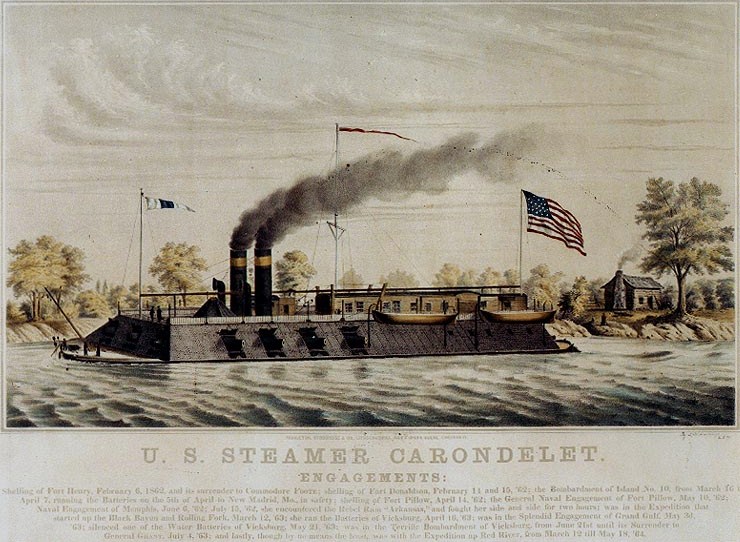

An 1866 lithograph of the U. S. S. Carondelet, which was heavily engaged at the first attack on the Confederate batteries at Bell’s Bend, December 2 – 3, 1864

Introduction: The Naval battles fought in the vicinity of Nashville are often overshadowed by the famous 2-day Battle of Nashville highlighted by heavy action at landmarks such as the Redoubts and Shy’s Hill. In this article, Nashville attorney John Allyn brings his research to bear on the military action along the Middle Tennessee rivers and gives the Naval conflicts their rightful place in the Civil War history of Nashville. John is a member of the Board of Director of BONT and currently serves as president of The Nashville City Cemetery. His articles exploring military burials in and around Nashville can be found elsewhere on the BONPS Features page. BONT was instrumental in the preservation of Kelley’s Point Battery. For more, see our Kelley’s Battery Page on the sidebar.

THE NAVAL BATTLE OF NASHVILLE

By John Allyn

© John Allyn 2011

Take a look at our list of Medal of Honor recipients at the Battle of Nashville. You’ll be surprised to see that two of the nineteen recipients are sailors, Quartermaster John Ditzenback and Pilot John H. Ferrell. Civil War Medals of Honor are sometimes suspect: they were issued wholesale in the 1890’s to politically connected (and sometimes deserving, sometimes not) veterans. But these two Medals were issued shortly after the battle – on June 22, 1865 – which suggests that there was substance to the awards. So I decided to find out more.

All the standard histories of the Battle of Nashville have a brief account of a naval action fought at Bell’s Bend on the Cumberland River between Federal gunboats and Confederate horse artillery under the command of Lieutenant Colonel D. C. Kelley. The story told by these accounts is that the gunboats were driven back by the Confederate batteries and that the Confederates maintained a blockade on the Cumberland River until driven away by Federal cavalry on December 15.

The real story is a bit more complicated. There was not just one battle – there were three. The first was a night action that covered a successful cutting out expedition by Union sailors. The second was an inconclusive daylight exchange between two powerful Union ironclads and three Confederate batteries. The final action was an attack on two separate batteries on December 15 which was coordinated with Thomas’ army. These battles marked the last naval actions in the war on western waters.

From the of James Robertson’s arrival in 1779 to the coming of the railroads in the 1850’s the Cumberland River had been Nashville’s main connection to the outside world, and remained important during the Civil War. In normal times, the river was navigable from the Ohio River all the way to Somerset, Kentucky. However, in the days before the Tennessee Valley Authority various shoals in the river were a barrier to all but shallow draft vessels at times of low water. Harpeth Shoals – which ran for several miles downstream from the mouth of the Harpeth River near Ashland City – had the most impact on river traffic to and from Nashville.

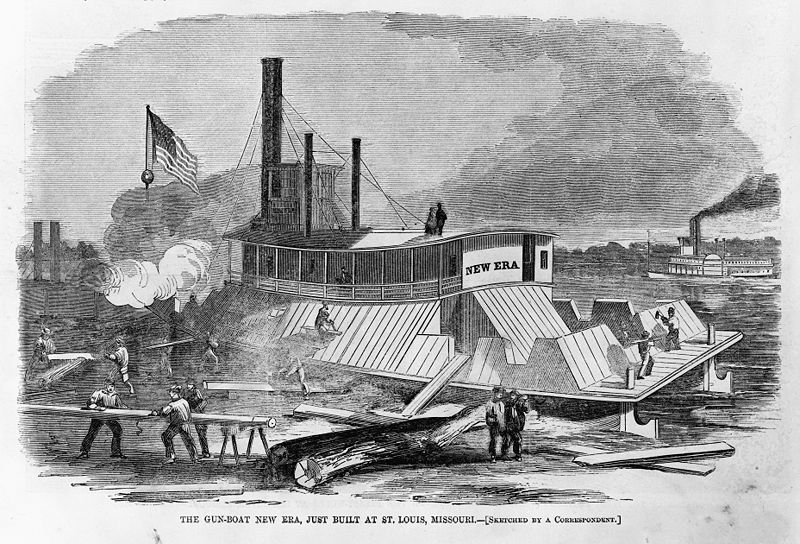

During the Civil War, riverboats were vulnerable to attacks by civilian snipers and Confederate raiders, and routine river traffic was protected by a fleet of lightly armored and lightly armed gunboats called “tinclads”. The tinclads were nothing more than armed civilian riverboats that had sheet metal armor applied to their lower decks. This protected them from small arms fire but not much else. Their vulnerability was demonstrated by Nathan Bedford Forrest on several occasions. At Fort Pillow on April 12, 1864 he drove off the gunboat U. S. S. New Era with accurate rifle fire aimed at her gunports. He captured the U. S. S. Undine at Sandy Island on the Tennessee River on October 30, 1864 after an artillery duel left her disabled. At Johnsonville on November 4, 1864 his artillery destroyed or disabled three tinclads, the U. S. S. Key West, the U. S. S. Tawah, and the U. S. S. Elfin.

