Introduction: Below are contributions by Dr. Jim Atkinson, a member of the Battle of Nashville Trust Board of Directors, discussing medical treatment and related issues during the Civil War. Dr. Atkinson’s background makes him uniquely suited to explain and describe the challenges of medical treatment during the War. He has enjoyed a long professional career as a highly-respected pathologist at Vanderbilt University Medical Center and the Nashville VA Hospital at Vandrbilt, and as a professor at the VU Medical School. He has a special interest in the Civil War in that five of his ancestors, including his great grandfather, fought for the Confederacy from Arkansas. One of them was killed at the Cotton Gin in Franklin.

September, 2019

Disarmed: Civil War Medicine w/ Dr. James Atkinson

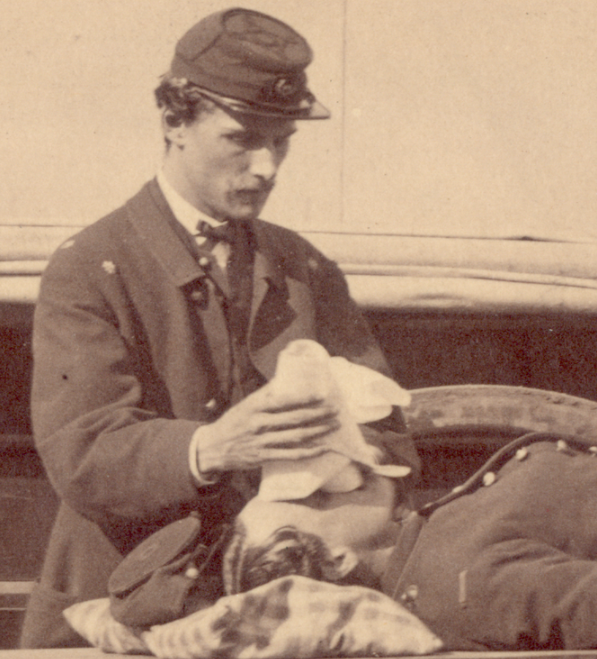

Dr. Atkinson sat down for an interview with the Dispatch, the official podcast of the Battle of Franklin Trust, in September, 2019, to describe and discuss the realities of medical treatment, especially wound management through anesthesia, surgery and recovery. To listen to the podcast, entitled “Disarmed: Civil War Medicine w/ Dr. James Atkinson,” click on the photo below depicting anesthesia, probably chloroform, being administered to a wounded Union soldier.

CIVIL WAR MEDICINE: AN OVERVIEW

By James B. Atkinson, M.D., Ph.D.

Professor, Vanderbilt University School of Medicine

© James B. Atkinson, M.D., Ph.D.

The Civil War brought tremendous advances to the practice of medicine. While the medical departments in both the North and South operated dismally at the onset of the war, when the Battle of Nashville was fought in 1864, both sides had efficient medical services that met and, in many cases, set the standard of care at that time. That dismal beginning resulted in misconceptions that have been carried even today. The recognition of disease patterns, preventive medicine, evacuation and triaging injured soldiers during battle, and treatment of serious wounds all evolved in a few short years

Over 3,000,000 soldiers participated in the War Between the States. 618,000 died. Two thirds of those deaths were by disease, and one third occurred in battle or from wounds sustained in battle. The Union lost 359,000 men. The Confederacy lost an estimated 258,000 which accounted for 1 in every 4 men of military age. The total mortality was 2% of the U.S. population at that time which is equivalent to over 6 million in today’s population. What accounted for these large numbers?

Two factors contributed to the loss of life during the Civil War. It was the first “modern” war where high numbers of casualties could be inflicted over a short period of time. With the long range of the rifled musket, soldiers were subjected to fire over a great distance, turning massed assaults into suicidal charges. The soft lead projectiles, weighing around 1 ounce, flattened and deformed on impact, causing significant damage to soft tissues and bones.

A second factor that impacted on morbidity and mortality of the two thirds of soldiers who died from diseases was that basic medical theory and surgical practice had remained relatively unchanged for hundreds of years. There were no concepts about infectious causes of illness, and soldiers lived in large, crowded camps where food and water were contaminated from both men and horses. The work of Pasteur that helped identify bacteria did not occur until the 1860’s and 1870’s, and the landmark work published by Lister “On the Antiseptic Principle in the Practice of Surgery” was not until 1867.

Many doctors in the North and South began their careers without having the opportunity to observe an operation closely, and when they were thrown into the fray, many operated largely by instinct. Trauma in the mid 1800’s consisted of the occasional horseback or industrial accident, and few doctors ever dealt with gunshot wounds. Prior to the Civil War, surgeons at one of the premier hospitals at the time, the Massachusetts General Hospital, performed less than 200 surgical procedures of any kind per year. Yet once the war began, doctors were required to perform large numbers of surgical procedures in a matter of hours. At the beginning of the war, there were 113 surgeons in the U.S. Army, 24 of whom joined the Confederate army. By 1864, more than 12,000 surgeons had served in the Union army and about 3,200 in the Confederate.

