THE NOT SO CIVIL WAR IN TENNESSEE

(A Different Prism)

By Philip Duer

The author, Philip Duer, is a retired Nashville lawyer and former president of the Battle of Nashville Trust. He has a keen interest in all aspects of Civil War history, especially the Battle of Nashville, and has shared his knowledge in many ways, including writing and art, ranging from ink drawings of battle scenes to creating miniature models of soldiers and equipment. As a Vietnam combat veteran who served in the 25th Infantry Division (Tropic Lightning) in 1969, and decorated with a Purple Heart, Philip has personal experience in matters of military conflict, which is reflected in the depth of his knowledge and research in this 6-part series on the “behind the scenes” aspects of the Civil War. In it, he shines a light on all aspects of guerilla warfare, especially the prolific smaller skirmishes which occurred between the more famous “named” battles of the Civil War, and the activities and dangers of spies, couriers and others that fed information into both armies before and during the battles, including the espionage actions that surrounded Hood’s Tennessee Campaign and the Battle of Nashville. To help understand how these guerilla tactics affected the war, he has added the more modern perspectives of resistance fighters in World War II, and his own experiences in combat on the ground in Vietnam.

PART I

We are all fascinated with the great battles of the Civil War; regiments, brigades, and divisions moving into action to slam into the opposing army. We are fascinated by the tactics and the military decisions that the army commanders made. We discuss what might have been if another course or tactic had been taken by playing armchair general. We are awed by the horrific battle casualties and we wonder how men could form up in line of battle to be mowed down by cannon fire and rifled muskets as a result of technology outpacing tactics.

We can all name the great battles of 4 years of conflict, but when we are called upon to put them down on paper, we are hard pressed to fill a page. Rare is the time that significant battles were fought close in time, Gettysburg and Vicksburg being the signature exception. At the start of the War months transpired between campaigns, armies going into winter quarters awaiting the commencement of the “campaigning season”. Did the War stop in those inactive periods? The answer is no.

There is a saying that all politics are local. The same can be said of combat. Doubtless many skirmishes happened in Tennessee where conventional forces faced each other in small unit actions. Most are lost to the attic of history, only to be rediscovered in long forgotten first person accounts, letters, operational records, and journals. But this article confines itself mostly to the “asymmetrical” side of the war in Tennessee.

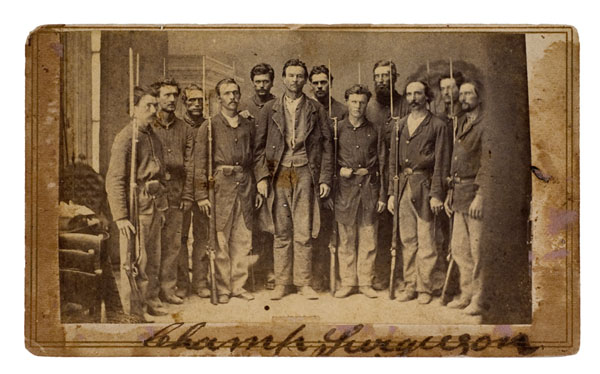

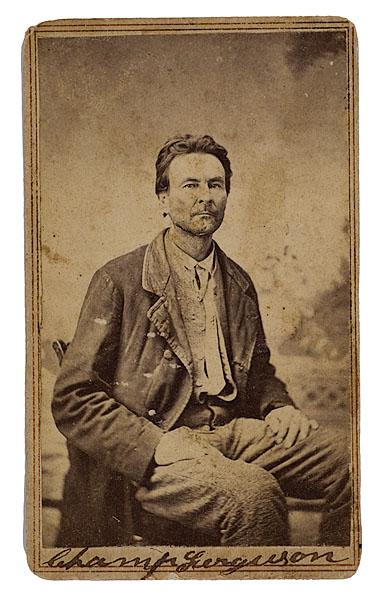

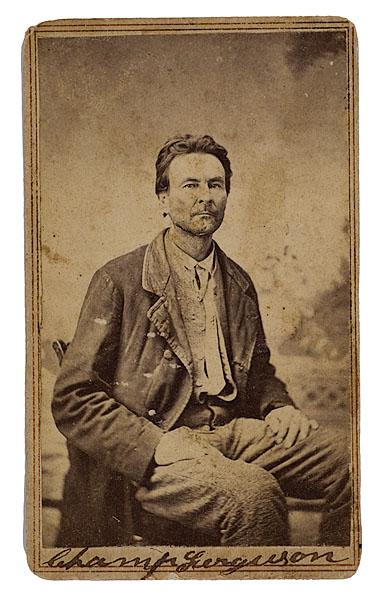

Above: Famed Confederate guerilla fighter Champ Ferguson following his capture, surrounded by his guards. It would appear that Ferguson was quite a celebrity, even to his captors at the Nashville Prison, in the same way as a John Dillinger

I have long heard that save for Virginia, Tennessee had more battles and skirmishes (10,000) than any other state. Missouri was third. But after naming the major battles in Tennessee, where and what are the thousands of skirmishes to support such a claim. Where are the sources one can go to verify this assertion….where do the numbers come from?

The answer is from a type of warfare that we think of as modern but which has been as old as Sun Tzu….”asymmetrical warfare.” Search and Destroy, Interdiction, Forward Operating Bases, Fire Support Firebases, Reconnaissance in Force, RAG’s (River Assault Groups)/ Brown Water Navy, Hearts and Minds, all tactics to combat asymmetrical warfare. Asymmetric war is guerilla war. It is based upon the tactics of ambush and hit and run with the ability to thrive in a protective and hostile population when the numbers of one side are not sufficient to meet an enemy in the field in conventional set piece battles.

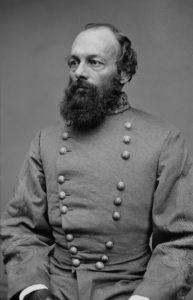

In this writer’s opinion, these tactics and the counter measures to combat them were as relevant in the Civil War as they were in Vietnam and as they are in Afghanistan. This warfare is up close and personal and the dirty side of any war. The nomenclature may be different, but the strategy and tactics are the same. Anyone who has served in this type of environment can relate to the drudgery of patrolling and the sudden terror of unexpected combat. Forrest and Wheeler were not Guerillas, but they embraced the theories of that type of war in their cavalry operations. But going deeper into the type of combat that must have occurred to constitute such a high number of conflicts in Tennessee, one is left with the assumption that guerilla war was alive and well in the South.

I decided to write this article after I was asked by a local Nashvillian to provide some information on an ancestor who initially served in the 24th Tennessee (Strahl’s Brigade, Army of Tennessee) who subsequently enlisted, it appears in the 10th Tennessee Infantry (US). The first realization is that this man was probably captured and after becoming a prisoner, took the loyalty oath to the Union and became a “galvanized” Yankee. I had assumed all galvanized soldiers were shipped west to fight Indians but it appears that it may not always have been the case.

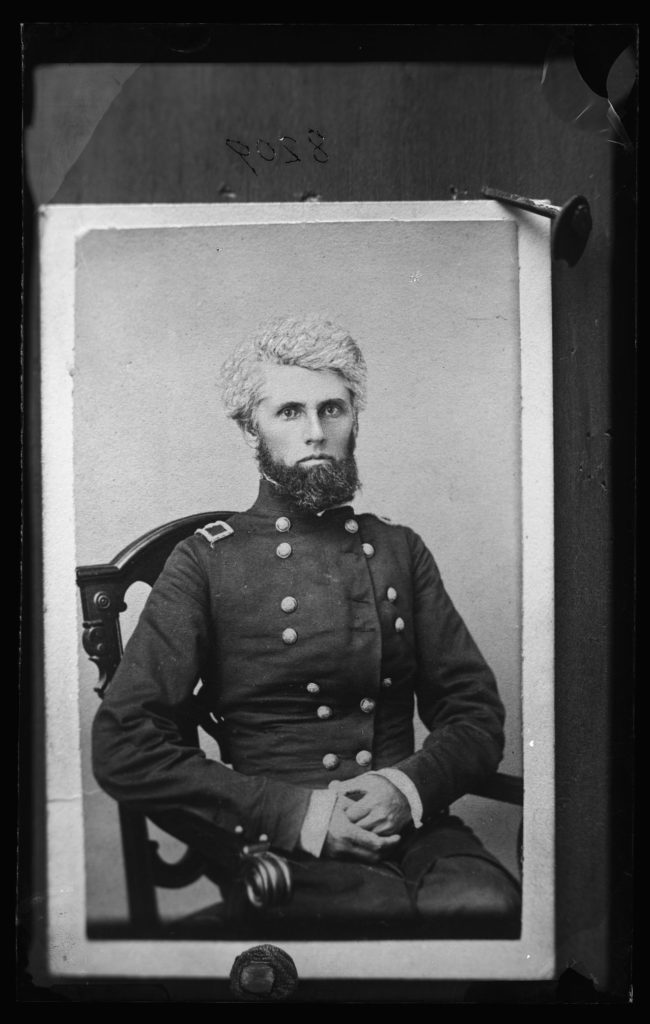

I searched some articles and books and found that the 10th Tennessee Volunteers (US) served in Nashville under Col. Alan C. Gillem, born in Jackson County, TN. This unit was formed in May through August of 1862. Gillem was subsequently promoted to Provost Marshal in Nashville and the 10th became known as Gillem’s Regiment. It also became known as The Governor’s Guard as it was posted part of the time on the Capitol grounds. Governor Andrew Johnson’s son, Charles Johnson, served as an asst. surgeon in the unit. The 10th also later provided railroad security and other protection. But in reading about this unit, I came upon after-action reports of 2 small unit patrols out of Nashville in February 1865. The mission of these patrols was to try and locate weapons and people who had been active in sniping at Union troops. These reports, by Captain Robert H. Clinton, 10th Tenn. Inf., are striking in their personal interaction with the local population. The reports can be found on the internet and I encourage you to read them. They refer to individual citizens and describe their homes. The February 12th patrol report from Captain Clinton of the 10th TN in part is set out below:

“ I proceeded on February 9th, at 6:00 pm with a force of 35 men belonging to the 14th Tennessee Cavalry of Cpt. J. L. Poston’s Company to the house of a Charles Luster, 30 miles south of Nashville at which place, according to the information, there was to be a Ball at which some 20 guerillas were to be present. 9 miles from this city on the Nolensville Pike I searched the house of a widow named Patterson whose son is a bushwacker and said to be the leader of a gang infesting that immediate neighborhood. I found one man in bed. The guide knowing nothing of him, I did not think it necessary to arrest him. In searching the house, the men found two shotguns, one Derringer pistol, and one carbine. I ordered them to be destroyed. They were loaded and ready for use. I then proceeded on the march passing through Triune at 11:30 pm…….”