The tinclad U. S. S. New Era, under conversion at St. Louis in 1862. It was armed with six 24 pounder howitzers. It was driven off by Forrest’s men during the Battle of Fort Pillow on April 12, 1864. No two tinclads were even remotely alike.

Troopships and other important vessels were escorted by full-fledged ironclads which could easily stand up to field artillery and had the armament necessary to deal conclusively with anything less than well-prepared river fortifications like Fort Donelson, Island No. 10, or Vicksburg. Imagine the lethal effect of a charge of canister from an 11 inch smoothbore Dahlgren at fifty yards, and you get the idea.

One such convoy arrived in Nashville on November 30, 1864 under Lieutenant Commander Leroy Fitch, commanding the 9th and 10th Districts of the Mississippi Squadron. This convoy carried two divisions of the XVI Army Corps under Major General A. J. Smith. Its heavy escort consisted of seven warships. I’ve put descriptions and pictures (where available) of these ships — ranging from the tiny converted river steamer U.S.S. Springfield to the giant veteran ironclad U.S.S. Carondelet — in the Appendix to this article.

The District commander was an 1856 Annapolis graduate who had commanded naval forces operating on the Ohio and Cumberland Rivers since 1862. In addition to routine escort duty, his ships were involved in the battle with Confederate cavalry at Dover in February, 1863, had prevented John Hunt Morgan’s raiders from escaping across the Ohio River in July, 1863, leading to their capture, patrolled the Mississippi after the Fort Pillow debacle, and was sent to Johnsonville in November, 1864 in a belated attempt to defend it against Forrest’s attack.

The November 30 convoy arrived just in the nick of time. Before he set off on his March to the Sea, W. T. Sherman had directed that the two divisions of the XVI Corps not with his expedition be added to the Nashville garrison to deal with Hood’s invasion of Middle Tennessee. So far in 1864 these two divisions had fought under Banks in Louisiana in the disastrous Red River campaign, fought against Forrest and Stephen D. Lee at Tupelo, Mississippi, and dealt with Sterling Price’s last attempt to return to Missouri. To say that they got around was a bit of an understatement, and they were generally regarded as among the best troops in the Union Army. This reputation would be born out in the Battle of Nashville.

On that same date as the XVI Corps’ arrival the soldiers of Schofield’s IV and XXIII Corps were at the tail end of an all night retreat from Columbia and Spring Hill to Franklin. Fortifying Franklin to gain time to rebuild the bridges over the Harpeth, they fought a sanguinary battle that evening against the soldiers of the Confederate Army of Tennessee under John Bell Hood. These two corps came into Nashville the next day, December 1, 1864.

The Army of Tennessee followed, even though it had been bled white by the assault at Franklin. James R. Chalmers’ Cavalry Division was in the lead, and approached Nashville on the Hillsboro Pike. They moved over to the Franklin Pike by way of what is now Old Hickory Boulevard in the hopes of hitting Schofield’s retreating forces, but found that they were too late. On December 2 Chalmers began moving his brigades to the northwest so that by December 3 they covered Hillsboro Pike, Harding Pike, the Nashville and Northwestern Railroad (the modern CSX line), and Charlotte Pike. Colonel David C. Kelley, commanding the 3rd Tennessee Cavalry (“Forrest’s Old”) Regiment, was sent with a detachment of 300 men and two guns to Bell’s Bend on the Cumberland River with instructions to block the river.

Colonel Kelley was an interesting person. He was an ordained Methodist minister who had raised a company of cavalry in Huntsville, Alabama in 1861. In October, 1861 the company was made part of a new cavalry battalion commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Nathan Bedford Forrest; Kelley was elected Major. When the battalion was increased to a regiment in January, 1862, Kelley was elected Lieutenant Colonel of the new 3rd Tennessee Cavalry, still under Forrest. He remained with the regiment (which had a tangled organizational history) until the end of the war. Kelley had orchestrated the capture of the gunboat U. S. S. Undine and its convoy at Paris Landing on October 30, 1864 and had placed the guns for Forrest’s shelling of Johnsonville five days later. Thus he had a certain amount of experience in river warfare.

Kelley met with almost immediate success. Three Federal supply ships, the Prima Donna, the Magnet, and the Prairie State, were carrying horses, mules, and fodder belonging to the United States government from Clarksville to Nashville when they came abreast of the newly established battery. Prima Donna and Prairie State were promptly captured; 197 horses and mules were removed as were 56 prisoners of war. The Magnet was disabled but evaded capture by drifting downstream several miles.