Myths Dispelled

“Doctors Were Uneducated Butchers Who Did Amputations Indiscriminately”

Military surgeons were all educated, having attended medical school or trained with an established doctor. They had to pass an exam before serving as military surgeons. The large number of amputations was because of the severe bone and tissue damage by the Minie ball, making surgical repair impossible. Because of a bad reputation promulgated by the press, Civil War surgeons were actually criticized by European and Canadian observers for performing too few amputations!

“Operations Were Done Without Anesthesia”

To “bite the bullet” is a myth perpetuated by old movies. Anesthesia was used in 95% of all operations, usually ether or chloroform, or a combination. Ether was first synthesized in the 1500’s but it was not until 1842 when a Georgia doctor, Crawford Long, used it as an anesthetic to remove a neck tumor. Chloroform was discovered in 1831 and used as an anesthetic in 1847. Both sides had ample supplies. They were dripped onto a cloth over the soldier’s face, causing loss of consciousness followed by a stage of excitement. Although the soldier was unconscious and felt no pain, he would thrash or moan and had to be held down by assistants. Since operations were performed with others waiting their turn, or in open air with passers-by, those observers saw the clamor and assumed the patient was conscious, and this was reflected in their letters back home.

“No Effective Drugs Were Available”

Infection was the major obstacle to survival after any surgical procedure since surgery was performed with unwashed hands and unclean instruments. Although antibiotics were not discovered until the 20th century, there were nonetheless effective drugs for other problems. Morphine and opium were widely used as painkillers. Civil War soldiers were vaccinated against smallpox. Quinine (cinchona bark extract) was successfully used to treat malaria. Diarrheal diseases affected virtually every soldier and killed hundreds of thousands. Although open latrines, decomposing food and unclean water were present in all camps, it was recognized as early as the Revolutionary War that people could “catch” diseases, and it was known that clean water supplies and latrines downstream helped prevent “camp fever.”

How Did Civil War Surgeons Compare to Their Contemporaries?

Civil war surgeons compared favorably to those who treated casualties in the Crimean War (1853-56) and Franco-German War (1870-71). The British had a fatality rate of 28% for 1,027 amputations. Union surgeons had a fatality rate of 26% for over 30,000 amputations. Fatality rates were higher when amputations were closer to the trunk. In every recorded amputation of the hip that was performed by British surgeons, the patient died. Union doctors succeeded 17% of the time, and the amputation of John Bell Hood’s right leg just below the hip at Chickamauga on September 20, 1863, performed by Dr. T.G. Richardson, Chief Medical Officer of the Army of Tennessee, was nothing short of miraculous.

Surgeons who served during the Civil War were generally successful in saving lives, especially considering the state of medicine in the 19th Century. Concepts conceived during the war, such as the organization of hospitals based on underlying illness, ambulance services, mobile hospital units, and triaging patients, are still very much in practice today. Even the basics of performing an amputation have not changed dramatically over the past 150 years, other than the use of sterile techniques and better anesthesia. The pain and suffering brought about by all wars since that time have further advanced medical knowledge and practice, and it is indeed possible to create good out of that evil.

_________________________________________________________________________

Part 1: Scope of the Problem and Medicine in the mid-1800’s

The American Civil War brought tremendous advances to the practice of medicine. While the medical departments in both the North and South operated dismally at the onset of the war, by war’s end, both sides had efficient medical services that met and, in many cases, set the standard of care at that time. That dismal beginning resulted in misconceptions that have been carried even today. The recognition of disease patterns, preventive medicine, evacuation and triaging injured soldiers during battle, and treatment of serious wounds all evolved in a few short years.

Over 3,000,000 soldiers participated in the War Between the States. 618,000 died. Two thirds of those deaths were by disease, and one third occurred in battle or from wounds sustained in battle. The Union lost 359,000 men. The Confederacy lost an estimated 258,000 which accounted for 1 in every 4 men of military age. The total mortality was 2% of the U.S. population at that time which is equivalent to over 6 million in today’s population. What accounted for these large numbers?

Two factors contributed to the loss of life during the Civil War. The War Between the States was the first “modern” war where high numbers of casualties could be inflicted over a short period of time. Evolution of firearms played a role. A .69 caliber ball fired from a smooth bore musket was accurate at 50 yards, with accuracy falling between 50 and 100 yards. The cylindro-conoidal “minie” ball developed by French Captain Claude Minie in 1852 was adapted by the U.S. Army. Model 1861 rifled muskets fired .58 caliber minie balls down a rifled barrel which put a spin to the bullet that extended range and accuracy. This bullet was accurate at 500 yards, with accuracy falling between 500 and 1,000 yards. With the longer range of the rifled musket, soldiers were subjected to fire over a much greater distance, turning massed assaults into suicidal charges. The soft lead projectiles, weighing around 1 ounce, flattened and deformed on impact, causing significant damage to soft tissues and bones.