The report goes on for some length. The 2nd patrol is termed a scout down the Nolensville Pike starting at 11:00 am on February 15th, 1865 to seek out armed men who were termed bushwackers interdicting and sniping on the road in the vicinity of a particular toll gate. This report is also very interesting reading and one is struck with the interaction with the local population, some citizens freely giving information to the patrol and others not so cooperative. I encourage you to read both of them.

These patrols and the people sought seem tame compared to what occurred in East Tennessee and especially on the Cumberland Plateau. Years ago, my wife and I were in an old grave yard looking at tombstones in Cades Cove in the Smoky Mountains and came upon at least one epitaph of a Tennessean “Murdered by Confederate Guerillas”.

Bushwhacking, murder, and ambush were not exclusively the tools of southern sympathizers; It was a dirty business on both sides. There were Home Guard and Partisan Rangers, the former being Union ad hoc independent units, the Partisan Rangers being the southern equivalent, both numbering as little as 5 or 6 men to the dozens, depending on the threat involved. Both were formed in part to protect the respective populace from the threats and depredations of the other, especially in the Cumberland Mountains and plateau. Whereas the main Confederate Army was ejected from Tennessee after major engagements, the small independent companies of irregulars were not so easy to defeat owing to the intimate knowledge of the terrain by the bands operating therein, most being born and raised there.

Bushwhacking, murder, and ambush were not exclusively the tools of southern sympathizers; It was a dirty business on both sides. There were Home Guard and Partisan Rangers, the former being Union ad hoc independent units, the Partisan Rangers being the southern equivalent, both numbering as little as 5 or 6 men to the dozens, depending on the threat involved. Both were formed in part to protect the respective populace from the threats and depredations of the other, especially in the Cumberland Mountains and plateau. Whereas the main Confederate Army was ejected from Tennessee after major engagements, the small independent companies of irregulars were not so easy to defeat owing to the intimate knowledge of the terrain by the bands operating therein, most being born and raised there.

The ability to “shoot and scoot” and disappear into the rugged terrain of the mountains where operations by cavalry was hampered, was frustrating to regular army units sent into sweep the rugged terrain of their threat. This is not the first time that mountain country served as protection against an army. In looking for legal cases (Shepardizing as it was called before the internet) I came across an old Tennessee Report that discussed the final ceding of land to the Cherokee who did not come out of the mountains who had eluded the U. S. Army for years after the infamous Trail of Tears. These determined men and women would not leave their land and every attempt to capture them was futile).

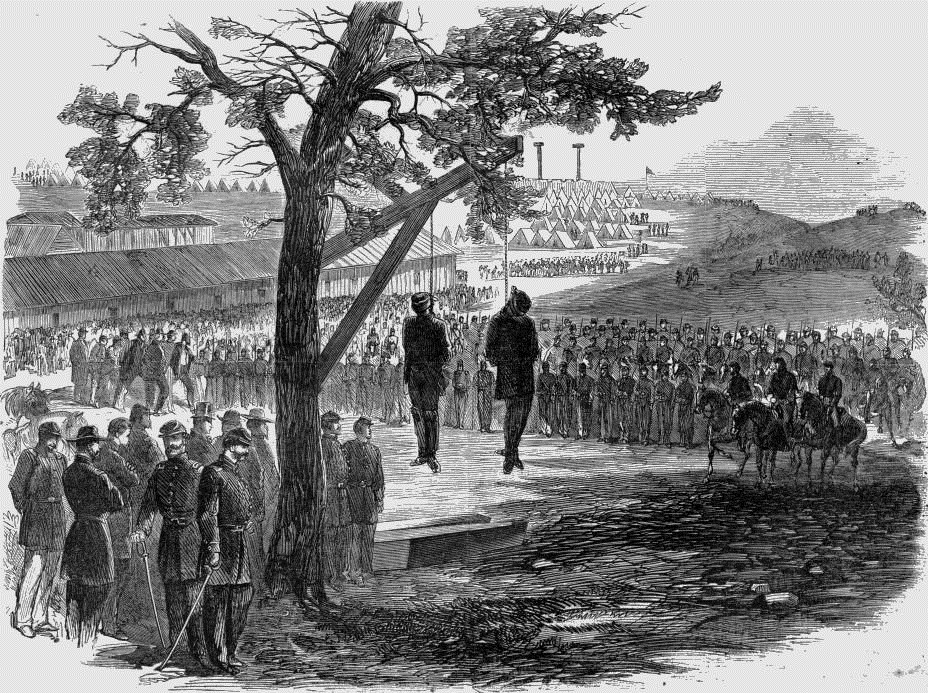

Probably the best known of the Confederate irregulars was Champ Ferguson. No other person is more associated with murder in the Cumberland Mountains and in Kentucky than Champ Ferguson. Born in 1821 in Kentucky, he was executed by the Union Army in Nashville in October of 1865 after a lengthy trial by a federal military commission. His grave is off of Calfkiller Road near Sparta, TN. At trial, his defense team attempted to prove that he was a commissioned officer in the Confederate Army and was therefore entitled to the pardon made by Grant to Lee at Appomattox.

General Thomas would have none of that and once Ferguson had been coaxed out of the mountains with the anticipated promise of just going home as everyone else (Captain Wirz of Andersonville being the other exception to the pardon), he was put in prison, tried and executed in Nashville as a war criminal. Was he any different than “Tinker” Dave Beatty, a Union sympathizer who formed the Tennessee Independent Mounted Scouts who fought Ferguson in Fentress and Overton Counties, and operated between Jamestown and Sparta? The arguments go on as to who was the most ruthless. There were old scores to settle on the plateau, many of which pre-dated the Civil War.

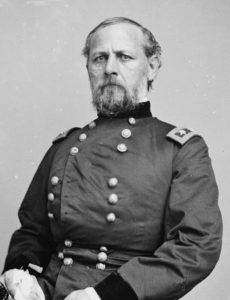

Federal troops were stationed in or near plateau country to try and pacify the area but without much success. One of the little known skirmishes, the Battle of Dug Hill, would be the catalyst for the murder of men on leave, and some of Terry’s Texas Rangers near Monterey, Tennessee, as the “Black Flag” was unfurled by Col. Wm. B. Stokes, former Dekalb County Congressman, now Colonel of the 5th Tennessee Union Cavalry who had been ordered into the area to stop guerilla activity.

Below are two drone panorama videos shot by John Banks, Civil War blogger and author, showing the countryside of Ferguson’s birthplace and burial place as of 2025.

PART II

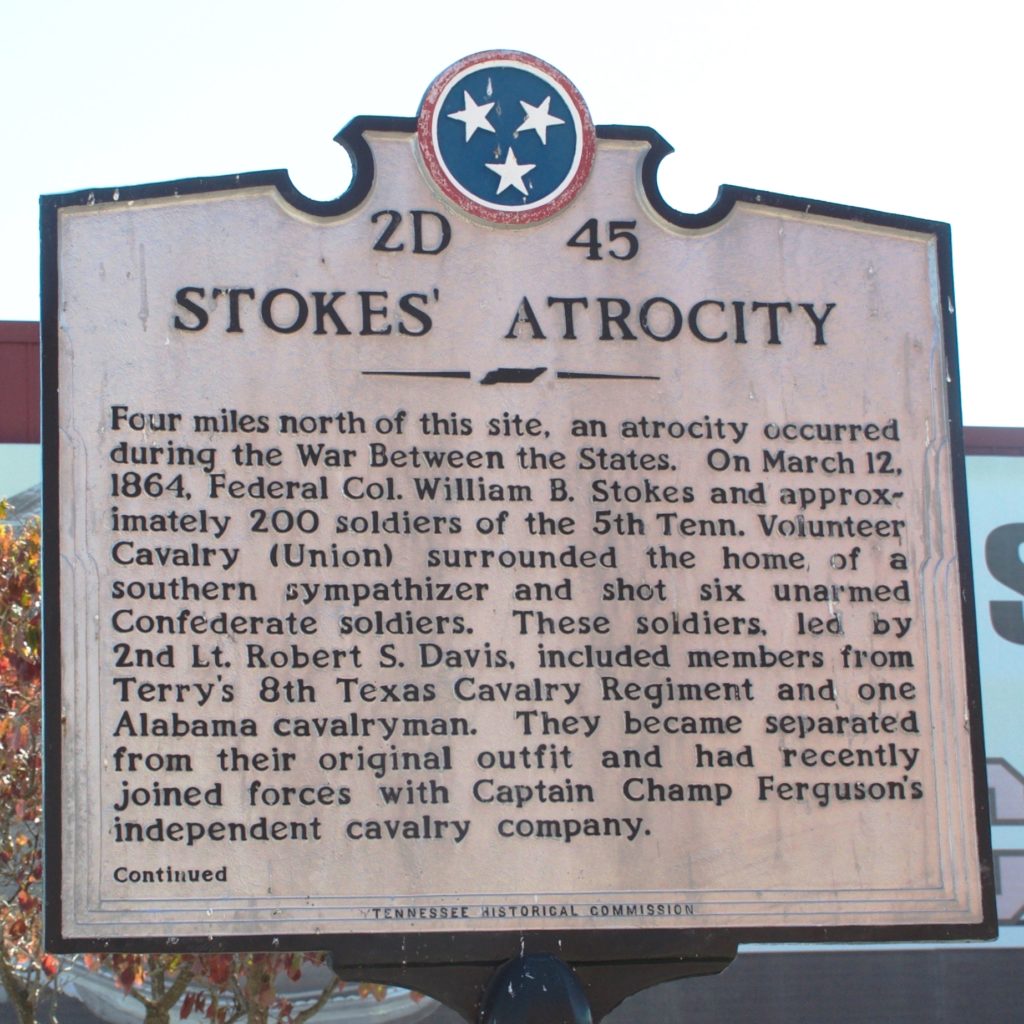

The Stokes Atrocity

On March 12, 1864, three miles north of Standing Stone, Monterey, Tennessee, William and Cynthia Officer were preparing an early breakfast for their son, a private in Dibrell’s 13th TN Cavalry along with six other Confederate cavalrymen from two Texas and one Alabama cavalry regiments. Private John Holford Officer was home on leave from his unit, the 13th TN. The other six had made their way to the Officer home after having been separated from their various commands since the Battle of Stones River. One of the men was from Terry’s Texas Rangers, the First Texas. The others were from the 8th Texas and one from the 3rd Alabama. They had supposedly made their way by word of mouth to the home as the Officers were known to be sympathetic to Confederate soldiers. These separated soldiers had spent the night. But just as they had received a tip to make their way to a friendly home, someone undoubtedly sympathetic to the Union, tipped off the federal authorities that they were there.

