December 16, 1864

THE CRITICAL ACTION OF THE BATTLE OF NASHVILLE

Above: For many years, this Napoleon 12-pounder faced North at the summit of Shy’s Hill in front of a backdrop of flags representing Minnesota (see story of why BONT flies the Minnesota flag below), the U.S. flag, and the 1st National Flag of the Confederacy. The cannon had to be removed due to weather damage in 2018, and following repairs and refurbishing, was placed at Redoubt No. 1. (Photo by Tom Lawrence)

Above: For many years, this Napoleon 12-pounder faced North at the summit of Shy’s Hill in front of a backdrop of flags representing Minnesota (see story of why BONT flies the Minnesota flag below), the U.S. flag, and the 1st National Flag of the Confederacy. The cannon had to be removed due to weather damage in 2018, and following repairs and refurbishing, was placed at Redoubt No. 1. (Photo by Tom Lawrence)

The Story

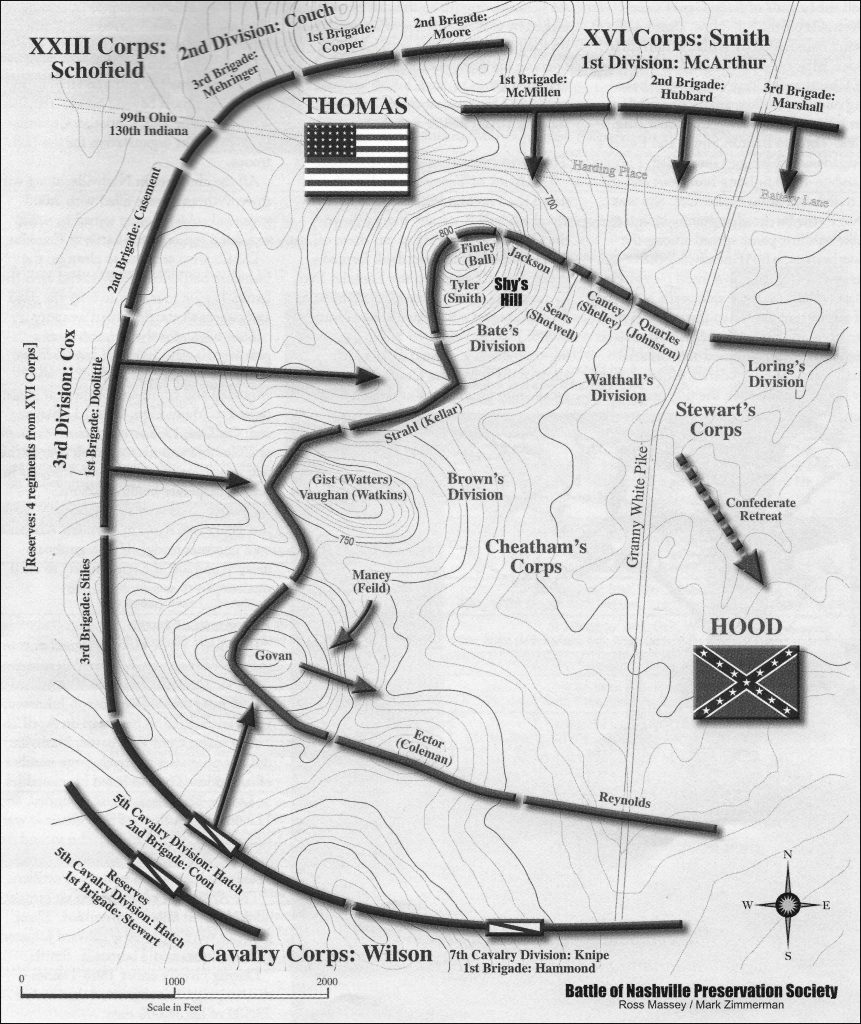

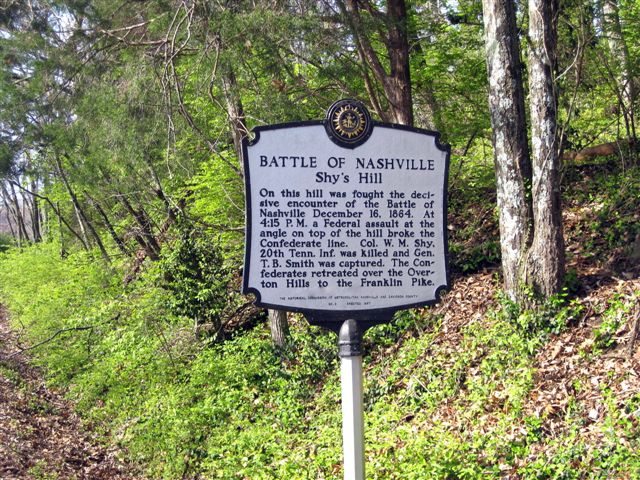

A heavy day of fighting on Thursday, December 15, 1864, saw Confederate forces fall back to the south to an east-west line roughly parallel to the current course of Harding Place in South Nashville. The right flank of the Confederate line was anchored at Peach Orchard Hill to the east, and the left or western flank at Compton’s Hill, later to become known for posterity as Shy’s Hill.

Darkness, battle fatigue and terrain became significant obstacles as Hood’s army attempted to re-group to the south. Depletion from casualties resulted in a considerably shorter defensive line. On the west flank, Hood positioned Maj. Gen. Benjamin Cheatham’s Corps on what he thought would be strategic high ground – the steep promontory of Compton’s Hill. Cheatham, a Nashville native, placed defense of the summit of Compton’s Hill in the hands of Maj. Gen. William B. Bate’s division, consisting (from left to right) of Tyler’s Brigade under the command of 25-year-old Brig. Gen. Thomas Benton Smith, Finley’s Florida Brigade under the command of Maj. Glover Ball, and Jackson’s Brigade commanded by Brig. Gen. Henry Jackson.

Tough Odds for Hood’s Troops. Confederate troops occupying Compton’s Hill did so against staggering odds. They were outnumbered by an overwhelming Union force which had surrounded them with infantry to the north and west of the Hill, and with cavalry to the south.

Above: Artillery piece looking northwest, overlooking Green Hills Shopping Center, Burton Hills and other areas of Southwest Nashville. Federal Troops stormed the Hill from the north and northeast on December 16, 1864. The 12-pounder Napoleon was one of the most prevalent field artillery pieces used by both sides in the Battle of Nashville. BONT placed this replica on the summit in 2008, but had to remove it in 2018 due to weather damage. (Click to enlarge) (Photo by Tom Lawrence)

Serious problems were facing the Confederate force as darkness descended on Thursday evening, December 15. As the first day’s action died down, Cheatham’s Corps had to deal with the combined disadvantages of darkness, muddy terrain, and the weariness of what had been a difficult day on the battlefield, especially on the Confederate left flank.