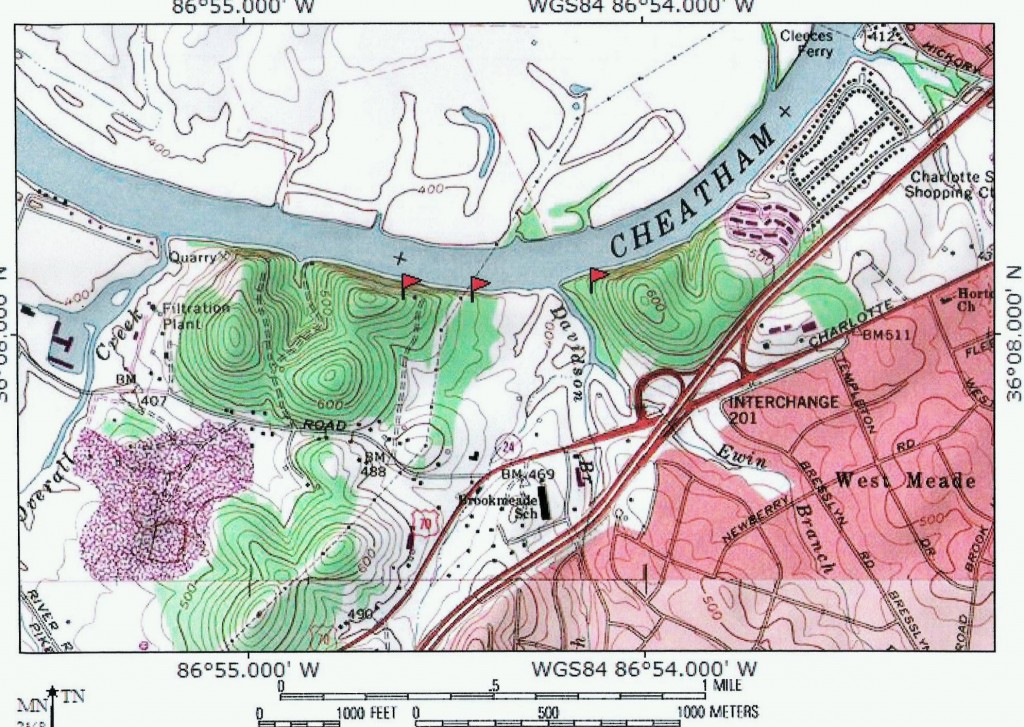

Above: Modern topographical map of the Bell’s Bend area. The river is wider today than it was in 1864 due to impoundment by Cheatham Dam. Markers show the likely location of the three Confederate batteries in the December 7 action. The middle and easternmost locations are the probable site of the two batteries during the December 4 action. The middle location is at the terminus of the modern Brookmeade Park Greenway. There was a steamboat landing at this location which is the relatively level area to the west of Davidson Branch, now occupied by the Lowe’s shopping complex. Dismounted cavalry were placed on the hills to the east and west. Click to enlarge.

At 9:00 pm on the evening of December 3, Fitch received word of the Confederate attacks downstream. He issued his orders shortly thereafter.

Carondelet, downstream at Hyde’s Ferry (in the Bordeaux area near the existing Nashville & Western railroad bridge across the Cumberland), was directed to proceed to Confederate batteries in company with the Fairplay. Their orders were to recapture or destroy the captured steamers. Osceola and Brilliant were sent to Hyde’s Ferry to take their places. Moose (with Fitch on board) and Reindeer – the two nautical ruminants – were to join with and provide cover for the Carondelet and Fairplay. Silver Lake was to stay back further and make up the rear.

Springfield was unavailable as earlier that day she had been detailed to escort army transports and supply vessels proceeding upstream from Nashville to the mouth of Stone’s River.

Fairplay, Moose, and Reindeer got underway at 9:30 pm. Carondelet, being some distance downstream from the flagship in Nashville, received her orders by messenger and got underway at 11:15 pm. She was soon joined by the more nimble tinclads.

The night was dark and clouding over – perfect conditions for an attack. Conditions on the river were such that fog could be expected; this also meant that steam and smoke from the ships would linger close to the surface of the river. This was both good and bad for the Federal fleet. On one hand, it hid them from Confederate gunners and marksmen on the riverbank. On the other hand, there was a greater risk of collision while proceeding in close formation in the fog.

The four ships formed up some distance upstream from the batteries. Carondelet was in the lead, with Fairplay following closely. Moose was immediately to the right of Fairplay, with the Reindeer 50 yards behind the Moose.

Midnight came and it was now December 4. The Confederates had their three guns in two batteries with dismounted cavalry on the two hills on either side. Between 12:45 and 1:00 am the Carondelet opened fire. At that time she was even with the lower battery and about one-quarter mile below the upper battery. The Confederates responded immediately with cannon fire, described as “warm”, and heavy musketry, described as “very annoying”. So warm was the cannon fire that the Federals grossly overestimated the number of guns firing at them, their estimates ranging from a low of four (Carondelet) to nine (Reindeer). Warm though it may have been, the fire was not particularly accurate, with all ships reporting that the Confederates were firing high. This was not surprising due to the darkness of the night, the smoke lingering on the surface of the river, and the fact that two of the four Federal ships were hugging the twenty foot bluffs on the south bank.

Traces of the Confederate gun emplacements can still be seen at Kelley’s Point. This was the site of the Confederates’ middle battery.

The Carondelet commenced firing and passed the batteries. She turned around about 300 yards downstream and proceeded back upstream, passing the batteries once again, and firing all the while. Carondelet did not take any hits. Fairplay was with her, and took two 12 pounder hits, one passing between the main and boiler decks, severing the steam exhaust pipe for the port engine, the other passing through the cabin below the pilot house. Fairplay was also struck by rifle and canister fire in several places.

The two ships then came about again and dropped downstream about two miles to Hillsboro Landing where the two captured steamers lay. This would be about where the modern Commodore Marina is located. Arriving at about 2:30 am, they caught the Confederates trying to offload forage (the horses and mules having long since joined the Confederacy) from the ships, and drove them off. Many of the Federal prisoners were recovered. The two steamers – which were disabled – were towed to the north bank of the river and repairs were begun. At 4:00 am the Fairplay continued downstream about four miles to the disabled Magnet. The Magnet was repaired and the two ships returned upstream, joining the Carondelet and the other two steamers at 6:00 am. The five ships passed the site of the batteries without being molested and returned to Nashville.