On the morning of March 12, 200 troopers of the 5th Tennessee Volunteer Cavalry (US) under Col. William Brickley Stokes’ command surrounded the home. The men inside realized they would be powerless even if they were able to get to their weapons, therefore did not resist, but all six were shot, five killed in the home and one wounded. The wounded man was a 2nd Lt. Robert S. Davis of the 8th Texas, who was dragged out of the house, put against a cedar gate post and shot firing-squad style. Before he was killed, an eyewitness stated that Davis said: “You ought not to do this. I have never done anything but my sworn duty.” As recent as1989, that bullet-ridden gate post was still in existence along with the Officer home.

What of Pvt. John Officer? Seeing the Union troopers dismount outside before bursting into the house, he ran into the kitchen, climbed up the loft and hid. He ultimately escaped. There is no doubt that had he been found, he would have been shot in front of his parents and suffered the same fate as the rest of the Officer’s guests.

Stokes subsequently ordered the house to be burned down, but twice, Mr. Officer put out the fire. Told if he tried to put the fire out again, he would be shot, the senior Mr. Officer appealed to Col. Stokes who finally relented and rescinded his order. A Union trooper by the name of Zeke Bass then reportedly came over to Mr. Officer and told him that it was a blessing his wife had been wounded from the gunfire inside the house; otherwise, they were going to kill him and burn his house down, but now he was going to be allowed to live so he could take care of his injured wife. Why such brutality and why no quarter given?

There is a Tennessee Historical Marker* on the main street of Monterey (Commercial Street) documenting this event and what happened. The marker states that all of the killed had recently hooked up with Captain Champ Ferguson’s company and were probably at the battle of Dug Hill. If that is the case, they were in the wrong place at the wrong time.

The men of the 5th Tennessee Volunteer Cavalry (US) had been formed in Nashville in September, 1862 from men from various Middle Tennessee counties, including Davidson, Bedford, Rutherford and Smith Counties with two companies ultimately transferred from Alabama. This unit numbered approximately 800 officers and men. The regiment saw multiple actions against various conventional forces, including Forrest, but the record is replete with the fact that it was a troublesome unit, lacking discipline, to the point that a portion of it under the command of Lt. Col. Gailbraith was cited in 1862 near Shelbyville by the division commander of the Reserve Corps as “giving me excessive trouble, and worrying and plundering through the country whenever they go out. They are under no control or discipline, as far as I can learn. Several instances have come to my hearing of their insulting unprotected females.” This report was made a year before it was ordered by General George H. Thomas in January of 1864 to Sparta to destroy the guerillas operating in that area. (This complaint would not be the last time this unit was called out in the official records. Please see the next segment to this article).

Burial place of six Confederate soldiers killed during the “Stokes Atrocity,” including Lt. Robert Davis, 8th Texas (far left of top photo). Photos by John Banks 2025.

Stokes, pursuant to Thomas’ orders, thereupon moved into Putnam and White Counties with his advance guard in February of 1864 near Yankeetown and began immediate scouting operations. Sweeps were made up and down the Calfkiller River Valley looking for contact. On February 18, he fought an engagement with various combined companies of Confederate Guerillas and Partisan Rangers under Hughs, Hamilton, Ferguson, Carter, and Bledsoe. On February 22, 1864, one of Stokes’ patrols ran into an ambush along the Calfkiller River. This battle was designated the Battle of Dug Hill by the victorious side and by the other, The Calfkiller Massacre.

Photo in gallery below taken by John Banks in February, 2025, depicting the home of William and Cynthia Officer in Putnam County, Tennessee, site of the “Stokes Atrocity.”

- default

- Grave stone of Cynthia Officer

- Main room in Officer house

- Grave stone of Lt. Robert Davis

Ambush on the Calfkiller

On February 22, 1864, 70 troopers of the 5th TN Volunteer Cavalry (US) moved down the Calfkiller River Valley on a scout between Sparta and Standing Stone looking for guerillas. They found more than they had bargained for. (This sweep would have been the equivalent of an Eagle Flight in Vietnam inserting 2 platoons into an enemy controlled area by helicopter or an Army scout platoon on the roads in Afghanistan looking to make contact or to disrupt any intended Taliban activity). A mixed command of guerillas (the estimate varies from 40 to 200) ambushed this reconnaissance patrol near Dug Hill.

After several exchanges of gunfire, the U.S. troopers were routed, quickly withdrawing and leaving their dead and wounded and those that had surrendered. What happened next sounds like more like an attack on the King’s Road by Magua and his Huron warriors against British Regulars in “Last of the Mohicans” than a Civil War battle. Moving over the battle site, the Confederate guerillas began bashing in the heads of some of the surrendering and or wounded troopers with rocks, shooting others in the head, and slitting the throats of other wounded men. It was reported that Champ Ferguson was in the fight, and may have been slightly wounded, but it is not known if he left his usual calling card — making sure no one was alive to exact revenge, by shooting them and then stabbing them in the heart. The casualties of the 5th TN varied from 38 to 21 killed but it is presumed that 21 is an accurate figure, and most, it would be fair to say, murdered.

It is no wonder that this type of violence would occur, especially with the call-out by Stokes and Brownlow (Lt. Col. James P. Brownlow of the 1st East Tennessee Cavalry Regiment (US), son of William “Parson Brownlow) that no prisoners would be taken in their operations on the plateau. Regardless of whether these statements had any added effect, murder had been the order of the day before operations by Stokes and Brownlow. One guerilla stated he captured a prisoner “once,” but he escaped. He never took a prisoner after that.

When one thinks upon how guerillas operated, what would have been the logistics of capturing, securing, and turning over prisoners to the proper authority on either side. This issue in an asymmetrical environment is still relevant and debated in Rules of Engagement, and was faced in the book and movie “Lone Survivor,” a true story by Marcus Luttrell, the lone survivor of a four-man Seal Team tasked with locating, capturing or killing a local Taliban leader in the mountains of Afghanistan. Discovered by three goatherds, one a boy, a vote was put to the team by the team leader, resulting in the shepherds being released under the Army’s R.O.E. An hour later, the team was surrounded, and all but Luttrell killed by the Taliban. Though the Seal Team was a conventional unit, and not a guerilla unit, and the goatherds were not combatants, the Seal team was operating in an asymmetrical format in a presumed hostile population.

Rules of Engagement had though been decided by both governments and in Tennessee, with regard to the Union Home Guard, it was spelled out as to what was to be done with prisoners and their transfer to appropriate authorities. But though the rules were there, the practice was generally not.

In Thurman Sensing’s book, “Champ Ferguson, Confederate Guerilla,” the author states that although the political division between the Confederacy in the west was the Kentucky-Tennessee border, the minorities of southern sympathizers in Kentucky and Union sympathizers in Tennessee were more or less evenly divided along the border which created a lot of unease among the entire population, especially those in East Tennessee and along the Cumberland Mountains and plateau.

In East Tennessee there was a failed attempt to keep it in the Union or in the alternative, to withdraw from the rest of Tennessee as a separate state. Kentucky tried to remain neutral, and entered into a neutrality agreement, but because of the acts of Federal agents, the U.S. Government began recruiting men for the Union army. A large landowner in central Kentucky near Danville by the name of Dick Robinson, donated a large part of his land for a Union training camp (Camp Dick Robinson) originally for the training of Union Home Guards which were to protect the state but the camp quickly turned into a full blown Union Army training camp. Southern sympathizers, both in Kentucky and Tennessee saw this as a violation of the neutrality of Kentucky, especially when droves of Tennesseans flocked to the camp from East Tennessee and the plateau. Southerners saw it as a possible staging area for an invasion into East Tennessee. The effect was to drive Southern sympathizers into the Confederate Army or into irregular commands.

Guerilla warfare began in earnest in the Fall of 1862 along the Kentucky-Tennessee border with guerillas from both sides invading the mountains and plateau on both sides of the border. The fault line of families became which side you chose, and once chosen, it was a repudiation, and a death warrant for those captured who had chosen a different side. There was even a futile attempt early on to stop the killing and marauding in the mountain counties in Kentucky and Tennessee, but the killing and plundering would go on.

Champ Ferguson started his killing on November 1, 1861 at the house of William Frogg in Clinton County, Kentucky (Ferguson lived in that county before fleeing to the country near Sparta, TN) . The widow of William Frogg testified at Ferguson’s trial in Nashville as follows:

“Champ Ferguson came to the house and said ’How do you do?’ I asked him to have a chair. He said he didn’t have time. I asked him to have some apples. He said he had been eating apples. He then asked for Mr. Frogg. I told him he was in bed, very sick.

“Ferguson walked in the house to the bed and said ‘How are you Mr. Frogg?’ My husband told him he was very sick, that he had the measles, and had taken a relapse. Ferguson said ‘I reckon you caught the measles at Camp Dick Robinson. Mr. Frogg told him he never was there. Ferguson then shot him with a pistol, and I started out of the house, and just as I got out, I heard another shot”….

“I had known Ferguson all my life, having been raised close by him.”

Excerpt from Champ Ferguson, Confederate Guerilla, Thurman Sensing, Vanderbilt University Press (1942)

On cross examination, it was revealed that Frogg was on leave from the 12th Kentucky Infantry. After the trial, Ferguson gave his own version to a newspaperman that Frogg was with the Kentucky Home Guard and was one of the ones responsible for his previous arrest as a Southern sympathizer but had escaped before he was taken to Camp Dick Robinson. Ferguson also stated that Frogg had intended to kill him and Ferguson had killed him first. Ferguson had a hit list of those involved which included a Union lieutenant.