Cheatham, positioned on the Confederate right flank on December 15, had to move south and west from his position around Nolensville Pike and was late arriving at the high ground. Reestablishing their defenses in the dark created new problems. They dug all night with few tools and axes – a difficult task at night on the steep slope, and were able to cut some trees and pile rock to complement the works. The trenches, however, due either to darkness or miscalculations by the engineers, were inadvertently constructed too far back from the “military crest.” As a result, the steepness of the hill became a liability instead of providing a high-ground advantage, because when daylight came, they were unable to see down the slope far enough from their positions to fire at Federal troops charging up the hill until the attackers were almost in their lines.

In addition, the trench lines were set up by aligning with a fire on the grounds of the Bradford house to the northeast. When daylight came on Friday, December 16, the angle and direction of the trenches did not line up with Stewart’s Corps to the east at around Granny White Pike. An angry Cheatham had to quickly readjust the line to the south in order to link up with the remainder of the Confederate position which ran easterly toward Peach Orchard Hill.

Above: Confederate trench line, marked with head logs, running from the top of Shy’s Hill roughly northeasterly towards Harding Place. (Click to enlarge) (Photo by Tom Lawrence)

Artillery. The conditions also adversely affected the Confederate army’s use of its artillery. U.S. artillery significantly outnumbered Confederate artillery by more than 3 to 1. To make matters worse for Hood’s forces, most of Cheatham’s 34 cannons were unable to get into fighting position on December 16. Unable to get through Granny White Pike, the artillery had to be moved toward the new line across the muddy fields of the Lea Farm. When the fighting resumed on December 16, most of the guns remained bogged down or parked out of position and useless in the area now occupied by St. Bartholomew’s Episcopal Church on Belmont Park Terrace.

Above: Pair of field Howitzers placed on eastern slope, in approximate position of the Confederate artillery on December 16, 1864.

The Confederates were eventually able to place a reduced battery of smoothbore guns on a small plateau on the eastern slope of Shy’s Hill, commanded by Capt. Rene T. Beauregard, son of Gen. P.G.T. Beauregard. The battery initially consisted of smaller and more moveable howitzers, and Maj. Daniel Truehart later supplemented it with four additional smoothbore pieces. Fire from these and a few others were no match for the three Federal batteries which all day raked the top of the hill from the west, north and northwest. Confederate snipers, firing Whitworth long-range rifles, did their best from the high ground, but the prolific Federal fusillade – one battery as close as 500 yards – eventually leveled the earthworks on the summit. By some estimates, as many as 1,500 rounds of artillery shells, many of them from rifled barrels, pounded Compton’s Hill on December 16th.

Above: Map courtesy of Guide to Civil War Nashville, a comprehensive tour guide to the Battle of Nashville sites. Map created by author Mark Zimmerman in conjunction with historian Ross Massey. First published in 2004, the 2nd edition was published in 2019. Click here for more information.

Hood Moves Troops From Hill. As the day progressed, the already depleted Confederate force on the Hill was further reduced by Hood’s perceived need to move troops – four brigades in all — away from the hilltop. The first move occurred around noon, when the encroachment of Maj. Gen. James Wilson’s Union Calvary Corps from the south, behind the Confederate line, required Hood to shift Ector’s brigade of French’s Division, Stewarts Corps, to the south.

Next, furious fighting at Peach Orchard Hill caused Hood to move two brigades of Cleburne’s Division — Lowrey and Granbury — to the right flank in the afternoon. And finally, about the same time, Reynolds Brigade from Walthall’s Division, Stewarts Corps – posted to the right of Bate’s Division on the Hill – was moved south to support Ector. The summit line was left thin, with no reserves.

By late afternoon, with daylight beginning to fade on a rainy day, Federal commanding Gen. George Thomas had been unsuccessful in ordering Maj. Gen. John Schofield to organize an assault on the hill with his XXIII Corps. Growing impatient as the day grew darker, Federal Brig. Gen. John McArthur, division commander in Smith’s XVI Corps, saw the Union advantage gained during the day-long siege of the Confederate left flank slipping away, and that nightfall would enable Hood’s army to either strengthen or escape.

Federal Attack In Late Afternoon. At about 3:30 p.m. he sent a message to Thomas and XVI Corps commander Gen. Andrew Smith that unless he were given orders to the contrary in the next five minutes, his division was going to attack Compton’s Hill and the Confederate line immediately to its east. Receiving no response by his imposed deadline, he ordered the charge by three brigades which contained four regiments of Minnesotans, as well as troops from Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Missouri, Wisconsin, and Iowa.

McArthur began the assault with only the First Brigade. Under the command of Col. William McMillen, they advanced under orders for silence and began the struggle directly up the severe north slope of Compton’s Hill, using the steepness as their cover. The 10th Minnesota Regiment, surging up the northeast side of the hill on the left end of the Union advance, was exposed to flanking fire and was hit hard. As the First advanced half way up the hill, McArthur sent the Second Brigade, with the 9th Minnesota on the right and the 5th Minnesota on the left. Its commander, Col. Lucius F. Hubbard, had two horses shot from under him and sustained a minie ball wound to the neck as the unit crossed a muddy corn field moving southwest. With their line exposed to enfilading fire, they sustained significant casualties including four 5th Minnesota color bearers who were shot down in the charge.

