The Fall of the Redoubts

On December 2, 1864, Gen. John Bell Hood brought his war-weary troops to Nashville, following their withering frontal attack at Franklin, Tennessee on November 30.

His army, then numbering about 25,000, was positioned south of Nashville with its right flank aligned along present day Woodmont Boulevard. At the roadway that was then — as it is now — Hillsboro Pike, the line turned sharply to the south (a “refused line”) and ran generally parallel to the Pike. To support this thin line, Hood ordered the construction of five log-and-earthen forts called redoubts.

Three of these — Redoubts 1, 2 and 3 — were clustered in a relatively confined area near what is now the intersection of Woodmont Boulevard and Hillsboro Road. The other two – No. 4 and 5 — were positioned slightly more than one mile to the southwest.

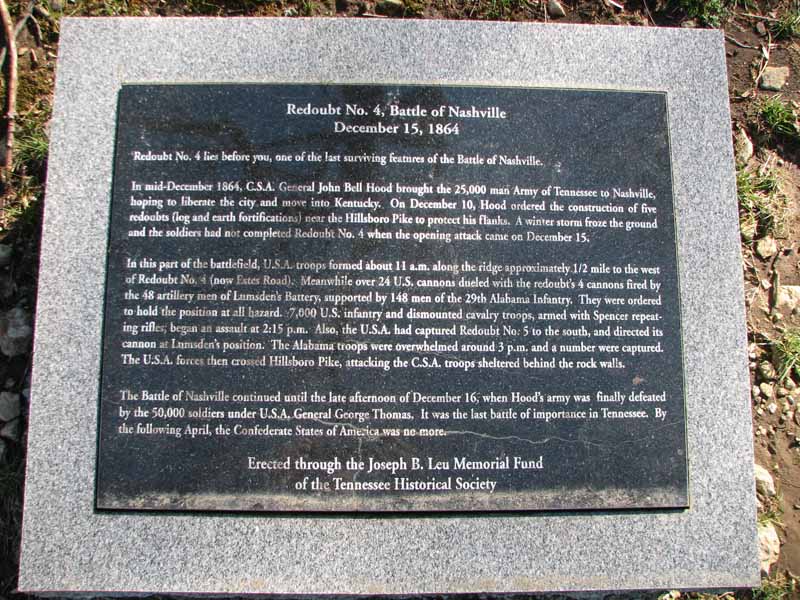

Interpretative monument at Redoubt No. 4 erected by the Tennessee Historical Society. Click to enlarge.

Of these five Redoubts, the remnants of only three are still in existence. The Battle of Nashville Preservation Society has purchased and preserved Redoubt No. 1 off Benham Avenue, and the barely visible remains of Redoubt No. 3 are perceptible on the high ground now occupied by Calvary Methodist Church on the west side of Hillsboro Road.

The two photos above show the remains of Redoubt 4’s earthen wall which faces north (to the left of this view) and the city of Nashville. The Hillsboro Pike is approximately one-half mile to the east. (Photos by Todd Lawrence)

Portions of the north wall of the last remaining redoubt, No. 4, can be seen at the top of a hill in the gated residential community of Abbotsford in South Nashville. On this high ground, Lumsden’s Battery consisting of 48 men and four smoothbore Napoleon cannons, and supported by about 100 men from the 29th Alabama Regiment from Walthall’s command, defended the unfinished earthwork for several hours on December 15, 1864, the first day of the battle.

They were shelled constantly for most of that time from the west by Federal artillery which was positioned along a line where Estes Road is currently located. Shortly after 2 o’clock in the afternoon, Redoubt No. 4 was overrun by attacking Federal ground troops, followed shortly thereafter by Redoubt No. 5 (which has been destroyed by residential development), allowing the surge of Federal forces attacking in a huge wheeling motion from the northwest to advance and begin to overrun the Confederate line near the Hillsboro Pike. The other three redoubts fell shortly thereafter.

It is worth noting that historical accounts of this phase of the Battle of Nashville disagree as to which of the two southern-most redoubts, Nos. 4 and 5, fell first. The venerable book by Stanley F. Horn, The Decisive Battle of Nashville (1956), as well as the Tennessee Historical Society’s engraved summary on its Redoubt No. 4 monument (see photo above), show No. 5 falling first. James Lee McDonough, in a more recent book, Nashville: The Western Confederacy’s Final Gamble (2004), interprets field reports as showing No. 4 falling first. Taking a general overview of the battle, this is a minor debate, considering the fact that thousands of Federal troops overwhelmed the few hundred Confederates holding these two fortifications within just minutes of each other.

The view of the two photos above is westerly toward present day Estes Road, where 24 U.S. cannons pounded the Redoubt from approximately 11:00 a.m. to 2:15 p.m. on December 15, 1864. (Photos by Todd Lawrence)

At the time of the December 15 battle, extremely harsh winter conditions had prevented completion of the Redoubt No. 4. Even now, however, more than 150 years later, the massive amount of work accomplished by hand in frozen ground is plainly visible at this small remaining portion of the Redoubt. The site has been preserved by the Tennessee Historical Society, which has placed an interpretive monument at the base of the north face of the earthen wall, located at the south end of Foster Hill Road.