Ferguson is the most notorious and well known of the guerillas and much has been written about him. He was formally accused of killing 53 men, though he had reportedly bragged he had killed twice that number. Ferguson, after the Battle of Saltville, Virginia when multiple bands had joined regular Confederate forces, as they on occasion did as force multipliers or for pilot/scouting missions, walked into a Confederate hospital post battle and sought out a wounded Union 2nd Lieutenant Smith of the 13th KY Cavalry in the Confederate Hospital at Emory & Henry College at Emory, Virginia. Between 150 to 200 Union soldiers had been captured, most of whom were wounded and hospitalized. Ferguson, accompanied by 15 or so men, dismounted in front of the hospital. Ferguson went upstairs to the 3rd and 4th floor looking for Smith. He found him, sat on his bed, patted his gun and told Smith he was going to kill him. Which he did. Smith died instantly with a gunshot to the head. Smith had reportedly been accused of terrorizing Ferguson’s family in some accounts and was on Ferguson’s hit list. In other accounts, Lt. Davis had been involved in the death of Oliver Perry Hamilton, a guerilla band leader terrorizing Unionists along the Wolf River Valley, and a friend of Ferguson; Hamilton had been captured but died in Union captivity.

The Partisan Ranger Act

Ferguson’s command was only one of a myriad of irregular units and this article is not in any way a scholarly or complete treatise on Ferguson, nor is it intended to identify all of the irregular units or an attempt to explain their exploits. Suffice it to say there were independent commands on both sides, ranging from Confederate commissioned units under the Partisan Ranger Act of 1862 (until it was repealed in 1864 at the request of Robert E. Lee and other officers for the problems and depredations precipitated by them), or the Home Guard units established by Union officers like General Ambrose Burnside. When they were caught, they were dealt with severely. General Joseph E. Wheeler promptly executed a Union guerilla by the name of Calvin Brixey, a captain in the First Alabama and Tennessee Vidette Cavalry, which was composed mainly of Confederate deserters turned Unionist guerillas, including Brixey who was a Confederate deserter after the loss of Corinth. This unit waged war in a somewhat of ‘rich man’s war, poor mans’ fight by turning against the wealthy class responsible for secession and terrorizing Southern sympathizers in Coffee, Warren, Grundy, and Franklin Counties. This unit was formed in 1863. Brixey was accused of killing dozens of men.

So as not to put the blame on just the poor men enlisting in these units, many were educated, especially the officers. Willis Scott Bledsoe was a captain and had raised a company in the Upper Cumberland to which Ferguson was from time to time attached, and who eventually established his own company. Beldsoe was an attorney who had represented Ferguson in previous criminal matters. Col. John M. Hughs was a hotel keeper in Livingston, Tennessee. James McHenry was a Livingston, Tennessee attorney. Oliver Perry Hamilton was a Jackson County, Tennessee farmer. A lot of the independent commands were established by men leaving Confederate service after their original 12 month enlistment expired and going home to establish their own fighting commands.

The Partisan Ranger Act was instituted by the Confederate Congress to gain some control and discipline over guerilla units that were operating in areas where the Confederate Army could not because of being defeated and the army’s necessary withdrawal. The Congress was approving asymmetrical warfare as another way of fighting the Union Army where its field armies could not. It provided for regular pay the same as regular soldiers but also required adherence to army discipline and control. It had one difference. For any munitions and supplies these units captured from the Union Army, the Confederate States Government would buy the captured goods. Some partisan ranger units, like Mosby’s Rangers in Virginia under the command of Col. John Singleton Mosby, were disciplined and well organized. It would be one of the two units that would remain exempt from the repeal of the Partisan Ranger Act in 1864 because of the fact that it was a disciplined fighting force. For the remainder of the guerilla bands, they became increasingly out of control and excessive in their plundering and killing. (A recommended book on plateau warfare and its devastating effects on the region’s population is Aaron Astor’s The Civil War Along Tennessee’s Cumberland Plateau (1st published 2015 The History Press)

As to the Home Guards, these Unionist guerilla bands roamed the same areas that the Confederate guerilla bands did, terrorizing citizens of the opposite sentiment, stealing, plundering, and engaging in bushwhacking of regular Confederate units and battling the pro-Southern guerilla bands. On the plateau, the most prominent was Tinker Dave Beatty. Born in the Obed River Valley in Fentress County, he stayed there his entire life surrounded by a close knit group of family and kin. As typical in mountain culture, the family was everything. When Beatty formed Captain Beatty’s Tennessee Company Independent Scouts in early 1862, it was never mustered into formal service but it was armed under the authority of Major General Ambrose E. Burnside to act as scouts and to operate in Overton and Fentress Counties. It was never paid by the Union. It was financed apparently by a Livingston physician, Dr. Johnathan Hale. Beatty is first mentioned in official records by Brigadier General George Crook in March of 1863 writing from Carthage, TN admitting his inability to establish a line of couriers due to the numerous bands of Confederate cavalry and guerillas operating in his area; he asked “Who is Tinker Dave Beatty”?

PART III

The Pervasiveness of Guerilla War In East Tennessee

An Enemy’s Country

If you believe that guerilla war was primarily confined to the Cumberland Plateau, it would be a mistake. East Tennessee and West Tennessee were truly hot beds of guerilla activity. We don’t hear much about the fact that bands of guerillas, thieves, bushwhackers, and partisan rangers moved over the countryside terrorizing Unionists and ambushing small Federal units. Some historians brush off this part of the Civil War as just a nuisance and of no real import, but it is an undeniable fact that these asymmetrical bands sapped military strength and the people enduring the struggle were traumatized from the raids or the aftermath of retribution.

If you think that the only asymmetrical activity was the province of Confederate sympathizers and guerillas, think again. Home Guards, the Unionist’s answer to the Partisan Rangers, were established in pro Union counties, not only to protect the lives and property of Union sympathizers against roving southern bands, but also to prey upon southern sympathizers to run them out of their counties. East Tennessee was not a willing participant in leaving the Union. The vote in East Tennessee was against secession. While many joined the Confederate Army and would fill out the western field army that would become the famed Army of Tennessee, many slipped over the state line into Kentucky, and those that stayed, openly rebelled.

The Bridge Burners of East Tennessee

Most people know that East Tennessee was pro Union and “full of Lincolnites,” and though East Tennessee was the last part of the state to come under Federal control, it was the first part of the state to organize to protect itself from southern sympathizers and to resist Confederate authority. Unionists had already politically organized and had formed Home Guard units in 1861 and began to harass and kill southern sympathizers and supporters. Many Unionists flocked to Kentucky in November, 1861 and were trained in camps such as Camp Dick Robinson. This exodus to Kentucky dramatically increased after April, 1862 when Confederate authorities announced that there would be conscription into Confederate military service.

President Abraham Lincoln was very much concerned about the fate of East Tennessee Unionists. In his annual address to Congress in December of 1861, one month after the East Tennessee bridge burnings, President Lincoln stated that he:

“Deemed it of utmost importance that the loyal regions of East Tennessee and Western North Carolina should be connected with Kentucky, and other faithful parts of the Union, by railroad. I therefore recommend, as a military measure that Congress provide for the construction of such road, as speedily as possible.”

Lincoln continued to voice his concerns about the fate of his supporters in East Tennessee in correspondence with General Don Carlos Buell, commanding the Army of the Ohio and his move toward Nashville two months after the East Tennessee bridge burnings:

“But my distress is that our friends in East Tennessee are being hanged and driven to despair, and even now I fear, are thinking of taking rebel arms for the sake of personal protection. In this we lose the most valuable stake in the South.”

To Don C. Buell

Executive Mansion

Washington, January 6th, 1862

In the same letter, Lincoln opens with his reasoning for moving on East Tennessee:

“I would rather have a point on the Railroad south of the Cumberland Gap, than Nashville, first because it cuts a great artery of the enemies’ communications, which Nashville does not, and secondly because it is in the midst of loyal people, who would rally around it, while Nashville is not. Again, I cannot see why the movement on East Tennessee would not be a diversion in your favor, rather than a disadvantage, assuming that a movement towards Nashville is the main object.”

To Don C. Buell

Executive Mansion

Washington, January 6th, 1862

The letter to Buell was 2 months after the partially successful attempt to destroy the bridges in East Tennessee by the Unionist Bridge Burners who had organized, with Lincoln’s financial assistance from the Federal government, to destroy bridges in East Tennessee. The goal was to disrupt Confederate movements and supplies in preparation for an invasion from Kentucky to liberate East Tennessee.

Even after official secession from the Union, several East Tennessee counties continued to send representatives to Washington. A convention was opened in Greenville, Tennessee with the primary purpose to separate the eastern section of the state from the rest of Tennessee and to join the Union as a separate state. Shortly after the Greenville petition to the Tennessee legislature was rejected, a plan was devised to blow up railroad bridges from East Tennessee to northeastern Alabama, a distance spanning over 270 miles. These bridges and their rails were used by 3 different southern railroads and were vital to the Confederacy. They provided a strategic link between Virginia, the Deep South, and what would be the western theatre.

The main planner was a retired minister, Rev. Wm. Blount Carter. He and a small group of East Tennessee conspirators traveled to Camp Dick Robinson in Kentucky and met with General George Thomas and Carter’s brother, Samuel P. Carter, a U.S. naval officer, who had been appointed as a Union Army general. Carter laid out his general plan to burn bridges to pave the way for the invasion of East Tennessee. With the bridges out, the Confederacy could not react in time to the invading federal troops and what Confederate forces there were in East Tennessee would be surrounded and captured. The plan was approved, and with a letter from General Thomas, Carter traveled to Washington and met with President Lincoln, General George P. McClellan, and Secretary of State William P. Seward. The then Tennessee Senator Andrew H. Johnson, future military Governor of Tennessee, and ultimately President of the United States, vigorously exerted his own pressure to approve Carter’s plan.