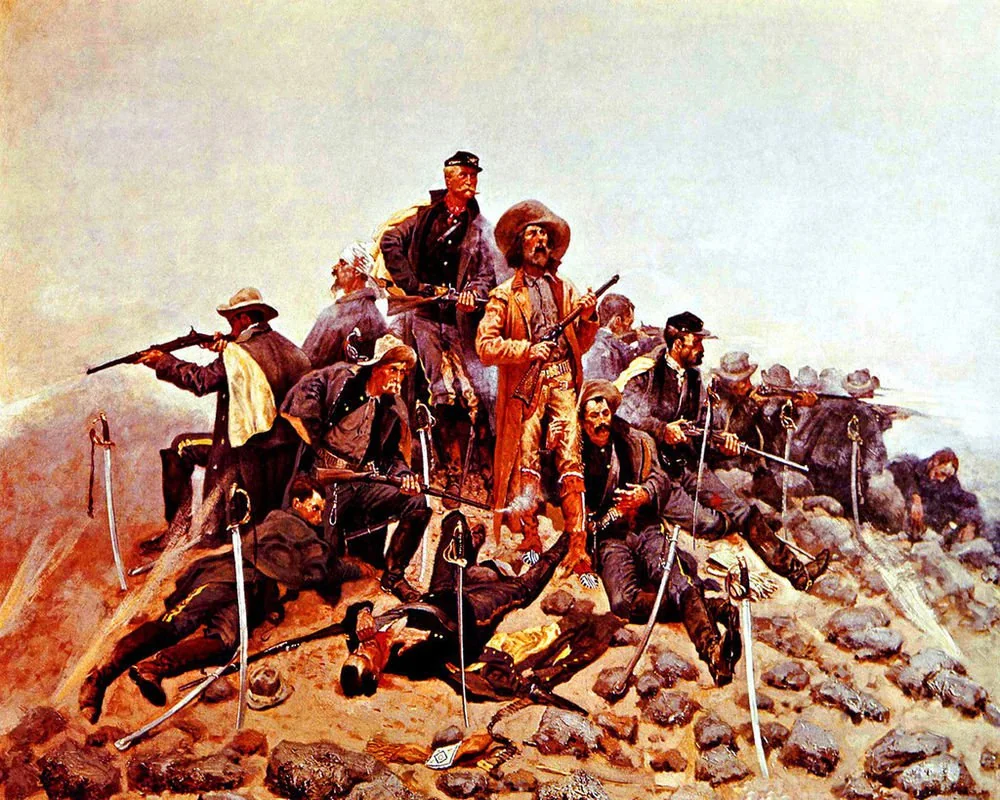

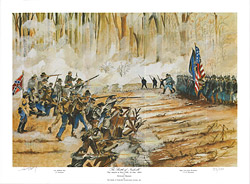

Howard Pyle, a noted 19th century illustrator, painted this mural in 1906. The original is located in the governor’s Reception Room in the Minnesota State Capitol in St. Paul, Minnesota. It depicts the attack on the afternoon of December 16, 1864 by the 5th and 9th Minnesota Infantry Regiments on the Confederate line just to the east of Shy’s Hill, which is seen in the background. The area depicted is just east of Granny White Pike and just south of modern Battery Lane, on modern McArthur Ridge Court.

In short order, however, the 10th Minnesota breached the line of Finley’s Florida Brigade, and attacked Smith’s and Jackson’s Brigades from the rear. This precipitated the Confederate collapse. By the time McArthur’s troops achieved the summit, many Confederates had already begun their retreat toward Granny White Pike and Franklin Pike. Those who remained were captured or killed.

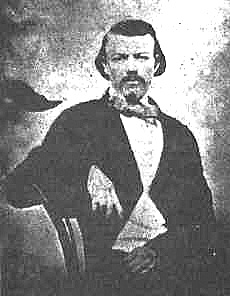

The Fate of Col. Shy and Gen. Smith. Among those who died fighting was 26-year-old Lt. Col. William L. Shy, commanding the 20th Tennessee, under the command of Brig. Gen. Thomas Benton Smith. Col. Shy, who grew up in Williamson County, Tennessee, was

killed by a close range shot to his head. His body was taken to the nearby Felix Compton house and laid on the porch with a blanket over him. His parents came from Franklin to get him. His effort to hold the hill at all cost, and his death on the summit, resulted in a renaming of the hill in his name.

His commander, Brig. Gen. Smith, surrendered, though his fate had an unfortunate end. As he was being led back to Nashville, probably on Granny White Pike, he was struck multiple times on the head by a Federal officer wielding the butt end of a sword. The officer was thought to be Col. William McMillen, who commanded McArthur’s 1st Brigade, though there is no documented proof that he was the assailant. Smith was expected to die from the resulting skull fractures; he survived, but was institutionalized for the remainder of his life at an asylum in Nashville. The street on which the Shy’s Hill trailhead begins, and where the historical marker is located, is named in his honor: Benton Smith Road.

The fall of the Confederate left flank at Shy’s Hill marked the end of the battle of Nashville. Even though the right flank had held its line in the battle at Peach Orchard Hill to the east, the entire force broke with the collapse of the west and the battle of Nashville ended with the retreat of Hood’s Army toward Brentwood and Franklin.

Shy’s Hill Now. Today, the Battle of Nashville Trust owns a portion of Shy’s Hill and leases the summit from the Tennessee Historical Society. It is protected by a conservation easement through the Land Trust For Tennessee. The kiosk, eastern slope trail, and Memorial flag plaza at the summit were placed by, and are maintained by, BONT.

The role of the Minnesota troops at Shy’s Hill and in the Battle of Nashville is memorialized in various ways, including a Minnesota monument at the National Cemetery in Nashville. On Shy’s Hill, BONT flies the Minnesota state flag to recognize the fact that Minnesota sustained more casualties at Nashville than at any other battle in which its men fought, and that they played pivotal roles during both days of the Battle of Nashville.

The best-known painting depicting the battle at Shy’s Hill is the famous Howard Pyle canvas located in the Minnesota state capitol. For an in-depth look at the role of Minnesota in the Battle, including the Pyle painting, see Minnesota Regiments At Nashville written by John Allyn, former president of BONT.