The Moose and the Reindeer had a much more eventful night. When the Carondelet disappeared into the cloud of smoke and steam, the Fairplay abruptly stopped to avoid colliding with the larger ironclad. Fitch in the Moose stooped too, but unlike Fairplay he was in the clear and became the target of both batteries. He was not able to bring his guns to bear, and so he directed the pilot to back up the river. This caused a real problem for the Reindeer, 50 yards astern. When Moose appeared out of the smoke running in reverse, Reindeer made an emergency stop which caused her to go broadside to the current, run into the north bank, and swing so that her stern was pointed downstream. All the while she was exposed to raking fire from the batteries; a bursting shell smashed her wheel.

While the Reindeer was spinning about in the current the Moose was returning fire on the batteries with her port broadside. She was able to silence the batteries. She took two hits, both dud shells. One struck her hull on the port quarter and came to rest in the bread room next to the magazine. The other struck her hull broadside and was deflected by a deck beam from going through the bottom. Regaining control, the Reindeer went upstream to rejoin the Moose, which in the meantime had come about. At this time the Confederate fire had stopped. Fitch directed that the Reindeer lash herself alongside the Moose, and the two ships remained at Bell’s Bend until morning. The battle ended a little after 2:00 am, having lasted one hour and twenty minutes.

Morning came and Moose and Reindeer were joined by the Neosho, coming down from Hyde’s Ferry. The Carondelet’s group came upstream shortly thereafter, and all returned to Nashville.

The Federals had sustained no casualties and incurred only minor damage. They had spent a lot of ammunition: Carondelet had fired 26 rounds, Fairplay 37 rounds, Moose 59 rounds, Reindeer 19 rounds, and Silver Lake (which apparently had fired a broadside at the dismounted Confederates on the eastern hill) 6 rounds.

Fitch refused to make an estimate of the Confederate casualties. His ships operated under the same disabilities as the Confederates – smoke, steam, and darkness – with an additional complication coming from the fact that the batteries were well above water level. However, it was clear that the Confederate gunners had been driven away from the river, at least temporarily.

Chalmers made no separate report of the action so we do not have the Confederates’ account of this engagement.

Later on the fourth Fitch submitted reports to General Thomas, commanding the Army at Nashville, and the commander of the Mississippi Squadron, Rear Admiral S. P. Lee (a Virginian who was Robert E. Lee’s third cousin; he had married into the Blair family which might explain why he stayed with the Union – one brother-in-law was Montgomery Blair, Lincoln’s Postmaster General, and another, Frank Blair, commanded the XVII Corps in Sherman’s army), summarizing the night actions. Recognizing that the Confederates could re-establish the batteries at any time, he told both that it was not safe yet to run convoys between Clarksville and Nashville. He said that he would reconnoiter the river again in a day or two to determine whether the batteries had been restored.

In the meantime, the river was falling fast. It was 64” deep at Harpeth Shoals, which was too shallow for all but two of the warships. Since the prospect of Confederate batteries meant that the convoys required escort, the river would have been blocked for the time being even if the batteries had not been restored.

Fitch went downriver on the Neosho on December 6. With him were the transports stranded at Nashville, escorted by Carondelet, Fairplay, and Silver Lake, which were proceeding in the wan hope that the Confederates had not returned. The convoy halted about 2 to 3 miles upstream from Bell’s Bend and the Neosho proceeded alone.

The Neosho arrived at Bell’s Bend and discovered that a very large Confederate force had reoccupied the area. Three separate batteries containing what Fitch estimated as 14 guns of various calibers, including 20-pounder rifled steel guns, let loose with a heavy volume of fire along with musketry from the dismounted cavalrymen in the surrounding hills. While there is no Confederate report to refute or confirm Fitch’s estimate, it is unlikely that he was confronted with this many guns (which would have been about 10% of the artillery in the Army of Tennessee), and equally unlikely that the batteries included anything other than conventional field pieces.

View of the Cumberland River looking upstream from Kelley’s Point. Although the river is wider and deeper today than it was in 1864, this is the view that Confederate gunners at the middle battery would have had. On December 6, 1864 the U. S. S. Neosho approached the battery from this direction, about 20 – 30 yards from the shore.

View of the Cumberland River downstream from Kelley’s Point. The U. S. S. Neosho came past the middle battery and came about, stopping abreast of the battery.

In any event, the Neosho proceeded slowly past the batteries, rounded to, and stopped abreast of the middle battery. She began firing deliberately, using grape and canister at 20 to 30 yards range which scattered the marksmen. As a monitor, Neosho was more or less immune from small arms fire since she could turn her turret towards the undefended bank while reloading. By the same token, Neosho’s fire did not have much of an effect on the batteries due to their elevation above the river. Nonetheless, she remained there for about 2½ hours, taking perhaps 100 hits, only one of which caused serious damage. A shell burst on the muzzle of one of her guns, with six to eight men being “somewhat bruised and scratched in the face” by the explosion. The Confederate fire did do considerable damage that part of the Neosho’s superstructure that was unarmored. This included the boat’s masts, on which the flag had been flying. In the middle of the action Quartermaster John Ditzenback and Pilot John H. Farrell went out of the pilot house, recovered the flag from the deck, and tied it to the stump of the main signal staff. For this, both were awarded the Medal of Honor by order dated June 22, 1865.