The plan was subsequently approved by Lincoln and Carter was given $ 2,500.00 to fund the operation — in today’s money, over $80,000. Carter headed back to Camp Dick Robinson to organize and train his company which became known as The East Tennessee Bridge Burners. The targets would be reconnoitered by Carter and captains selected by Gen. Thomas, Captain David Fry from the 2nd Tennessee Infantry (Union), and Captain William Cross from another regiment. The reconnaissance commenced in Mid October, 1861, the men travelling from county to county to select the bridges and to secure a local neighborhood leader with 5 or 6 loyal Unionists to attack each selected bridge. The firing of the bridges would be the signal for all Unionists to rise up in arms against the Confederacy.

On the selected night of November 8th, 1861, the bridges were targeted, from Union (Bluff) City on the Holston River to Chattanooga and Bridgeport, Alabama. The rest is history — five of the nine bridges were successfully destroyed with the remaining four damaged.

But what of the planned Union invasion? There was in fact a federal army ready to invade from Camp Dick Robinson to take Knoxville, but because of raids by General Zollicoffer into Eastern Kentucky, though defeated in October, 1861, and the subsequent movements by the Confederate Army in the West, the then Department of the Ohio commander, Genl. Don Carlos Buell believed he was stretched too thin, and halted the invasion even though McClellan had urged its going forward. General Thomas, now a division commander under Buell’s jurisdiction, pleaded with Buell to move on Knoxville; he was only 40 miles from the Cumberland Gap, but on October 30, 1861, Buell called off the invasion scheduled for November 7. Buell’s tactical focus, and in fact, most Union military commanders eye’s, were on West Tennessee.

Astoundingly, this vital fact, that there would be no invasion, was never communicated to Carter, nor Captains Fry and Cross, nor was it relayed to any other Unionist. The Bridge Burners therefore proceeded with their plan in the belief of a concurrent federal invasion. Without detailing the actions of these brave and determined men, the operations were successful at some locations, but bungled at others, one failure, for example, arising from the loss of matches in the dark when the saboteurs scuffled and were wounded by a Confederate guard.

Though the federal invasion did not materialize, the burning of these bridges sent shockwaves through the Confederate government, fueled by wild stories of East Tennesseans suddenly rising up. In fact, on November 9, 1861, believing the invasion was on, over 1,500 Unionists from all over East Tennessee gathered at a local farm near Elizabethton in Carter County in East Tennessee to organize, with some Unionists battling local Confederate cavalry posted there, causing the unit’s withdrawal. The account was picked up by the Richmond Dispatch and reported by the New York Times (digitized and online):

“There are report of the burning of two bridges on the Georgia and Tennessee Railroad. And some facts have been communicated to us relative to an attempt to burn the long bridge at Strawberry Plain. Near Knoxville. The man who was stationed there to guard it saw 15 men approach. And used his pistol and double barrel shotgun with such effect as to keep them at bay until assistance arrived: but he was very badly wounded himself. Two or three at rests have been made of suspected parties in the neighborhood”.

Richmond Dispatch, Nov. 20, 1861

The Richmond Dispatch also reported a skirmish with a large force of Unionists in Carter County by a small Confederate reconnaissance party:

“… The Lincolnites were some three hundred strong. and constituted the advance of a body of eight hundred. Stationed in Elizabethtown. The mountain stronghold of the traitors. We may state here that these men (as has since been ascertained from prisoners) expected a reinforcement of 500 men from Watauga County, North Carolina- a disaffected region adjoining Johnson City. Tennessee”.

Richmond Dispatch, Nov. 20, 1861

While the Union Army delayed, the Confederate government took swift action against the bridge burners. Col. Danville Leadbetter was immediately ordered to East Tennessee to oversee the bridge repairs by the Confederate engineers and to protect the bridges and railroads. Co. W. B. Wood, commanding Knoxville and its environs, wrote Confederate Secretary of War Judah P. Benjamin On November 20th, 1861:

“The rebellion in East Tennessee has been put down in some of the counties, and will be effectually suppressed in less than two weeks in all counties…we now have in custody some of their leaders, Judge Patterson, the son-in-law of Andrew Johnson, Col. Pickens, the senator from Sevierville, and others of influence and some distinction in their counties….they really deserve the gallows, and, if consistent with the laws, ought to speedily receive their desserts……”

Col. W. B. Wood

to J. P. Benjamin, Secretary of War

Confederate States of America

Letter November 20, 1861

Secretary Benjamin’s response, 5 days later, was especially sanguine:

“Sir, your report of the 20th instant is received, and I now give you the desired instruction in relation to the prisoners of war taken by you among the traitors of East Tennessee. First. All such as can be identified in having been engaged in bridge-burning are to be tried summarily by drum-head court martial, and if found guilty, executed on the spot by hanging in the vicinity of the burned bridges. Second. All such as have not been so engaged are to be treated as prisoners of war, and sent with an armed guard to Tuscaloosa, Alabama, there to be kept imprisoned at the depot selected by the Government for prisoners of war…”

Judah P. Benjamin

CSA Secretary of War

to Col. W. B. Wood, CSA

Letter November 20, 1861

A dragnet was thereupon undertaken and hundreds of suspected Unionists and activists were arrested and shipped to prison in Alabama, including Senator Pickens (who died there) and newspaper editor William G. “Parson” Brownlow who was suspected of organizing the attacks and who had been surprisingly allowed to publish his Unionist sympathies in his newspaper pre bridge burning, the Confederate military department leader at that time, General Felix Zollicoffer, exerting a relatively light hand on Union sympathizers. That changed after November, 1861. Zollicoffer tightened control of his department.

The afore-mentioned, Col. Ledbetter, in charge of the military sweeps looking for the guerillas reported the details of his actions:

“At the farmhouses along the more open valleys no men were to be seen, and it is believed that nearly the whole male population of the country were lurking in the hills on account of disaffection or fear. The women in some cases were greatly alarmed, throwing themselves on the ground, and wailing like savages”.

In the end, 5 Bridge Burners over a 5 week period were hung, with one convicted and to be hung, pardoned upon a plea by his daughter to President Jefferson Davis. William Carter, to his death after the War, never revealed the names of any conspirators or actual bridge burners, many never being revealed.

Though the military impact was negligible, the political impact was dramatic. Confederate control tightened. When Confederate General Edmund Kirby Smith, appointed in February of 1862 to the command of the newly formed Army of East Tennessee, marched into the region to exercise control over the population, he soon observed that the reality on the ground was not what was related to him.

Happy as a division commander in Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia, and as a major general, he saw his posting to East Tennessee as an isolated backwater devoid of the promise of enhancing his military career and promotion. He had relocated his family to Lynchburg, Virginia where he was surrounded by a loyal southern population, but he would soon find out that his East Tennessee posting was one where he was forced to govern a hostile isolated population. Upon his arrival he soon wrote to his wife in Virginia:

“I find affairs here, as far as I am able to judge, in a much worse condition than represented.”

On March 13th, 1862, Kirby Smith wrote:

“No one can conceive the actual condition of East Tennessee, disloyal to the core, it is more dangerous and difficult to operate in than the country of an acknowledged enemy.”

A day later, on March 14, 1862, he wrote Major General Braxton Bragg decrying:

“East Tennessee is an enemy’s country, its people beyond the influence and control of our troops and in open rebellion. The force here at present is barely more than sufficient to guard the Pork Houses and the line of the railroad.”

Smith had too few men to control such a large area. He was expected to guard the railroads and bridges, keep troops trained and ready for any invasion, keep Union sympathizers from slipping away into Kentucky, and to convert the population to the Southern cause, or to at least keep it from interfering with Confederate authority. Some of the units under his command were local militias, which on the whole were disloyal and suspect as well as some locally raised regular units, believed to be unreliable. In addition, many units had little training and few arms. Large areas were unable to be patrolled, as for example, Chattanooga, being almost unguarded. Kirby Smith in his own correspondence stated he had no more than 2,300 men to guard the Cumberland Gap, a major invasion route. Smith felt increasingly isolated when Union victories at Forts Henry, Donelson, and the Battle of Shiloh forced the withdrawal of Confederate forces from the State.

Nevertheless, Kirby set about his task of trying to pacify East Tennessee with extraordinary zeal and relative even-handedness. In order to feed, clothe and arm his forces, he instructed his officers to take food and supplies first from the Unionists, then Confederate sympathizers, but always paying for them. He told his officers that he would hold them personally responsible for the actions of their men.

His beliefs were the same as Zollicoffer who was killed in January of 1862 at the Battle of Fishing Creek (Mill Springs) in Kentucky. Both believed in punishing overt acts of resistance but not beliefs. He approached the problem with the strategy of “Winning the Hearts and Minds”. He erroneously believed that if you could remove the men who misrepresented Confederate intentions and the firebrands fomenting revolt, the rest of the population would accept Confederate authority. He, like Zollicoffer separated overt acts from disloyal beliefs, punishing the former, but tolerating the latter.

On April 2, 1862, Kirby Smith wrote to the Confederate Adjutant and Inspector General, Samuel Cooper:

“The arrest of leading men may bring these people right. They are ignorant, primitive people, completely in the hands of, and under the guidance of their leaders…”

When newly elected county officers and administrators across the department were set to take their respective oaths of office, Smith secretly detailed officers with 25 man squads to observe and make sure all swore allegiance to the Confederate government. For those that did not, they were to be immediately arrested and sent to Knoxville. A few refused, but most did take the oath, obviously choosing an accommodation rather than embracing the Confederacy. Other loyalists continued to be arrested.

Though many were arrested by Smith’s men, they were tried in civilian courts as martial law had not been declared. Many district judges, sympathetic to their Unionist neighbors, freed many accused of rebellion because of the lack of proof under the law. Writs of habeas corpus were issued by the courts for persons held by the military. Kirby petitioned the government at Richmond for the right to declare martial law and to suspend habeas corpus which was granted, but only in East Tennessee in early April, 1862. This authority gave him the power he needed. He appointed military commissions to oversee the civilian courts to insure they acted fairly. He had the authority to establish a military police. The power of martial law allowed him to go after influential people who were Unionists by putting them in jail or expelling them from the State without intervention from the civilian courts. He ordered cavalry patrols to picket and watch the state border with Kentucky and to arrest those that sought to enter Kentucky to join the Union Army.

In mid April of 1862, Smith offered a general amnesty and forgiveness to those that would stop resistance and take the oath. This amnesty was even extended to East Tennesseans in the Union Army provided they returned to the State within 30 days. In addition, if they returned and brought in their arms and equipment, they would be fairly compensated.