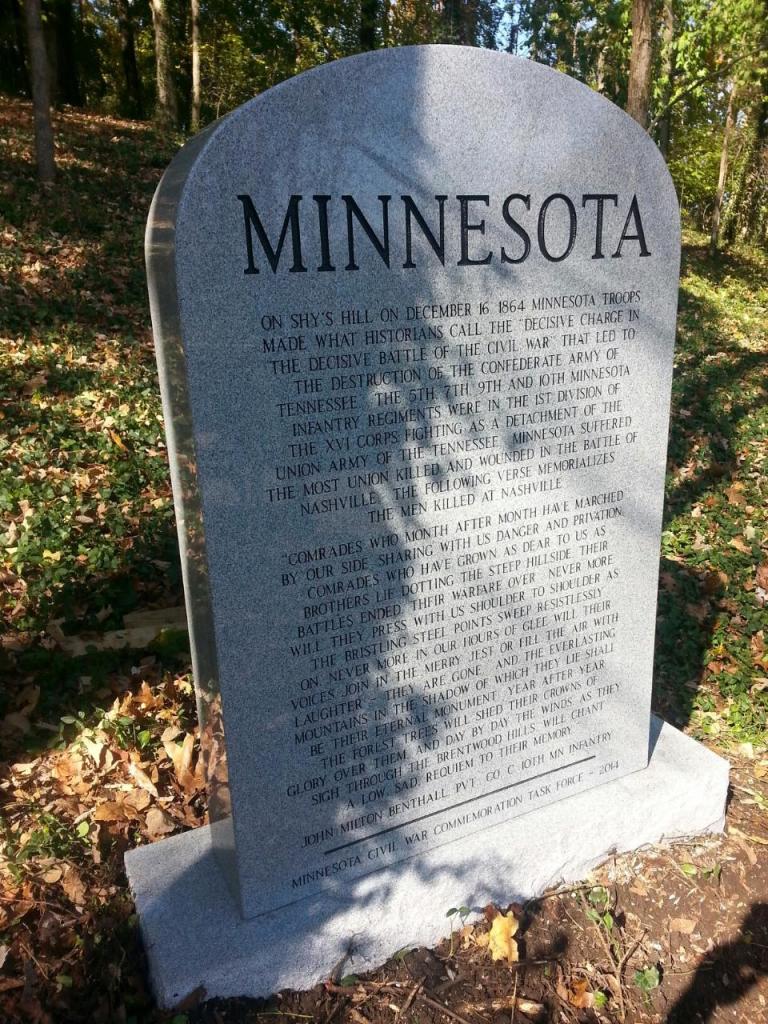

As part of the Sesquicentennial commemoration, the Soldier Recognition Committee of the Minnesota Civil War Commemoration Task Force, in conjunction with BONT and The Land Trust of Tennessee, erected a granite monument on the northeastern slope of the Hill which had been traversed by charging Minnesota troops in the battle. For more detail, see separate story below or click on the Sesquicentennial page tab on this website.

In October, 2023, a granite monument commemorating the 114th Illinois Regiment was dedicated on the plateau near the Minnesota monument. The 114th had been involved in overrunning Redoubts 4 and 5 on Dec. 15, 1864, and was in the charge up the north slope of Shy’s Hill the next day, being the first to gain the works and break the line at Finley’s Florida brigade on the summit. See story below for more detail.

Visiting Shy’s Hill:

Directions. Shy’s Hill is located off Benton Smith Road in South Nashville. From I-440, exit south on Hillsboro Road and travel south to Harding Place. Turn left onto Harding, then turn right onto Benton Smith Rd. to the historical marker about 100 yards from Harding Place. NOTE: There is no entrance to Shy’s Hill memorial area from Shy’s Hill Road on the west side of the Hill. For a Google GPS map to the trailhead, which is marked by the historical marker and an interpretative kiosk at the bottom of the hill, click this Google link.

Admission. Free to the public. The site is open from dawn to dusk. Parking space is minimal; large vehicles may not be feasible.

Monuments and related structures. An interpretative kiosk with maps and summary of the battle is at the trail-head. A trail leads up to the summit, which is marked by a memorial flag plaza and has vistas during winter months of the surrounding areas from which the Federal assault occurred in the late afternoon of December 16, 1864. On the low northeastern plateau of the hill, BONT has placed two Howitzer artillery pieces located approximately where Confederate artillery was in action. Near the guns is a Monument honoring the Minnesota troops who died in the assault of the hill.

Special reminder to our visitors. BONPS asks each visitor to remember that Shy’s Hill is a historic Civil War field of battle, and therefore, is “hallowed ground” on which men of the Union and Confederacy died on December 16, 1864. Please honor and respect their memory, the battlefield grounds on which they fought, and the historical significance of the event that occurred here when you visit.

Metal detecting and related activity. The possession and use of metal detectors for the purpose of relic hunting on Shy’s Hill property, as well as theft or damage relating to its structures and monuments, are strictly prohibited and violators will be prosecuted. Area surveillance includes video monitoring.

February, 2023

NEW TRAIL TO THE SUMMIT MAKES SHY’S HILL MORE ACCESSIBLE TO ALL VISITORS

The Battle of Nashville Trust has completed construction of a new, revised trail up to the top of Shy’s Hill and it is now ready for visitors.

The new design features updated steps up to the trailhead, a specialized stone surface that removes obstacles such as tree roots, and a newly plotted route up the steep slope that makes the climb easier.

For all of the years the Trust has had ownership or control of the Shy’s Hill battleground, maintaining a safe and accessible trail to the top has always been a challenge due to the extreme elevation angle. In an attempt to finally correct that problem, BONT president Bill Ozier said the Trust retained the services of the Atlanta trail-design firm, “Tailored Trails,” which is also rebuilding the walking trails in Nashville’s Percy Warner Park. The trail surface is designed to withstand water erosion to the greatest extent possible on extreme grades like Shy’s Hill.

For all of the years the Trust has had ownership or control of the Shy’s Hill battleground, maintaining a safe and accessible trail to the top has always been a challenge due to the extreme elevation angle. In an attempt to finally correct that problem, BONT president Bill Ozier said the Trust retained the services of the Atlanta trail-design firm, “Tailored Trails,” which is also rebuilding the walking trails in Nashville’s Percy Warner Park. The trail surface is designed to withstand water erosion to the greatest extent possible on extreme grades like Shy’s Hill.

BONT also had a gravel pad built for the most recent monument addition to the Hill, representing and honoring the 114th Illinois Infantry which was involved in the battle of Dec. 16, 1864, and suffered casualties in the assault on this high ground.

President Ozier stressed that BONT’s board and Shy’s Hill team are working on plans to erect a granite monument at the summit, honoring the various Confederate units that defended the hilltop against the overwhelming Union forces arrayed below it.

Later in 2023, the two “Mountain Howitzers” that were originally installed on one of the lower plateaus of Shy’s Hill will be returned to their place near the new trail. The two smoothbore 12-pounder replicas were removed in 2022 to be refurbished and repaired from weather damage.

October, 2023

MONUMENT DEDICATED ON SHY’S HILL TO COMMEMORATE 114th ILLINOIS VOLUNTEER INFANTRY

Representatives of both the “114th Regiment, Illinois Volunteer Infantry Reactivated” and the Battle of Nashville Trust (BONT) formally dedicated placement of a granite monument on Shy’s Hill on Oct. 28, 2023, in honor of the men of the 114th Illinois who took part in the assault of the Hill on Dec. 16, 1864.

