fire and began wavering. Lieutenant Colonel Grosvenor, who personally led them, dismissed them as “mostly new conscripts, convalescents, and bounty jumpers.”

As soon as these troops came under fire they began to hesitate and waver. The Confederates took note of this and gave the 2nd Battalion a very heavy musket volley which severely wounded the nominal battalion commander, Captain Henderson of the 121st Ohio and inflicted very heavy casualties — 1 officer and 19 men killed, 3 officers and 74 men wounded, and 33 men missing (most of these were likely deserters, given the makeup of the battalion, and not true combat casualties), about 30% of the battalion’s strength not counting the missing. The rest of the battalion, including the entire detachment from the 2nd Minnesota, then fled to the rear. Grosvenor bluntly stated that they behaved “in the most cowardly and disgraceful manner.” The Confederates were then free to direct all of their fire on the 18th Ohio which was driven away from the Lunette. The fighting in front of and on the Lunette lasted no more than ten to fifteen minutes. In the brief fight the 18th Ohio sustained serious casualties: 2 officers and 9 men killed, 2 officers and 38 men wounded, and 9 men missing, almost 20% of the unit’s strength.

The Fight Continues

At this point it was almost noon. Steedman arrived on the scene and ordered Morgan to move his force to the north and west of the Lunette

The 18th Ohio plus whatever could be herded together from the 2nd Battalion reformed and were joined by the 68th Indiana. Grosvenor’s brigade aligned on the railroad so that it adjoined the 2nd Colored Brigade. A Confederate battery to the west of the railroad was harassing the 2nd Colored Brigade, and Grosvenor was directed to advance a heavy skirmish line to the Rains house (near the present-day location of Hayes Pipe Supply on Fiber Glass Road) which stood about 200 yards northwest of the Lunette. The house was loopholed for sharpshooters.

The 1st Colored Brigade formed on Grosvenor’s left. The section of the 20th Indiana Battery that had been on the left joined the other section in front of the Catholic Orphan Asylum.

Sharpshooters from the three brigades and the guns of the Indiana battery kept up a desultory fire for the remainder of the day. This fire was returned in kind, with the result that the Rains house and the Asylum were destroyed by Confederate artillery. Eventually the Confederate batteries ceased firing, probably because they were under an order to conserve ammunition. Granbury’s Brigade had not sustained many casualties up to this point but the sniping and shelling steadily eroded the Brigade’s strength. It ultimately sustained about 30 casualties, approximately 10% of its strength, and almost all of these casualties were sustained in this last phase of the battle. Among the wounded was Captain Broughton, and he was succeeded by Captain James Selkirk, commander of the 6th/15th Texas Infantry.

After sunset Cheatham’s Corps was withdrawn to the south where on the next day Brown’s (Lowrey’s) and Bate’s Divisions would defend Shy’s Hill. The withdrawal was skillfully done, and Steedman’s Federals did not realize that the Confederates had gone until the next morning. Steedman’s men went out Nolensville Pike that morning. Later in the day they participated in the abortive assault on Peach Orchard Hill.

The Minnesotans Connect With Their Regiment

On April 9, 1865 Sergeant Kelsey and his 59 recruits joined the 2nd Minnesota Veteran Volunteer Infantry near Goldsboro, North Carolina. They had travelled by train and steamboat from Nashville to the Chesapeake Bay, and had gone from there by ocean steamer to North Carolina. The regimental historian noted proudly that none of the recruits had deserted during their long trek across the eastern United States. They saw no further combat, and participated in the grand review of Sherman’s Army in Washington. The regiment returned to Minnesota, and everyone was discharged in St. Paul in July, 1865.

Summary

Morgan’s assault had lasted less than two hours from the time the first troops stepped off from Murfreesboro Pike to the time the last soldier retreated back to the original line of departure. The attack did not accomplish what Thomas had hoped: Hood did not move any troops from his left in response to the attack, and reinforced his left from Lee’s Corps. Cheatham did not send any troops from his corps to the left until after sundown. By that time the Confederate left had completely collapsed.

Approximately 350 of Morgan’s force were casualties – killed, wounded, or missing – out of the 2,800 or so engaged. This was around 12% of the total, hardly a bloodbath by Civil War standards. This was probably a reflection on the rapid collapse of the attack and the speed of the retreat. The attack was poorly planned and poorly executed. With the notable exception of the 18th Ohio Infantry, it was carried out by troops who were only partially trained and, in the case of the 2nd Battalion, XIV Army Corps, poorly motivated. The Confederate troops, on the other hand, were well entrenched and well-trained. The result was inevitable.