The two photos above show the view looking in a southerly direction up the elevated north face of the Redoubt. (Photos by Todd Lawrence)

September, 2021

KAY DESCRIBES THE RISE AND FALL OF REDOUBT NO. 4 IN A PRESENTATION TO ABBOTTSFORD RESIDENTS WHOSE PROPERTY ENCOMPASSES THE PRESERVED FORT

Jim Kay, president of the Battle of Nashville Trust, spoke by invitation on Saturday, Sept. 18, 2021, to the residents of the Abbottsford community about Redoubt No. 4, the historic remnants of which have been partially preserved on their property.

Abbottsford Relics on display. All the artillery shells and friction primers were found at the site.

From his huge collection of Civil War artifacts which he has been discovering in Nashville neighborhoods since childhood, Kay brought and displayed many that were found in the vicinity of Redoubt No. 4 at Abbottsford, which had previously been the farm of Frank R. Leu.

He began his presentation with an overview of the city of Nashville under Federal control, noting that the massive battlefield area south of Fort Negley had been largely denuded of trees, not only for firewood, but also for clearing a “field of fire” for artillery. That included the hills where Redoubts 4 and 5 were located, west of the Hillsboro Pike. As he noted, Confederate forces on this very high ground could see for many miles, and conversely, Union forces could see the Confederate works.

Redoubt No. 4 was involved in some of the earliest and heaviest fighting on the first day of the battle, December 15, 1864. The Redoubt itself was an earthen fort which Confederate troops began digging on December 2, 1864, after Gen. John Bell Hood brought his army north from Franklin. Due to harsh winter conditions, excavation was extremely difficult, and construction was not completed before the battle. Kay said the Redoubt would have been laid out by Maj. Wilbur Foster, a military engineer assigned to Gen. A.P. Stewart’s corp. Today, the high ground where the remnants of the Redoubt are located is named “Foster Hill,“ possibly after Major Foster, though some sources believe it is named for the chaplain of the 29th Alabama Regiment.

The fort consisted of 8-foot compacted dirt walls, strengthened by cut trees. Inside the walls were four 12- pounder Napoleon smoothbore cannons, each operated by a crew of about10 artillerymen. The cannons were spaced about 12 -14 yards apart, and faced outward through embrasure openings in the walls. About 35 yards to each side of the cannon emplacements, in a 3-foot deep trench-line, were about 125 support troops from the 29th Alabama.

The unit was commanded by Capt. Charles Lumsden, a graduate of Virginia Military Institute and previously head of cadets at the University of Alabama in Tuscaloosa before the war. He had met with Gen. Hood when the general visited the Redoubt on horseback earlier in the morning. Lumsden was told to hold the hill at all cost.

The massive attack by the Union army on December 15, 1864, came wheeling around toward the Confederate positions from the northwest and arrived in the area of Lumsden’s Alabama Battery at Redoubt No. 4 around 10:30 a.m. In the area of a ridge to the west, at what is now Estes Road, the U.S. Army deployed six batteries of four cannons each, which began shelling Redoubt No. 4 with an overwhelming barrage. The 24 artillery pieces were accompanied by approximately 4000 dismounted cavalry troops. Kay said that the Union batteries dropped 2 – 3 tons of ordnance on the Redoubt during the 4 hour battle. The din of noise of the cannon fire exchange made it difficult to hear, and the smoke made it difficult to see.

Confederate forces were not only under-manned, but under-powered. Lumsden’s Napoleon cannons had a range of 600 – 800 yards. The Union field guns had rifled barrels which could fire Hotchkiss rifled shells 1600 yards, and once they were dialed in, were capable of hitting “an area the size of a car window“ at that range. In addition, Federal forces also had the advantage in small arms. Confederate soldiers were armed with Enfield muskets, which could be fired about 3 times per minute. The dismounted cavalry for the U.S. Army were firing 7- shot Spencer repeater carbines, which could fire 21 shots per minute.

Redoubt No. 4 had fallen by around 2:00 p.m. that afternoon, along with its nearby neighbor, Redoubt No. 5. Survivors had fled downhill to the east, to join up with the Confederate line parallel with Hillsboro Pike. The action on this high ground was witnessed by Gen. Stewart, who was watching from the house of Andrew Castleman on the far side of the Pike.

Kay told his audience the story of 17-year-old Alabamian Hylan Rosser, who was in Lumsden’s Battery with his two brothers. During the artillery siege, Pvt. Rosser’s head was blown from his body by an artillery shell. Later in the evening, when Capt. Lumsden was washing up, he pointed out to Sgt. James Maxwell that he had parts of Rosser’s brain in his beard.

Above: Painting of Lumsden’s Alabama Battery in the battle of Kennesaw Mountain, prior to the Battle of Nashville. It was used by Jim Kay to illustrate what Redoubt No. 4 might have looked like.