Pictured above, Left to right, women: Mary Disseler, Stephanie Thomas, Lisa McLane, and Laura Reyman. Men: Stan Buckles, Don Ferricks, Jonathan Reyman, David Jostes, Andy VanDeVoort, Violet Filipiak (in front of Andy, her grandfather), Mike Vizral, Shawn McLane, Richard Schachtsiek, Lisa McLane, and Laura Reyman. Photo by Bobby Whitson

Pictured above, Left to right, women: Mary Disseler, Stephanie Thomas, Lisa McLane, and Laura Reyman. Men: Stan Buckles, Don Ferricks, Jonathan Reyman, David Jostes, Andy VanDeVoort, Violet Filipiak (in front of Andy, her grandfather), Mike Vizral, Shawn McLane, Richard Schachtsiek, Lisa McLane, and Laura Reyman. Photo by Bobby Whitson

The Illinois monument, erected on the Hill in February, 2023, by the Illinois group with cooperation of BONT, is the second one honoring Federal troops involved in the battle at Shy’s Hill. In November, 2014, a granite monument was placed on the plateau of the Hill by the Minnesota Civil War Commemoration Task Force in memory of the 97 Minnesota troops killed in the charge up the north and northeastern slopes.

Andy VanDeVoort and his granddaughter, Violet Filipiac, sound taps in echo. To hear them, click their photo

The Federal monuments will be joined in the future by an obelisk style monument at the summit honoring the Confederate forces which held the Hill on the evening of Dec. 15 and most of the day of Dec. 16. (BONT uses Peffen Cline Masonry Group for monument installation due to the high level of expertise needed on the Hill’s challenging terrain.)

The dedication ceremony included members of the 114th Illinois Reactivated dressed in period uniforms with comments by several of their representatives including Col. Richard Schachtsiek, Stan Buckles, and Chaplain Jonathan Reyman, as well as by BONT president Bill Ozier and historian Jim Kay. In addition, taps were sounded in echo by Illinois bugler Andy VanDeVoort and his granddaughter, Violet Filipiak, and a commemorative wreath was placed at the site by Shawn McLane on behalf of the 114th, Donald Ferricks on behalf of the descendants of the original 114th, and Mary Disseler on behalf of the Soldiers Aid Society.

The Illinois contingent included Stan Buckles of Mt. Pulaski, IL, the representative of the 114th Regiment Reactivated who worked with BONT regarding installation of the monument. He has written a regimental history of the unit entitled “Not Afraid To Go Any Whare,” quoting a line from a soldier’s letter.

The original 114th Regiment was formed in the summer of 1862. The unit was unique in that most of its members, or their families, personally knew President Abraham Lincoln, causing their remarks in letters and diaries to take on a more familiar tone when writing of President Lincoln.

Most of the regiment’s early action was in Mississippi, including the Battle of Jackson and the siege of Vicksburg. However, at the battle of Brice’s Cross Roads in North Mississippi, due to poor leadership by commanding Gen. Samuel D. Sturgis, the regiment was decimated by Gen. Nathan Bedford Forrest in June, 1864. Stan Buckles noted that after that embarrassment, several members of the 114th testified in a later Court Of Inquiry against the drunken conduct of both Sturgis and their brigade commander, Col. William L. McMillen. As noted below, this name would come to play an important but dishonorable role in the Battle of Nashville, according to many historians.

The Regiment fought in the Battle of Tupelo, Mississippi in July, 1864 before arriving in Nashville as part of Gen. Andrew J. Smith’s XVI Corps, Brig. Gen. John MacArthur’s 1st Division. The 114th was one of three regiments in the 1st Brigade (along with the 93rd Indiana and 10th Minnesota) still under the command of the widely disliked and disrespected Col. McMillen.

When the Battle of Nashville began on Dec. 15, 1864, the 114th Illinois was involved in the capture of both Redoubts 4 and 5 on Dec. 15. Late in the day of Dec. 16, 1864, they were among the large surge of Federal troops who successfully participated in the charge up Compton’s (now Shy’s) Hill. They were one of the first regiments to gain the north slope works and break the Confederate line of Finley’s Florida brigade at the summit.

As the battle at Shy’s Hill came to an end, Confederate Brig. Gen. Thomas Benton Smith was forced to surrender and shortly thereafter, while in custody and defenseless, he was bludgeoned over the head with a sabre by a Union officer, causing permanent brain damage that left him disabled for life. Col. McMillen has been alleged to be the assailant, as noted by some historians, but there is no official record of the attacker’s identity. If McMillen was the assailant, he had long since lost the respect of the men of the 114th Regiment. The street that is adjacent to the eastern slope of Shy’s Hill is named “Benton Smith Rd.” in Smith’s honor.

Above: Men of the 114th accompanied by members of the Battle of Nashville Trust Board, including L-R, Jim Kay, Bobby Whitson, Sidney McAlister and Bill Ozier.

The 114th Regiment, Illinois Volunteer Infantry Reactivated, was founded only three years after the Civil War Centennial in 1968, and has been continually active since its founding. It celebrated its 50th anniversary in September, 2019, making it one of the oldest reenactment/living history Civil War regiments in the country. Their goal is to place markers on all of the battlefields in which the unit saw action, and have already done so at Brice’s Cross Roads and now, Shy’s Hill.

See additional photos (courtesy of Bobby Whitson and Sidney McAlister) of the Ceremony in the gallery below (hover cursor over photo for full captions):

- Stan Buckles addresses attendees during dedication

- Richard Schachtsiek speaking

- Men of the 114th Illinois Infantry Reactivated

- Andy VanDeVoort and granddaughter Violet Filipiak sound Taps

- Dedication Ceremony in progress

- Bill Ozier remarks at wreath placement

- BONT representatives Philip Duer, Jim Kay, Bobby Whitson, Bill Ozier and Sidney McAlister

- Jim Kay watches Taps played at Howitzer battery

- Representatives of Illinois and Nashville contingents

- Group portrait of 114th

- See names in main story

October, 2023

SHY’S HILL ARTILLERY BATTERY READY FOR ACTION AS REFURBISHED HOWTIZERS RETURN TO PLATEAU

Two Mountain Howitzers that had been removed from Shy’s Hill a year ago for repair were reinstalled at their historic location on the Hill on Oct. 14, 2023, after refitting and restoration by specialists in Pennsylvania.

Mountain Howitzers return to the plateau on Shy’s Hill as Mark Martin and Bobby Whitson begin removing shipping material. Photo by Bill Ozier

The guns symbolize the howitzers that were wrangled up to this spot through darkness and muddy fields after the first day of the Battle of Nashville on Dec. 15, 1864, by the men of Confederate Capt. Rene Beauregard’s artillery battery. For a more complete summary of the acquisition and history of these field pieces, see earlier posts below.