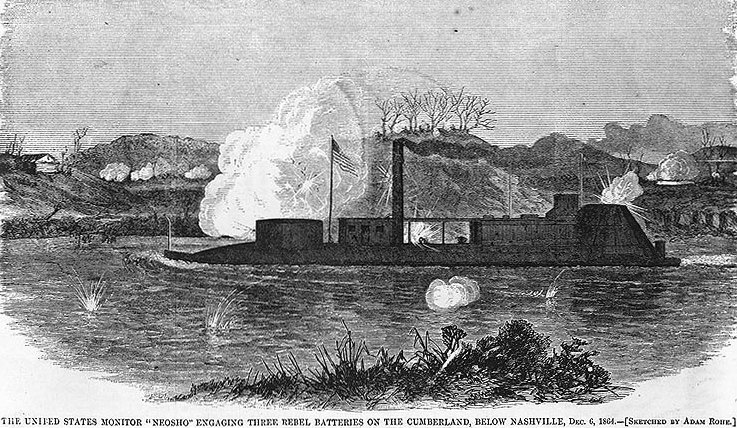

A Harper’s Weekly engraving of the river monitor U. S. S. Neosho firing on Confederate batteries at Bell’s Bend, December 6, 1864. The artist depicts the Neosho as it would have been seen from the northern bank of the Cumberland River. It is certainly not sketched from life, as the northern bank would have been a most lively place because of Confederate “overs”. The ship is moving upstream – note the bow wave, the flag, and the smoke from the stack. Fire from the lower and upper Confederate batteries is visible. The Neosho is firing on the middle battery with her two turret mounted 11” Dahlgren smoothbores.

As noted earlier, the Confederate fire had the effect of severely damaging the non-armored portions of the ship. In particular, the summer pilot house atop the superstructure had been knocked apart in such a way as to block the view slits in the armored pilot house. Fitch headed upriver to effect temporary repairs. He met the rest of the fleet and ordered the transports back to Nashville since it would be impossible to get them past the Confederate batteries without losing several. He cleared the “rubbish” from Neosho’s decks and returned downstream to the batteries, accompanied by Carondelet. Since only one ship at a time could engage the batteries directly, Fitch directed the Carondelet to make fast to the bank above the batteries while the Neosho went downstream to unmask the Confederate batteries by drawing their fire, thus marking their positions for Carondelet. This having been done, both ships opened fire on the batteries; Fitch reported that they disabled two guns, and that when the two ships returned to Nashville at dusk they were subject to desultory fire from only two guns.

The next few days were spent in making repairs to the two ironclads. Due to the severity of the weather and very low water nothing no ships were sent downstream from Nashville. Indeed, Fitch noted in his report that the object now was not so much to drive the batteries off but instead to induce them to remain so that they could be easily captured once the Federal army went on the offensive.

In the meantime, Brilliant and Springfield were sent upstream to Carthage at the request of the Army to determine whether the Confederates were active to the east, John R. Breckenridge having been reported to be at Sparta with 3,000 men. The tinclads determined that neither Breckenridge nor the 3,000 men were in the area. Later, Springfield escorted a number of steamers and barges loaded with wood downriver from the mouth of Stone’s River to Nashville, there being reports that the Confederates had sent a battery to capture them.

This routine continued until 10:00 pm on December 14, 1864 when Fitch received an order from Army headquarters notifying him that Hood’s army would be attacked early the next day. He was advised that the Confederate batteries near the river would be attacked from the rear, and was asked to engage those batteries to distract them. At the same time, he was advised that Federal forces would be in the same area, and that he should take care to avoid causing injury to the attackers.

Fitch moved downstream at daylight in the Moose, accompanied by Neosho, Carondelet, Reindeer, Fairplay, Brilliant, and Silver Lake. The Federal land force that Fritch would be

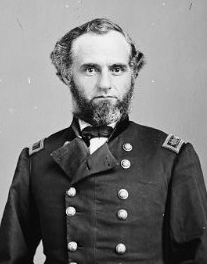

Brigadier General Richard W. Johnson commanded the cavalry division that the Navy supported during the Battle of Nashville.

supporting was a cavalry division of two brigades (one mounted, one not) commanded by Richard Johnson, a Kentucky-born West Pointer who at best could be described as one of the lesser lights of the Federal cavalry service. Earlier in the war, Johnson had been directed to deal with Confederate raider John Hunt Morgan, an endeavor that had ended with an outnumbered Morgan capturing Johnson and his entire command. His record had not improved in the intervening years.

The fleet stopped at a point about six miles downstream from Nashville. At this point there was a Confederate horse artillery battery about two hundred yards from the river, located near the intersection of present-day Kentucky Avenue and 44th Avenue North. Fitch sent the Neosho further downstream to distract the Confederate gunners. Neosho did so, and returned shortly to report that there were four guns in the battery. While Fitch felt that his fleet could readily silence or drive off the battery he chose instead to occupy its attention by feigning an attack from the river until such time as the Federal ground forces came up.

Johnson’s early morning attack was delayed by the movement of McArthur’s division of the XVI Corps on Charlotte Pike, and his attack on the Confederate cavalry line east of Richland Creek was further slowed by the fact that the troopers from his dismounted brigade who were leading his attack had difficulty advancing on foot because they had not been directed to leave their sabers behind. Eventually this was sorted out, but the attack still proceeded in fits and starts. By afternoon Johnson’s cavalry had finally gotten behind the battery. Although Fitch thought that the cavalry captured the battery, Johnson reported that it got away.

Johnson continued to drive the Confederate cavalry back along Charlotte Pike. He broke their line west of Richland Creek and drove them from a second line at Cochran’s house, somewhere between Richland Creek and Bell’s Bend. The Confederates made a final stand at Davidson’s house which Johnson described as being beyond a little creek (Davidson’s Branch) that emptied into the Cumberland opposite Bell’s Mill. Confederate artillery was emplaced on a ridge (likely where modern Brookmeade Elementary School is located). Dismounted cavalry manned a line of barricades running behind Davidson’s Branch from the river to a point some distance to the south of Charlotte Pike (likely about where I-40 passes over Davidson Road today).