Kirby Smith was even allowed by the Confederate government to suspend the draft in East Tennessee which had been implemented by the Confederate government in the Spring of 1862, so as not to antagonize the Union sympathizers any further. He recommended that East Tennessee raised volunteer regiments be sent to other states in exchange for other state units from other states in the hopes of having reliable troops in East Tennessee and the raised East Tennesseans becoming more loyal to the Confederacy in another state. This was agreed to by Robert E. Lee provided the East Tennesseans enlisted for 3 years.

As stated, Smith was primarily responsible to defend East Tennessee from a likely invasion. This he attempted to do with few resources. Without going into the details, it was fortuitous that there was no early attempt at invasion, primarily because of the fear of the logistics in keeping a supply line open due to the anticipated guerilla activities and attacks by Confederate cavalry. One only needs to look at the topography to understand a Union military commander’s dilemma in moving on the eastern part of the State.

Nevertheless with Union movements westward toward middle and west Tennessee, Generals Bragg and Smith saw a military vacuum in Kentucky and invaded the State. With Kirby Smith’s suggestion, a new department commander was chosen by Secretary of War George Randolph, Major General John P. McCown. He was a Sevier County native, but his tenure was unsuccessful, so a fourth department commander was chosen by Randolph, Major General Sam Jones, who had been Beauregard’s chief of artillery and had fought at 1st Manassas.

Jones was dedicated to pacifying the population and appeared to be more sympathetic to the plight of Union sympathizers. But Secretary of War Randolph directed that his first priority was to enforce the reinstated conscription laws in East Tennessee without causing a revolt. No one in the South had liked the draft laws, and many who were aware of East Tennessee’s exemption, were resentful. In addition, martial law was not favored by the Confederate government and was rescinded, but conscription had been reinstated. Jones asked that East Tennesseans again be exempted. This second request fell on deaf ears. The Confederate government was already irate that a part of the Confederacy was in open rebellion and wanted East Tennessee to be brought to heel. In addition, the Confederacy needed to replace substantial losses from Perryville and Antietam. Richmond also needed the foodstuffs and supplies, as well as manpower from this part of the State, and consequently in September of 1862 rescinded the request granted to Kirby Smith that the food production and supplies stay in the region. They now would be shipped to other parts of the Confederacy where needed. In the end Confederate conscription became the best weapon to combat rebellion in the eastern part of Tennessee, though Jones continued to seek cooperation with the leaders of the pro-Union region, even inviting some to publish in local newspapers their views toward accepting cooperation, or at least tolerance.

In September of 1862, the Emancipation Proclamation by President Lincoln after Antietam, surprisingly saw some Unionists revolt at what they saw as the unconstitutional “taking” of property from the South and, in freeing slaves. Some saw the military need, some saw it as violation of law, and others saw it as Confederate propaganda and untrue. But most Unionists remained pro-Union. The department commander used the proclamation to his advantage to drive a wedge into Union sympathies.

After Perryville, Kirby Smith returned as department commander, but in December, 1862, Smith was transferred to the Trans Mississippi Department. His successor, Brigadier General Daniel S. Donelson assumed command and exerted a harsh hand on pro-Union sympathizers, but his command was short lived. Major General Simon B. Buckner was subsequently appointed replacing Donelson, and though martial law had been rescinded by Richmond, he enforced it without authority, jailing Unionists and refusing to release them even when civilian courts issued writs of Habeas Corpus.

As written by one historical writer, East Tennessee possessed a reputation in the South as a backward impoverished region, inhabited by ignorant mountaineers. This belief was also held by most of the confederate troops who were ordered to the region. With the hatred of a great deal of the population being felt, or because of actual acts of violence, many troops responded with hatred and violence. Houses suspected of harboring Unionists, whether just sympathizers or guerillas, were looted, burned and property taken, whether horses, slaves, or foodstuffs. People were arrested and jailed just because they were suspected of having Union sympathies.

Zollicoffer and Smith’s separation of overt acts from beliefs became an academic nicety. All were traitors and were to be treated accordingly. East Tennessee became a devastated region, one of mutual fear, hatred, and poverty.

It would be two long years before East Tennessee was liberated by the invasion of General Ambrose P. Burnsides in mid-1863 with an army of approximately 5,000 men. His invasion was unopposed, but his action would prompt the attempt by General James Longstreet commanding 17,000 men moving from the Chattanooga siege conducted by General Braxton Bragg and the Army of Tennessee, to retake East Tennessee. Longstreet besieged Knoxville in mid November, 1863. After receiving reinforcements, Longstreet attacked and was severely repulsed at the Battle of Ft. Sanders on November 28th, 1863. Continuing to lay siege in the hopes of drawing federal forces from Chattanooga (which was successful, ultimately diverting some 25,000 Union soldiers), Longstreet did not leave East Tennessee until forced by overwhelming Union forces. Longstreet subsequently rejoined Lee and the Army of Northern Virginia in the Spring of 1864.

A regimental officer in the 36th Massachusetts in Ambrose’s army, William Franklin Draper, noted upon entering East Tennessee that he would know he was in East Tennessee “by the number of houses destroyed or abandoned.”

East Tennessee would never be wrested from Federal control from that point forward. The tables were turned…it would be the remnants of Southern guerillas and Confederate sympathizers, not Unionists, who would pay the price. Union control would not make any academic distinctions.

A Few Modern Thoughts on An Old Issue

Being stationed in a hostile population, being in a land where friend cannot be identified from foe, because no one wears a uniform, your thought process for survival is simple and direct, everyone is an enemy until otherwise proven. The farmer in the field that waves at you during the day, can plant a booby trap at night, injuring or killing you or your comrades on patrol the next morning. Powerless to identify the culprit, the inclination is for immediate revenge, “payback.” But who do you exact revenge on? Fighting a main force unit is different, though more deadly and infrequent, but you know who and where he is. You can engage him. The easiest justice in your mind is to believe that it is the farmer in that field……HE DID IT, or at the very least, he knows who did it, and he didn’t give you any warning. The distinction between sympathies and overt acts do become academic, and they become meaningless. Either way, that person is the enemy and is going to pay. So, how does that revenge keep from being implemented. It is training to a degree, for sure, and the rules of engagements and fear of punishment, but more importantly it is having good officers and NCOs. As stated in the Vietnam book, “Dispatches,” nothing is more dangerous than an 18-year-old with a gun.

The actions of Lieutenant William Calley in Vietnam in May of 1968 in failing to exercise control over the company he was leading under the command of Captain Ernest Medina at My Lai is a tragic, but perfect example of failed leadership. The reason the company went wild and in bloodlust was the fact that Charlie Company had suffered serious losses up until then and was down to approximately 100 men. They were told by command that in the area they were inserted on a search and destroy mission, that all were VC or Vietcong sympathizers and had taken control of another village. With this information, Charlie Company came in ready for battle. This was several months after the start of the Tet Offensive. What they found at My Lai was a peaceful village, not one shot was reportedly fired by anyone other than American soldiers, but over 500 civilians were killed, many raped, and some mutilated. Some soldiers did not participate and tried to stop the killing, but it was only after a warrant officer flying a Huey helicopter on reconnaissance spotted what was going on and landed his helicopter between the surviving villagers with the door gunners aiming their M-60 machine guns on those soldiers out of control, that the killing stopped.

To this day, I have met several soldiers who served in the Americal Division, to which Charlie Company was a sub-unit. We always knew the division as the “Americal.” After the first veteran I met who told me he had served in the 23rd Infantry Division, I suspected he had not served and it was a stolen honor example. After I heard another veteran later on say that he was in the 23rd, I was curious and looked it up…..it was the Americal. I can only assume the shame of My Lai was the reason they did not give the name we knew them by. The Americal served with distinction and honor, but it only took one event that forever stained the men who served honorably.

Unfortunately, Charlie Company was not the only American unit in Vietnam responsible for acts of outrage by its soldiers, but those instances pale in comparison to the atrocities of the Viet Cong and North Vietnamese Army. The average American unit and its soldiers served with honor. With the Viet Cong, atrocities perpetrated on U.S. soldiers, South Vietnamese (ARVN) troops, and especially civilian,s were right out of their playbook, not as isolated events, but as tools of intimidation and fear. But that is the horrible underbelly of guerilla warfare.

I offer this example because the same feelings must have pervaded the minds of many of the men who served in East Tennessee, whether Union or Confederate. We don’t see the war from that lens, only the big battles. We don’t see the everyday ugly and acrimonious struggle, of troops being suddenly ambushed, of civilians being hassled, of retribution, of the heavy footprint of an occupying army, or in some cases the outright murder or assault on prisoners, civilians, or captured soldiers, by both sides.

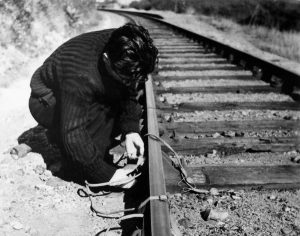

One of three positions on pontoon bridge at Phu Cuong. Note TNT charges that have been assembled to throw in River. Photo by Philip Duer

I served in an infantry company in the 25th Infantry Division based out of a firebase west of Saigon toward the Cambodian border in early 1969, but my first duty with my platoon was guarding a large concrete bridge, the Phu Cuong, on the Saigon River. I got there in January of 1969. Our job was to protect the bridge and the vital highway. In November of 1968, an NVA sapper unit had blown a section of the bridge. In January, 1969, I was one of the guards in shifts detailed to the pontoon bridge that had been constructed to keep military traffic going until the permanent bridge was rebuilt. Our job was to assemble and throw TNT ¼ lb sticks in the water from the pontoon and from the positions under the main bridge, day and night to kill any underwater demolition squads. I met a lot of Vietnamese crossing the pontoon who lived in the town and they were friendly and at ease. It was a provincial city and pacified.