The reinstallation was accomplished by Jim Kay, driving a 4-wheeler, along with BONT President Bill Ozier, Board member Bobby Whitson, and former Board member Mark Martin.

Mark Martin (L) and Bobby Whitson (R) assist Jim Kay on 4-wheeler to move howitzers into place. Mules and horses, not ATVs, were used in 1864. Photo by Bill Ozier

In addition, the 6-pounder field piece donated by the Woolwine family was also delivered back to BONT after being refitted with a new aluminum carriage. The cannon is destined to take its place on the battery line at Redoubt No. 1.

The reproduction cannon tube was donated by Ms. Graham Woolwine-Gilson, a Nashville native now living in Mamer, Luxembourg, and bears a bronze plaque stating, “Donated in memory of Porter Anthony (Tony) Woolwine.” The replica cannon tube was designed to resemble those manufactured by Noble Brothers, a large ironworks factory in Georgia producing pre-war items such as steam boat engines and locomotives but which turned some of its production to cannons for the Confederacy during the Civil War.

For a more detailed summary of the tube and its acquisition, see separate story at the Battle of Nashville “News” page.

Sept. 17, 2022

SHY’S HILL HOWITZERS REMOVED FOR REPAIR AND REFITTING WITH NEW WEATHER RESISTANT CARRIAGES

The two “Mountain Howitzers” located on the lower east side of Shy’s Hill were removed by BONT board members on Sept. 17, 2022, after the replica field pieces became too weather-damaged to be appropriate for display, and will be returned after repairs.

The two replica mountain howitzers were placed on the Hill in April, 2019, to demonstrate the approximate location of the only artillery pieces that were in service there on Dec. 16, 1864. However, wood used in construction of the carriages had deteriorated, requiring their removal.

Howitzer tubes and broken carriages loaded aboard BONT board member Bobby Whitson’s much-used “ol’ warhorse Bessie” for transport to repair facility

“With the leadership of Bobby Whitson, chainsaw work by Jim Kay, strong backs of Clay Bailey, Jim Atkinson, Jimmy Pickel, and the assistance of gravity, we were able to decamp the two artillery pieces from the slope of Shy’s Hill! We look forward to their return with new carriages,” said BONT president Bill Ozier, who was also on the work detail.

BONT will have the cannon barrels refurbished and refitted with aluminum carriages, and they will be returned to the site as soon as possible. The location was determined by BONT historians to be the most likely area where Hood’s troops were able to assemble a small battery of artillery during the night of Dec. 15 and early morning hours of Dec. 16, 1864.

After the Confederate line was forced to fall back from its initial positions on Dec. 15, 1864, Maj. Gen. Benjamin Cheatham’s corp had only 34 artillery pieces available for service for the second day of battle, and only a handful of these could be transported through the night and the boggy cornfields to a flattened plateau on the east side of the Hill. Maj. Gen. William Bate had apparently found a rough country road in this flattened area, believed to be located in the vicinity of the current Benton Smith Rd. and the Shy’s Hill trail head.

After the Confederate line was forced to fall back from its initial positions on Dec. 15, 1864, Maj. Gen. Benjamin Cheatham’s corp had only 34 artillery pieces available for service for the second day of battle, and only a handful of these could be transported through the night and the boggy cornfields to a flattened plateau on the east side of the Hill. Maj. Gen. William Bate had apparently found a rough country road in this flattened area, believed to be located in the vicinity of the current Benton Smith Rd. and the Shy’s Hill trail head.

By first light on Dec. 16, the Shy’s Hill battery, which was under the command of Capt. Rene T. Beauregard, had been supplemented on the plateau with four other field pieces under the command of Maj. Daniel Truehart. Many others, especially the heavy Napoleons, could not be dragged through the thawing mud of the fields, especially under the difficult conditions of a nighttime retreat and establishment of a new line of battle.

The “Mountain Howitzer” was a bronze smoothbore 12-pounder field piece that got its name from its development in the 1830s as an easily transportable field piece for use in the western mountain terrain of the Indian and Mexican-American wars. It was much more portable than the larger artillery such as the 2,500 pound Napoleons, the workhorse artillery of the Confederate army. The howitzer was relatively lightweight and could be disassembled into three pieces for easier transportation. It fired explosive ordnance as well as case and canister, with a maximum range of about 1000 yards.

THE LIFE, DEATH, AND MYSTERY OF COL. WILLIAM SHY

Shy’s Hill, preserved and maintained by the Battle of Nashville Trust, is by far the most iconic bloodstained combat ground of the Battle of Nashville.

Shy’s Hill, preserved and maintained by the Battle of Nashville Trust, is by far the most iconic bloodstained combat ground of the Battle of Nashville.

However, due to its proximity to the home of Felix Compton, it was known only as Compton’s Hill on December 16, 1864, when the vicious clash occurred there late on a frigid, rainy afternoon that resulted in the demise of the Army of Tennessee.

The Hill rose to prominence for several reasons, including its towering physical presence on the Nashville landscape, the historic uphill charge by Minnesota troops as light was fading, and its fate as the site of the breach in the Confederate line that ended the battle. But it got its name from a 26-year-old Tennessee officer, Col. William M. (Mabry) Shy, who had stood his ground on the summit until his death.

Shy was born in Bourbon County, Kentucky, one of 10 children, but at the time of the Civil War had been living about 15 miles south of Compton’s Hill at Two Rivers Farm in Franklin, Tennessee. He had joined the other 880 members of the 20th Tennessee Infantry Regiment when it was organized on June 12, 1861, at Camp Trousdale in Portland, Tennessee. As a member of Co. H, he had risen swiftly through the ranks from private to colonel under the command of Brig. Gen. Thomas Benton Smith.

Whittled down to a fraction of their original number by the time they got to Nashville, after fighting in some of the toughest fields of battle in the South for more than three years (including Shiloh, Murfreesboro, Missionary Ridge, Atlanta and Franklin), the 20th Tennessee was held in reserve, and had not seen action, on the first day of the Nashville conflict. On Dec. 16, however, Gen. John Bell Hood placed them front and center atop Compton’s Hill.

After the massive late-day charge by Federal troops, reports indicated that the top of the Hill was strewn with dead and wounded. The body of Col. Shy was among the dead, shot in the forehead at point blank range (powder burns were recorded), the ball exiting at a downward trajectory. A family member reported that his body was found unclothed and pinned to a tree by a bayonet, but the accuracy of this fact is disputed, and later scientific examination of his body did not reveal any such wounds.