In the meantime, Neosho and Carondelet had moved downstream and tied up on the north bank at Bell’s Bend. Johnson’s troopers attempted a frontal assault on the Confederate works, but were “roughly handled” and driven back. Johnson sent a messenger to Neosho and Carondelet requesting that they enfilade the Confederate line. Fitch in his report said that the cavalry was being “considerably annoyed” by a four gun battery emplaced on the side of a hill about one-half mile from the river. Heavy shells fired from his ships together with fire from the 4th U. S. Artillery attached to Johnson’s division silenced the guns and scattered their supports. Johnson reported that the discharge of the heavy guns contributed largely to the serious demoralization of the Confederates.

Johnson’s orders had directed him to wheel south to attack the left flank of the Army of Tennessee along Hillsboro Pike. Instead of obeying orders he allowed himself to be distracted by a single brigade (Rucker’s) and remained effectively out of the main fight on December 15. He went into bivouac well before sunset, assuming that Rucker would stay in place to receive his attack in the morning. Rucker was not so obliging, and Johnson woke up to find empty works in his front. Johnson tried to make the best of an embarrassing situation by making a completely unsupported claim:

“In our haste to overtake the enemy, on discovering their evacuation of the position they had taken at Davidson’s, we left behind us a battery of six guns abandoned by the enemy. They were afterward discovered, as I am informed, by forces of the gunboat flotilla and sent to Nashville. I submit that I am entitled to claim these as the capture of my division.”

When faced with this accusation, Fitch denied that he had the guns. Lending credence to this response was the fact that that in the past Fitch had meticulously accounted for captured Confederate stores. While “scrounging” is in the best traditions of the American military, it is not likely that these guns disappeared into Fitch’s ships. For his part, Chalmers in his report to his commander did not mention any lost guns, and to make a false or misleading report to Nathan Bedford Forrest was – to understate the case somewhat – not a career-enhancing move. Postwar Confederate reminiscences also confirm that no guns were lost.

Johnson ultimately rejoined the main army late on December 16 after following a roundabout route out Charlotte Pike, south and then east on what is today Old Hickory Boulevard, and north on Hillsboro Pike. His men played a minor role in the December 16 battle and a more significant role in the ensuing pursuit. On December 18 his division had gotten as far as Spring Hill. On that date the Federal cavalry commander, James H. Wilson, attached Johnson’s mounted brigade to another division. Wilson, apparently having had enough of Johnson’s incompetence, ordered him to return to Nashville with the dismounted brigade, sabers and all. Johnson saw no further combat in the war.

Afterword:

Postwar Leroy Fitch attained the rank of Commander. He died at his home in Logansport, Indiana in 1875. In 1942 the destroyer U. S. S. Fitch was commissioned, which was named in his honor.

After the retreat from Nashville, David C. Kelley and his regiment continued to operate in Alabama and Mississippi under Forrest’s command. The regiment was consolidated with remnants of other units to become the 3rd Tennessee Consolidated Cavalry. Forrest’s men were the last Confederate forces east of the Mississippi to surrender. The regiment was surrendered and paroled at Gainesville, Alabama in May 1865. He played a significant role in the founding of Vanderbilt University in 1873 and served on its Board of Trust. He also was instrumental in the founding of the Nashville College for Young Ladies, a Methodist institution which opened in 1880, and he served as its president.

He later returned to the ministry, serving as pastor to a number of large Methodist congregations in Middle Tennessee during the 1880’s and 1890’s. He died in 1909 at the age of 75.

Richard Johnson was mustered out of the volunteer service on January 15, 1866, and became provost marshal general of the Military Division of the Tennessee, and later acting judge advocate in various military departments. He resigned in 1867 with the permanent rank of major, which grade by an Act of Congress (March 3, 1875) was changed to that of brigadier general. He published A Soldier’s Reminiscences in Peace and War (1866) and a Memoir of Major General George H. Thomas (1881). He died in 1897 in St. Paul Minnesota.

APPENDIX – LIST OF SHIPS COMPRISING TENTH DISTRICT, MISSISSIPPI SQUADRON, UNITED STATES NAVY, NASHVILLE, TENNESSEE, DECEMBER, 1864

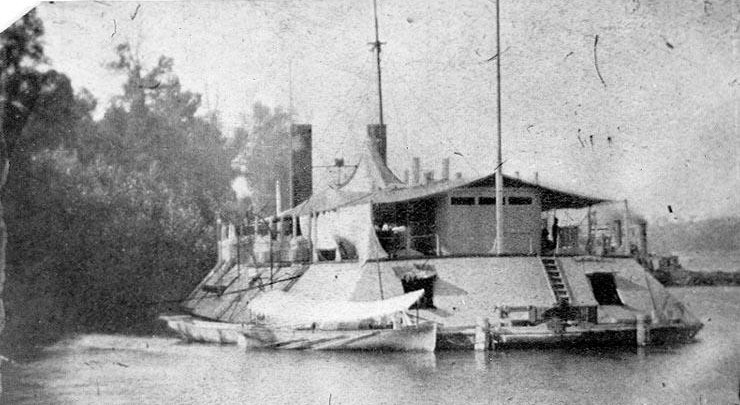

U. S. S. Carondelet at anchor in a western river. Awnings notwithstanding, just imagine how hot it must have been in that iron oven!

• U. S. S. Carondelet. Acting Master Charles W. Miller. This veteran ironclad was a veteran of all the naval actions on the western waters from Fort Henry to the Red River Expedition.