At the firebase, our job was to go out each day on helicopter assaults, to search and destroy along one of many suspected infiltration routes used by the North Vietnamese Army (the VC had been pretty well decimated by then as a result of Tet). Most of the time we did not make contact, but when we did it was a terror. I had many experiences with the civilian population who were farmers in the country. They were not as friendly as their city brethren as they unwillingly bore most of the war. They were polite, but mainly tense and viewed us with a watchful eye. I look back on it now, of going into family hootches (houses) unannounced, sometimes at night, with my M-16 protruding in before my helmet did, going through possessions and going out the door, trying to give a smile, and they, you, always with a tense look; of digging up fresh graves with the villagers looking on in silence, the reason for exhumation being trying to ascertain whether it was a weapons cache, and not a dead body, and stopping once you reached the smell; of a Vietnamese farm lady who had laid out her peanut crop on the hard packed dirt at her farm at the edge of a little hamlet, trying to shoo us away from eating her crop, and we moving out after dusk, knowing we were being watched, to set up a night perimeter and the VC mortaring her little farm, thinking we were still there; of killing a water buffalo, the farmer’s most valued possession, when she and her calf broke out of her stall and got into our tactical formation. Of free fire zones, in which everyone was considered an enemy combatant and subject to being killed, the area being theoretically clear of civilians, the civilians having been rounded up and re-settled in strategic hamlets. I could go on.

Bunker at Phu Cuong bridge, noted by Philip Duer (who took this photo) to be the same as a Civil War blockhouse providing security for a bridge, road, or railroad from cavalry or guerilla raids.

Like the soldiers in the Civil War detailed to East Tennessee, we were prepared for hostility from the get go when we got on the buses to take us to the replacement pool at Long Binh after deplaning at Ton Son Nhut air base before being transferred to our respective units. The buses had the windows covered with wire cages so little kids or adults on Lambrettas could not throw grenades into the open windows. Of losing your friends and comrades to booby traps while Vietnamese farmed the fields. Of being on a sweep and being right behind the platoon radio (RTO) and the platoon leader (a lieutenant) as the RTO steps onto a berm separating the tree line from the rice paddies, where 4 or 5 men had already walked over, and detonating a buried artillery shell. Of later on, stepping out of a tree line over a berm, with the new man right behind me hitting a booby trap on the same ground I had walked over. Of Vietnamese country women, called road girls, practicing the “trade” waiting for the assigned patrol with a combat engineer to clear the re-supply road. Of passing deserted, burned and bombed out hootches and stuccoed buildings splattered with dried globs of napalm. Of suddenly meeting the enemy, and just as suddenly, losing them.

The impressions of Major William Franklin Draper upon entering East Tennessee are called to my mind and I can’t help but think that this is what it must have been like for the Civil War soldier in an enemy’s country as it was for me. Is my experience, putting aside the difference in military technology, any different from the Civil War soldier? Would he have felt the same feelings as I when the buddy he is sitting next to on a forage wagon, is suddenly shot off his seat by a sniper. Would he have felt the same feelings as I in recovering the dead remains of troopers ambushed on an unknown piece of ground? Of looking at the civilians with fear and distrust. If we were to talk, we would have much in common.

PART IV

Guerilla War In West Tennessee: Collective Responsibility

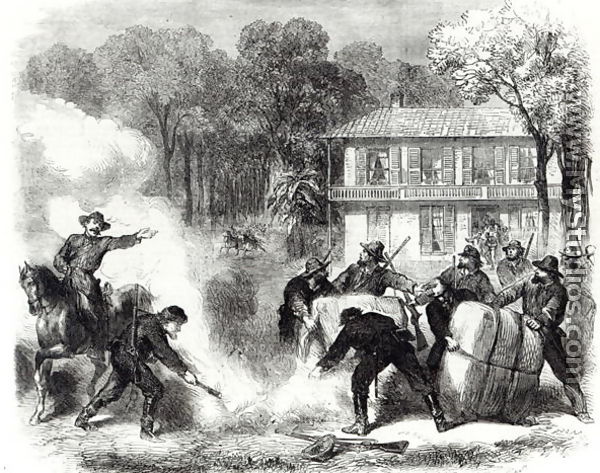

REPUBLIC OF SOUTH VIETNAM, III CORPS, Mekong River

Heard before they were seen, the whop…whop…whop ….whop of UH-1 (Huey) rotor blades slapping the heavy, humid air of South Vietnam, signifies that a helicopter assault is on the way. The rhythmic whine of the turbines belie the loud chopping of the air by the rotor blades outside of the troop compartment even though the side doors are slid back behind the door gunners for quick exit under fire. Nine troop ships, each bobbing up and down in the sultry air currents, nicknamed “Slicks” because they have no appending armaments, only M-60 door gunners on each side, and two heavily armed Huey Cobra gun ships carrying rockets and automatic grenade launchers are going to hit a pre-determined landing zone. If there is no enemy fire in the attempt to land, it is a “Cold LZ”. If there is enemy fire, it is designated over the radios “Hot” to each pilot and aircrew.

This time the landing would be “Hot.” The LZ is near a little hamlet suspected of harboring enemy troops. A light observation helicopter, a LOACH, had been fired at several days before. As the Cobras mark the spot with colored smoke for the lead ship to land, enemy fire suddenly comes up to meet the intruders. The Cobras engage as do the oncoming door gunners from the landing troopships, firing into any mound of vegetation and any tree line suspected of harboring an enemy soldier. All Hell breaks loose. The Hueys quickly hover, unloading their troops, and then are quickly gone. Six infantrymen from each ship, and the command group, quickly move out of the LZ in tactical formation and head for the tree line and the thatched huts of the hamlet. The Cobras provide overwatch, hitting anything that is a perceived threat.

As the platoon nears the hamlet, the enemy melts into the jungle, leaving the old men, women and children to explain to the interpreter, a Kit Carson Scout, i.e., a Viet Cong defector, as to the reasons for the weapons and rice which were unable to be quickly taken away by the withdrawing Viet Cong main force unit. The villagers are quiet, tense and fearful. But there are some who exhibit the tell of controlled anger. This is a hostile village in a free fire zone.

As the platoon nears the hamlet, the enemy melts into the jungle, leaving the old men, women and children to explain to the interpreter, a Kit Carson Scout, i.e., a Viet Cong defector, as to the reasons for the weapons and rice which were unable to be quickly taken away by the withdrawing Viet Cong main force unit. The villagers are quiet, tense and fearful. But there are some who exhibit the tell of controlled anger. This is a hostile village in a free fire zone.

The mission becomes a “Zippo Raid.” Everything will be torched to deny the enemy. As the platoon moves back to a designated LZ for withdrawal, the villagers are taken as well to be extracted for interrogation and resettlement.

No Hearts and Minds are won this day as the helicopters leave behind fire and black roiling smoke where once a little village existed, the occasional burning round “cooking off” into the sky from the ammunition cache discovered and destroyed.

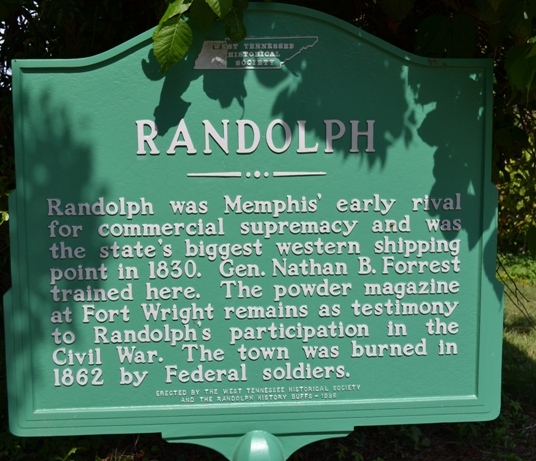

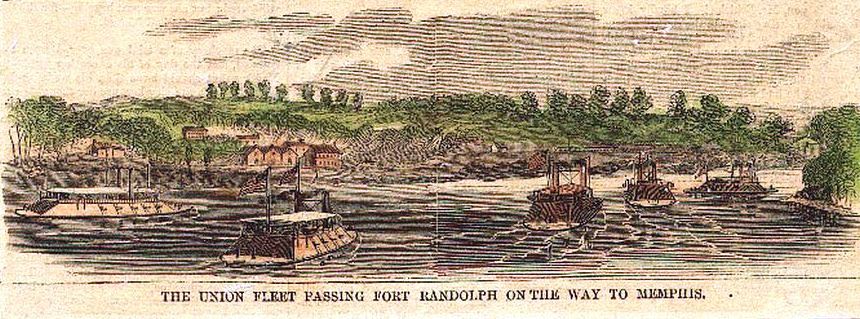

1862 SOUTH BANK MISSISSIPPI RIVER, RANDOLH, TN. (40 River Miles Upriver from Memphis)

The unarmed river packet Eugene is heading down river on September 23, 1862, on its normal run from St. Louis to Memphis. It is loaded with freight and in wartime, a most important commodity to soldiers and citizens alike: mail. It also carries food stuffs and passengers — men, women, and children. Union officers are also aboard. As the Eugene approaches Randolph, once a thriving competitor to Memphis, it is hailed to the river bank. Randolph was the best steamboat stop on the river for taking on cotton because of its location near the Hatchie, but now eclipsed by its more southern rival. It is a shadow of its former self, many buildings, including its warehouses abandoned or falling in and its inhabitants mostly gone. Randolph has less than a 100 inhabitants.

The boat’s Clerk recognizes the man hailing the Eugene and steps off the boat with another man and heads up from the bank to the town. Suddenly, guerillas spring from out of a derelict warehouse and head toward the boat, grabbing the Clerk and another individual along the way. Quick thinking by the ship’s engineer allows the Eugene to push off and slide into the main channel, gathering speed. But not before dozens of bullet holes have left their mark on the pilot house. Thankfully, no one is injured.

Docking at Memphis, the Union officers on board report to the commander of the city. They tell him what has happened. They identify the partisans as approximately 35 men under the command of a reported “Col.” Faulkner. They also tell him that there have been two hostages taken.