Above: Felix Compton house, circa 1973. Built in the 1840s and known locally as “Seven Hills,” the home was held by the Comptons until 1905, and was eventually sold in 1929 to Nashville insurance executive A.M. Burton. Located on an expansive estate anchored at the corner of Harding Place and Hillsboro Road, the property was eventually gifted by the Burton family in the 1980s to David Lipscomb College, which sold it to a developer who transformed the land into the Burton Hills residential and commercial complex. Photo: Nashville Public Library Digital Collection

Compton Hill was part of Felix Compton’s 750 acre farm and the family home was in the midst of the battle on Dec. 16, 1864. After the fighting that evening, the house was used as a field hospital for both sides. Emily Compton was one of Felix Compton’s daughters and was at the house during the battle and its immediate aftermath. In 1912, as Mrs. Emily C. Thompson of Birmingham, she submitted an article in Confederate Veteran Magazine, (Vol. XX, November, 1912, No. 11, p. 522-23), in which she confirmed Col. Shy’s body had been placed on the front porch of the Compton house, which was less than a mile northwest of the Hill:

“From the windows of our home I watched the campfires of our boys all night of 15 December. They were camped in my father’s hills and the hills of my great uncle, Harry Compton, between the Granny White and Hillsboro Pikes. The next day our line gave away and passed on to the south. There were 150 dead and wounded in our home at one time, so I was told. . . . Colonel Shy fell on the afternoon of December 16. His body, with many others of both armies, was laid upon the front gallery of our home. Shortly afterwards a Federal guard called my attention to Colonel Shy. Then turning back from the face a gray blanket which some kind friend had placed over the body, I saw him as he lay so peacefully there with that cruel hole in his brow.”

There is at least one family report that the parents recovered “Bill’s” remains from the hilltop, but the Compton home appears to be more probable from Mrs. Thompson’s report. Col. Shy’s parents, whose sympathies were split between North and South, were notified of his death but the roads were too dangerous for them to risk traveling north to Nashville to retrieve the body. They were able to get help from Dr. Daniel B. Cliffe, whose wife Virginia was driven by horse-drawn wagon to the battlefield. Dr. Cliffe had been a surgeon attached to the 20th Tennessee Regiment. The body was returned to Two Rivers farm where it was embalmed, reportedly by Dr. Cliffe, and buried in an expensive cast-iron coffin under a stone marker that read:

COL W.M. SHY

20TH TENN.

INFANTRY C.S.A

BORN MAY 24, 1838

KILLED AT BATTLE OF

NASHVILLE

DEC. 16, 1864

Above: Photo of Col. Shy’s grave marker at Two Rivers Farm, which is privately-owned property on Del Rio Pike near Franklin. Photo by John Banks.

Col. Shy’s saga did not end there, however. In one of Tennessee’s most bizarre historical events, the gravesite was vandalized in 1977. Law enforcement officials called to the scene found a headless body as well as the 300-pound iron coffin which had been heavily damaged. Initial investigation was that the body was of a recent unidentified victim of homicide. But Dr. William Bass, a noted forensic anthropologist from the University of Tennessee known for his studies into human decomposition, was brought in to investigate the remains, and the final conclusion pointed to the identity of the body as that of Col. Shy, unearthed by grave robbers who were never identified or arrested.

On Feb. 13, 1978, Mrs. W.J. Montana, the great-great granddaughter of his brother (Col. Shy was never married), travelled from Texas for the reinterment on Two Rivers Farm on Del Rio Pike in Williamson County (See photo of Two Rivers Mansion at left). The casket was donated to the Carter House Museum in Franklin.

On Feb. 13, 1978, Mrs. W.J. Montana, the great-great granddaughter of his brother (Col. Shy was never married), travelled from Texas for the reinterment on Two Rivers Farm on Del Rio Pike in Williamson County (See photo of Two Rivers Mansion at left). The casket was donated to the Carter House Museum in Franklin.

One of the most complete accounts of Col. Shy’s life, death, disinterment, and re-burial, can be found in the booklet The Pillaged Grave of a Civil War Hero by John T. Dowd, published in 1985. The book is for sale by BONT but currently sold out. To read its contents on line, click here.

BONT board member, Facebook editor and Civil War author John Banks took a bicycle tour of Civil War sites in Middle Tennessee that included the Two Rivers Farm and Shy grave in 2020. Ride along with John as he explores these sites in his HistoryNet.com story, “Pedal-Powered War Tour.” Many of the photos in this story are his, and some are from the extensive collective of BONT President Jim Kay, whose lecture presentations on the life of “Billy” Shy shed light on this significant Battle of Nashville figure.