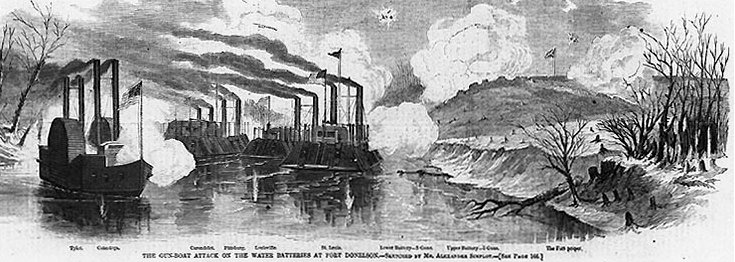

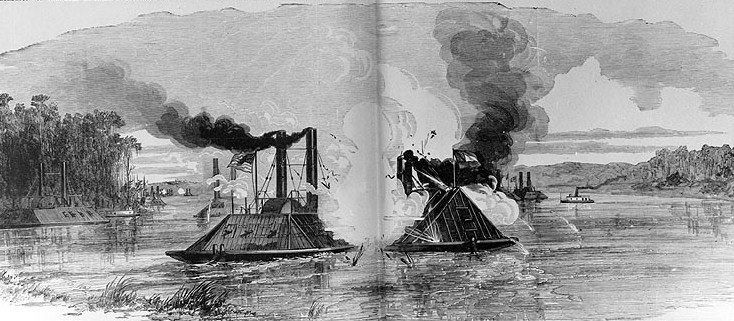

The U. S. S. Carondelet attacking the water batteries at Fort Donelson with three other ironclads. The result was a Confederate victory. The Carondelet was struck 56 times.

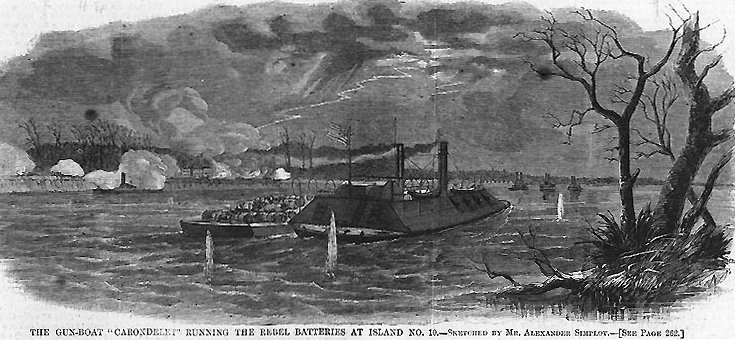

On April 4, 1862 the U. S. S. Carondelet sailed past the Confederate batteries at Island No. 10 on the Mississippi River. The coal barge lashed to her side was not only a source of fuel once she got below the batteries, but was also intended to absorb low deflection Confederate cannon fire. The batteries were cut off from resupply once the Carondelet got downstream, and her presence protected Union troops crossing the river from Confederate naval forces.

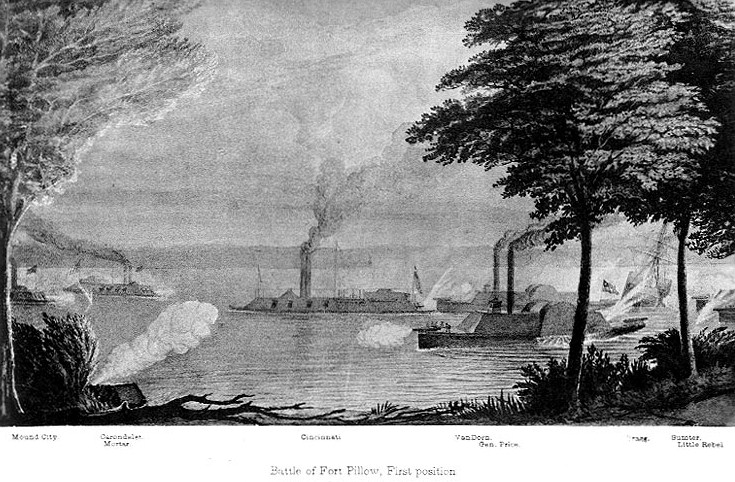

The Confederate River Defense Force, consisting of lightly armed rams, attacked a force of Federal ironclads at Plum Point Bend, just above Fort Pillow on the Mississippi River, on May 10, 1862. The ironclads, which were guarding mortar vessels shelling the fort, were caught completely by surprise. The rams holed two ironclads, both of which sank in shallow water and were subsequently salvaged. The U. S. S. Carondelet (left background) escaped damage.

The U. S. S. Carondelet was on patrol on the upper Yazoo River in Mississippi on July 15, 1862 when she encountered the C. S. S. Arkansas, an ironclad built from scratch by the Confederates in a Mississippi corn field from green lumber and secondhand railroad iron. The Arkansas had the better of the encounter. The Carondelet sustained severe damage after receiving 36 hits. The Arkansas later ran through the Federal fleet at Vicksburg and was eventually scuttled when both engines simultaneously failed during a battle with Federal warships at Baton Rouge, Louisiana.

Carondelet displaced 512 tons, was 175 feet long, had a 51 foot beam, a 6 foot draft, a crew of 251, and a top speed of 8 knots. Armament consisted of three 8 inch Dahlgren smoothbores, four 9 inch Dahlgren smoothbores, two 100 pound Parrott rifles, one 50 pound Dahlgren rifle, one 30 pound Parrott rifle, and one 12 pound Dahlgren rifled boat howitzer. She was decommissioned at Mound City in June, 1865 and sold there in November, 1865. In 1873, shortly before she was to be scrapped, a flood swept the Carondelet from her moorings in Gallipolis, Ohio. She then drifted approximately 130 miles down the Ohio River, where she grounded and sank near Manchester, Ohio. Her grave remained unknown until a May, 1982 search operation by the National Underwater and Marine Agency pinpointed the location of the wreckage, two days after a dredge passed directly over the wreckage, demolishing most of the wrecked vessel.