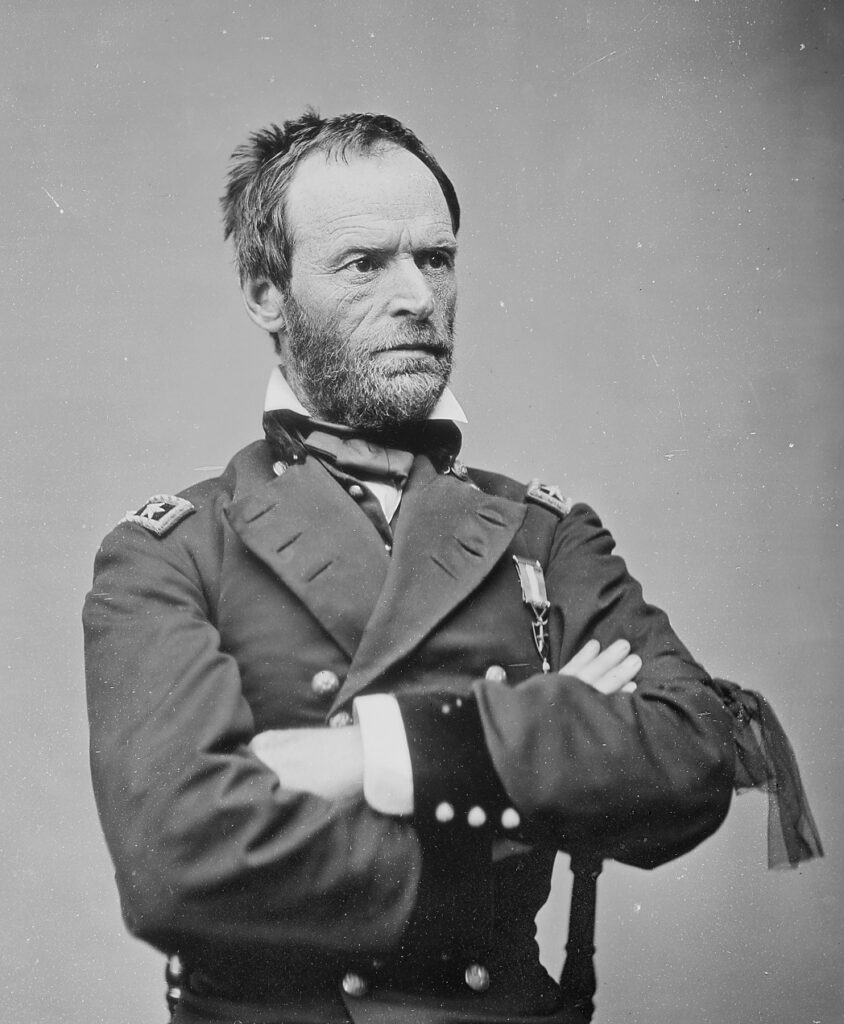

William Tecumseh Sherman is furious. He is barely able to control his mounting anger. He has not been able to quell the hostile populace both inside and outside of the city of Memphis. He will try everything — kindness, reason, arrests of high city and business officials, even hostage taking and sending prominent men off to prison. Nothing has or will work. General Sherman will now show them the consequences of what it means to defy the Federal government and the United States Army. He writes in his correspondence that “I am satisfied that we have no other remedy for this ambush firing than to hold the neighborhood fully responsible, though the punishment may fall on the wrong parties.”

Almost 2 weeks earlier, a forage team guarded by 50 cavalry was fired upon by men believed to be citizens, resulting in one man killed and three wounded. Writing to Halleck, Sherman states that he has sent a strong party to round up 25 of the most prominent men in the vicinity and “each with a horse, saddle, and bridle which I wish to send to LaGrange and there under guard to Columbus by commercial train (to prison).”

Consequently, in the early evening hours of Sept. 25, 1862, the Eugene and Ohio Belle push off from the wharf at Memphis and head upriver to Randolph. Aboard are the 46th Ohio Volunteer Infantry Regiment and a section of artillery under the command of the regiment’s colonel, Charles C. Walcutt. Arriving shortly before dawn, Eugene proceeds past the town to draw fire to ascertain enemy strength. Receiving no fire from the banks, the boat returns and the Ohio Belle and Eugene disembark their assault party. There is no resistance but that does not deter Col. Walcutt from his orders. He is to burn the town, which he does. But Col. Walcutt is also directed to read out General Sherman’s statement apologizing for the raid before firing the town, explaining that the Eugene had been unarmed with civilians onboard and had food and supplies not only for loyal civilians but secessionist families in Memphis as well. The inhabitants of the town would have approximately 3 hours to gather valuables and leave the town. One building would left standing as a warning of future punitive action if attacks on river traffic continue. No guerillas are found after a search of the area. Gen. Sherman writes in is report on September 26, 1862:

“The regiment has returned and Randolph is gone. The town was of no importance but the example should be followed on all similar occasions.”

This will not be the first nor the last incident where boats, both Federal and civilian, will be fired upon on the Mississippi.

After the fall of the river forts — Henry, Donelson — and the destruction or abandonment of the other small forts on the Mississippi, Tennessee, and Cumberland rivers, the way is open for penetration into Mississippi and Alabama. The Confederate Army retreats from Middle and West Tennessee all the way to Corinth, Mississippi to reorganize and to prepare for a counter attack into Tennessee. In April, 1862, that counter attack would be called the Battle of Shiloh (Pittsburg Landing). This battle becomes the largest and bloodiest battle of the Civil War to up to that time. The Confederacy’s western lion, Gen. Albert Sydney Johnston, dies on the field, bleeding to death from an undiscovered wound. As Margaret Mitchell writes in her book Gone With The Wind: “After Shiloh, the South never smiled again.”

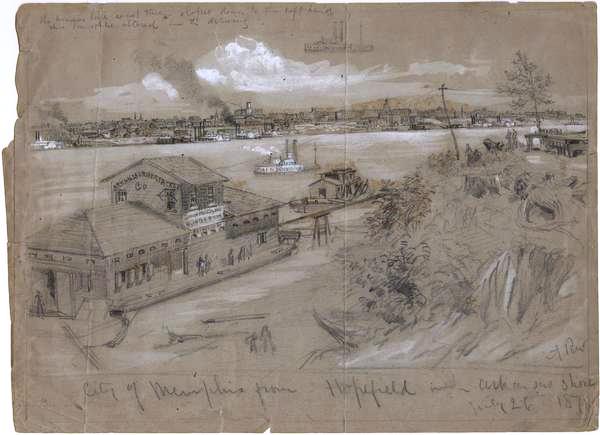

In June, 1862, two months after Shiloh, the small and badly matched Confederate Naval Squadron at Memphis, the perceived protector of the city, is destroyed or captured within two hours by the rams and gunboats of the Union brown water navy as the citizens of Memphis watch in horror from the bluffs. Memphis is delivered into the hands of the Union naval commander, Capt. Charles Davis, by the town’s mayor. But surrender is not in the souls of this pro-secessionist city.

Under Union military command, Memphis fails to prosper. Sherman reports it as a dead city. Many of the men and women of property leave the city rather than submit to Federal control. Some merchants and business owners refuse to take the oath of allegiance as required by Federal authorities and as a result, are not permitted to do business. Society and social gatherings dry up and those that do occur are controlled by Federal authorities. Northern carpetbaggers descend upon the newly conquered area and camp followers of all depiction flood Memphis. Theft, robbery, and prostitution become rampant. Confederate spies and facilitators are everywhere. Memphis becomes the hub of Southern resistance in West Tennessee. Women, passing outside the city, carry supplies to Confederate partisans under their hooped skirts, some carrying weapons of war, some carrying whiskey. Dead animals dying in the city to be buried outside of its limits are opened up, stuffed with supplies, and sewn back up before their journey to their grave to be re-opened and the contraband taken by southern troops.

The population, both in and outside of the city, is hostile. Multiple guerilla bands, cutthroats and thieves, roam the wide plains and timbered river bottoms of West Tennessee, not to mention Confederate cavalry on raids and partisan rangers on bushwhacking forays. A prominent pre-war Memphis Presbyterian pastor, Rev. Edward E. Porter, in 1861 becomes a commissioned officer in the Confederate Army and begins to form his own independent command, “Porters Partisans,” estimated to number in the hundreds if not thousands, who set about burning cotton and destroying bridges. If you were a farmer or a rural citizen, you could be attacked by anyone who desired what you possessed: Union, Confederate, or guerilla; clothes, livestock, money, or possessions. If you were a rural Tennessean, you stayed put, fearful of travelling any distance from your hearth. Hearing many complaints of rural farmers of the depredations of Southern guerillas and to try and halt any such actions by the men under his army command, on November 9, 1862, Grant issues Special Field Order No. 2 at LaGrange, TN that any unit under his command will have pay stoppages assessed to the smallest unit in which the depredation is made and identified.

On November 16, 1862, Grant would enforce the consequences of violating his order against his own men. Special Field Order No. 3 was enacted assessing over $1,200.00 against the men and officers of the 20th Illinois Volunteer Infantry Regt. for breaking into, stealing and damaging goods from several businesses in Jackson, TN, only exempting the men in the hospital or on legal pass. Several officers are ordered mustered out of service for their role or trying to conceal the actions of their men.

Union cavalry is bested at almost every turn by Confederate guerillas who fire on and attack small foraging parties, supply wagons, and even small military units when the numbers are favorable. And when punitive actions are undertaken by larger Federal units, the guerillas simply melt into the local population, their horses being in better shape than the Union cavalry horses worn out from the rigors of campaign. Having no uniform, they can not be identified and rooted out, the local population refusing to identify their kin or neighbors. This was no different than the Vietnamese farmer in the field 160 years later, hiding his Chinese SKS after shooting at an American platoon in a nearby rice paddy the day before. Separating an enemy from the civilian population is almost impossible when the population protects its own out of loyalty or fear.

Sherman, while in Memphis, would write, “There was not a garrison in Tennessee where a man can go beyond the sight of his flagstaff without being shot or captured.”

From the time Gen. Sherman assumes command in Memphis, problems with the citizenry become systemic. When Sherman had been stationed in the pre-war South, he had made many Southern friends. He had a fondness for the South but that affinity would never be returned, and the name of Sherman would become a dreaded and feared name, the same as the name of Hannibal to Republican Romans. Sherman’s reputation would continue to this day. At first Sherman had hoped the war would be as painless as possible on the civilian population, but he would become increasingly convinced instead of protecting and isolating civilians from the results of the conflict, it was the civilians themselves who were the key to ending the war. Making Georgia howl was not about the military. It was about getting the Southern populace to see that the War was hopeless and no longer winnable. Collective Responsibility would be born in Sherman’s mind in West Tennessee. West Tennesseans would yell before Georgians would howl. Sherman would write:

“When one nation is at war with the other, all the people of one are the enemies of the other.”