A second factor that impacted on morbidity and mortality of the two thirds of soldiers who died from diseases was that basic medical theory and surgical practice had remained relatively unchanged for hundreds of years. It was just before the onset of the war that better understanding of diseases began to flourish. There was little academic medicine in the U.S. at the time, and most medical research occurred in Europe. Trans-oceanic dissemination of medical knowledge was difficult. There were no concepts about infectious causes of illness, and soldiers lived in large, crowded camps where food and water were contaminated by feces from both men and horses, and infectious disease was rampant. The work of Pasteur that helped identify bacteria as causes of certain diseases did not occur until the 1860’s and 1870’s, and the landmark work published by Lister “On the Antiseptic Principle in the Practice of Surgery” was not published until 1867. Medical theory was largely predicated on the classification of diseases as:

A. Zymotic diseases: those that are epidemic, endemic, or communicable.

1. Miasmic diseases were thought to be due to noxious substances in the air and included typhoid fever, yellow fever, malaria, diarrhea, dysentery (diarrhea with pus or blood), and many other infectious diseases.

2. Enthetic diseases that were inoculated and included syphilis and gonorrhea.

3. Dietic diseases that related to diet and included starvation, scurvy, purpura (bruising), and delirium tremens (shaking).

B. Constitutional diseases: gout, rheumatism, tuberculosis

C. Parasitic diseases

D. Local: diseases of specific organs

E. Wounds: accidents and injuries.

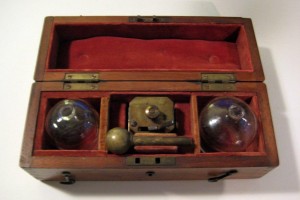

Bloodletting (bleeding) was commonly performed to cure or prevent disease . This practice, dating back to the ancient Greeks and Romans, was the most common procedure performed by doctors in the 19th century (and for the previous 2,000 years). It was based on the belief that blood was considered one of the “humors” (along with black bile, yellow bile, and phlegm) whose proper balance kept people healthy. Bloodletting was sometimes combined with cupping, in which a glass cup was applied to the skin and the air pressure inside the cup lowered by heating the cup or heating the air inside the cup with a flame which would consume all of the oxygen and create a vacuum.

Fleams and Lancets for Bleeding

Scarificators To Induce Bleeding

Cupping Set

Bleeding Cups

Bleeding Bowl

Medical Education in Nashville

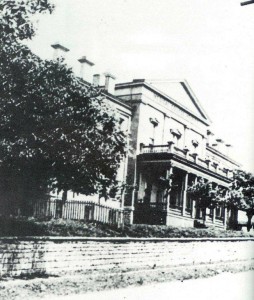

Medical education in the South prior to the war equaled that in the North. The University of Nashville established a College of Medicine in 1851. The East Wing of the school on Market Street, built in 1837, was leased to the medical college. The Union Army took possession of the building in 1862 for use as a hospital and barracks. The College of Medicine rapidly grew and ranked among the leaders of the 22 medical schools in the country before the war, and it remained open during the war. After the war, however, it did not regain its previous stature. In 1874 the school entered a joint program in medical education with Vanderbilt University which continued until 1895, when it became incorporated into Vanderbilt.

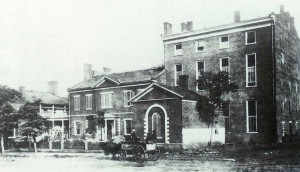

A second medical school in Nashville was Shelby Medical College, named after Dr. John Shelby who began practicing medicine in Nashville in 1817. It was a college of Central University and enrolled medical students in 1858. The medical school was housed in a beautiful mansion on the site of the old federal building at the corner of Broad and Vine streets. The City Charity hospital was build adjoining it and the college had equipment and a library comparable to the better schools of the country. After three academic years, the Federal Army requisitioned it first as a hospital, then as a barracks, and finally for refuges at the end of the war. The building was left in a dilapidated condition by the Federals and never reopened as a medical school.

University of Nashville College of Medicine

Shelby Medical College

Southern medical institutions compared favorably with their northern counterparts in every respect. Although the standards and quality of professors in southern medical schools were high, that didn’t necessarily mean that they were any better than other schools in turning out doctors who were totally capable of meeting the needs of soldiers. Many doctors in the North and South began their careers without having the opportunity to observe an operation closely, and when they were thrown into the fray, many operated largely by instinct. Trauma in the mid 1800’s consisted of the occasional horseback or industrial accident, and few doctors ever dealt with gunshot wounds. Prior to the Civil War, surgeons at one of the premier hospitals at the time, the Massachusetts General Hospital, performed less than 200 surgical procedures of any kind per year. Yet once the war began, doctors were required to perform large numbers of surgical procedures in a matter of hours. This series will later describe the most common operations that were performed during the War Between the States.