• U. S. S. Neosho. Acting Volunteer Lieutenant Samuel Howard. Commissioned in 1863, this ironclad river monitor had served in the Red River Expedition in the spring of 1864. She displaced 523 tons, was 180 feet long, had a 45 foot beam, a 4 ½ foot draft, a crew of 100, and a top speed of 7 ½ knots. Armament consisted of two 11 inch Dahlgren smoothbores in a rotating turret. The Neosho was put in mothballs at Mound City, Illinois in July, 1865. In 1869 she was successively renamed U. S. S. Vixen and U. S. S. Osceola. She was sold for scrap in August, 1873.

The U. S. S. Neosho at anchor, probably on the Red River. The two river monitors of this class were probably the ugliest ships ever commissioned into the United States Navy. The gun turret is at the bow of the ship; the large structure at the stern is the armor for the paddle wheel topped by an armored pilot house. False gun ports were painted on the turret to confuse Confederate gunners and marksmen.

• U. S. S. Silver Lake. Acting Master J. C. Coyle. This tinclad was built in Pennsylvania in 1862. She served on the Cumberland and Tennessee Rivers on anti-guerilla operations, shelling the towns of Florence, Alabama and Palmyra, Tennessee in the process. She displaced 236 tons, was 155 feet long, had a 32 foot beam, a 6 foot draft, and a top speed of 6 knots. Armament consisted of six 24 pound Dahlgren smoothbore boat howitzers. Silver Lake was decommissioned and sold at public auction in August, 1865. She was renamed Mary Hein and had her rig changed to side wheel by September, 1865. Fire destroyed the ship in the Red River in February, 1866.

• U. S. S. Brilliant. Acting Volunteer Lieutenant Charles G. Perkins (sick)/Acting Master John H. Rice. Another 1862 Pennsylvania-built tinclad. She served in the successful defense of Dover, Tennessee against a raid by Wheeler and Forrest in February, 1863. She displaced 227 tons, was 155 feet long, had a 34 foot beam, a 5 foot draft, and a top speed of 5 knots. Armament consisted of two 12 pounder Dahlgren rifled boat howitzers and two 12 pounder Dahlgren smoothbore boat howitzers. She was decommissioned and sold in August, 1865.

• U. S. S. Reindeer. Acting Volunteer Lieutenant H. A. Glassford. This ship and its fellow ruminant the U. S. S. Moose were built in Cincinnati in 1863. She was put into service even before she was commissioned to keep Morgan’s raiders north of the Ohio River, which led to their capture. She displaced 212 tons, was 154 feet long, had a 33 foot beam, a 6 foot draft, and a top speed of 8 knots. Armament consisted of six 24 pounder Dahlgren smoothbore boat howitzers. She was sold at public auction in August 1865 and was renamed Mariner. The ship operated as a merchantman until she was stranded and destroyed at Decatur, Alabama in May 1867.

• U. S. S. Moose. Lieutenant Commander Leroy Fitch. Sadly (at least for Rocky and Bullwinkle fans) there was no U. S. S. Flying Squirrel serving as a companion to the Moose. She displaced 189 tons, was 155 feet long, had a 32 foot beam, a 5 foot draft, and a top speed of 6 knots. Armament consisted of six 24 pounder Dahlgren smoothbore boat howitzers. She was decommissioned in April, 1865 and was sold at public auction in August, 1865. She was renamed Little Rock and operated on the western rivers until destroyed by fire at Clarendon, Arkansas in December, 1867.

• U. S. S. Fairplay. Acting Master George J. Groves. The Fairplay was built in Indiana in 1859. At the beginning of the war it was in Southern waters and was seized by the Confederate authorities. She apparently was used by the Confederates as a transport and supply ship. She was captured on August 8, 1862 at Milliken’s Bend, Louisiana by the 76th Ohio Infantry which bore the odd nickname (at least to 21st century ears) of “the Licking Regiment” because it was raised in Licking County, Ohio. She was commissioned into federal service in September, 1862. With Brilliant she participated in the February, 1863 defense of Dover, Tennessee. She displaced 156 tons, had a 5 foot draft, and a top speed of 6 knots. Armament consisted of four 12 pounder Dahlgren boat howitzers. She was decommissioned in 1865 and sold.

The U. S. S. Fairplay at anchor. This tinclad saw Confederate service as an unarmored transport prior to its capture and reconstruction.

• U. S. S. Springfield. Acting Master Edmond Morgan. The Springfield was built at Cincinnati in 1862 and was commissioned at the same time. She served on the Cumberland River on anti-guerilla operations, including the shelling of Palmyra, Tennessee in 1863. She also participated in the pursuit of Morgan’s raiders in July, 1863. She displaced 146 tons, was 135 feet long, had a 27 foot beam, and a 4 foot draft. Armament consisted of six 24 pound Dahlgren smoothbore boat howitzers. She was decommissioned in 1865 and sold. She served on the Mississippi in a private capacity until her scrapping in 1875.

____________________________________________________

ADDENDUM

After we posted this article Nashville historian Paul Clements provided us with a copy of a manuscript letter that he found in General Chalmers’ papers in the National Archives. It would appear that Demon Rum had some role in the recapture of the transports Prairie State and Prima Donna by the Union Navy. The letter was written by Lieutenant Colonel David C. Kelley to and on behalf of a Captain Chandler, who was a brigade or divisional staff officer. It would appear that Captain Chandler wished to quash any rumors that he – unlike the other Confederates at the lower battery — had been under the influence of liberated Yankee whiskey at the time the Carondolet and the Fairplay had cut out the transports. And who better to vouch for your sobriety than a Methodist minister? Just might have backfired . . .

|