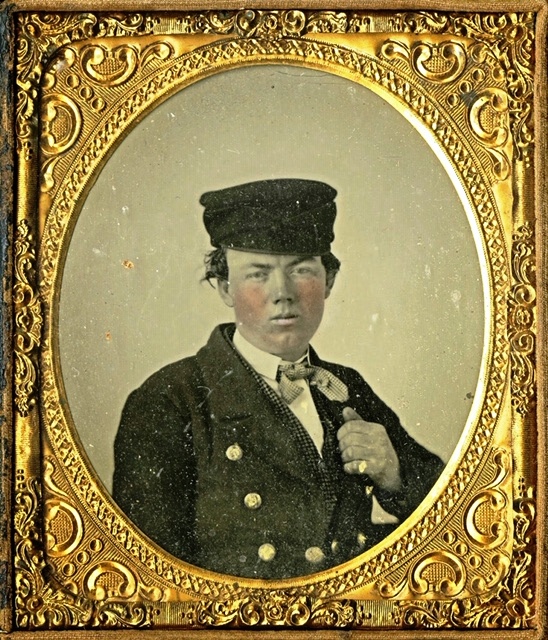

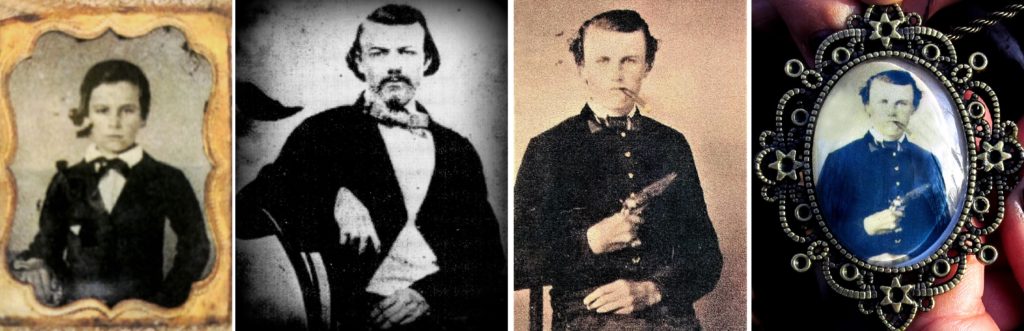

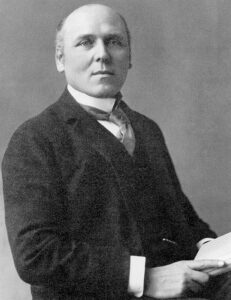

Above, images of William “Bill” Shy

December 16, 2017

SHY’S HILL RECEIVES VISIT FROM ITS NAMESAKE’S DESCENDANTS

At the 153rd anniversary of the battle on Dec. 16, 2017, one of Col. William Shy’s descendants made a special visit – her first ever –to the Hill which, due to the conspicuous courage and ultimate death of her 26-year-old ancestor, was renamed Shy’s Hill for posterity.

At the 153rd anniversary of the battle on Dec. 16, 2017, one of Col. William Shy’s descendants made a special visit – her first ever –to the Hill which, due to the conspicuous courage and ultimate death of her 26-year-old ancestor, was renamed Shy’s Hill for posterity.

Linda Whitson told interested visitors at the Hill that she is the great, great niece of Col. Shy. She and her husband Frank had driven down from their home in Russell Springs, Kentucky, to spend a “family history” weekend in Middle Tennessee, visiting the small family cemetery at Two Rivers farm near Franklin where Colonel Shy had been interred, and climbed up her ancestor’s famous Hill to see the place where he had died defending that ground 153 years earlier.

Ms. Whitson was wearing a pendant which encased a seldom-seen photograph of her ancestor. In the photo, he appears to be enjoying a cigar and holding a pistol across his chest.

The two videos below feature BONT President Jim Kay and retired Lt. Col. James P. Reese, a 25-year Army veteran who served with distinction with the elite special ops unit Delta Force, discussing military aspects of the Confederate defenses of Shy’s Hill, including the trench line and military crest issue on the northeastern slope, and the use of artillery on the east side of the Hill.

Above: Trail-head kiosk contains interpretative maps, photos and descriptions of the battle at Shy’s Hill. (Photo by Tom Lawrence)

Above: Memorial Flag Plaza on the summit, showing Memorial Wreath placed each December 16 by descendants of men who fought on this ground for both the Union and the Confederacy. (Click to enlarge) (Photo by Tom Lawrence)

Above: Donors Plaque at the Shy’s Hill trail head, bearing the names of those who contributed to the purchase the site for BONT in 2008. (Click to enlarge) (Photo by Tom Lawrence)

HOWARD PYLE’S FAMOUS MURAL OF SHY’S HILL

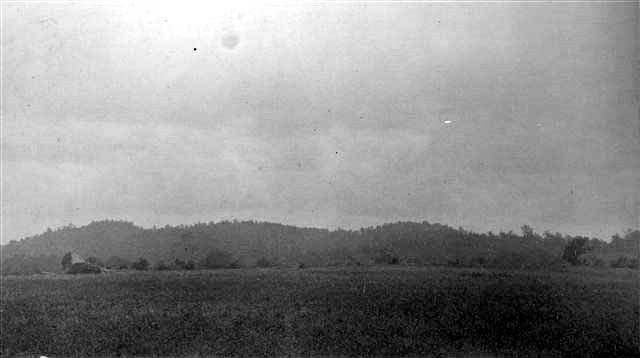

The Federal attack on Shy’s Hill was the most iconic action of the Battle of Nashville. There are no contemporaneous photographs of that part of the battlefield, but we are fortunate that Minnesota artist Howard Pyle visited the area before completing his Shy’s Hill painting in 1907. After researching the terrain and taking photos, he returned to Minnesota to complete his massive mural on display in the Minnesota State Capitol.

Below are two articles by Battle of Nashville Trust board members, analyzing and discussing various aspects of the painting. John Banks explores the controversies that developed after the painting was completed, as well as pondering the potential treasure trove of Pyle’s missing photos. Philip Duer explores the accuracy and substance of the painting from the standpoint of an artist/historian.

December, 2020

DID HOWARD PYLE GET IT WRONG? AND WHERE ARE HIS PHOTOS?

BONT board member and Civil War blogger John Banks has made some interesting discoveries about the famous Howard Pyle painting of the battle at Shy’s Hill on December 16, 1864. Though the painting remains the best depiction of the charge at Shy’s Hill, it isn’t without controversy.

Above: Photo courtesy of Betsy Haag of the 5th Minnesota Research Group on Facebook. (https://www.facebook.com/groups/5thMNResearch)

Pyle was a Minnesota artist who, in 1906, completed a huge six-by-eight foot oil painting of the Minnesota troops charging the Confederate lines positioned on Shy’s Hill and stretched along what is now Harding Place/Battery Lane. The painting hangs in the governor’s reception room of the Minnesota Capitol building. At the time, Pyle was an internationally-known illustrator and author, with a reputation for carefully researching his subjects in order to provide accurate detail in his illustrations which appeared in thousands of books, magazines and other publications.

What John Banks discovered is that the Pyle’s painting was not met with universal approval by some Federal soldiers who were actually involved in the attack. In interviews with a Minneapolis newspaper in 1906, some said they felt the topography was incorrect, and others were apparently miffed that some regiments were left out of the painting. Before his death in 1911, Pyle defended the accuracy of his rendering. As John Banks found out, Pyle, as usual, had done his homework: he had visited the Nashville battlefield in preparation for the painting, and took a number of large photographs.

Read the details in John’s insightful blog, “Where are Howard Pyle’s ‘Lost’ Nashville battlefield photos?”, by clicking HERE. Click the links below to open PDFs of the two articles in the Nov. 6 and Nov. 19, 1906, editions of the Minneapolis Journal newspaper in which the aging vets took issue with the painting.

Minneapolis Journal Nov. 6, 1906

Minneapolis Journal Nov. 19, 1906

For further discussion of the pivotal afternoon attack by the Minnesota troops, see the in-depth article by former BONT President John Allyn by clicking the Features page on this website.

August, 2023

HOWARD PYLES’ PAINTING OF THE BATTLE OF NASHVILLE

What’s Right, What’s Not, and What it Portrays

An Opinion: By Philip Duer

Howard Pyle finished “The Battle of Nashville” in 1907. The painting was commissioned by the Minnesota State Architect to portray the battle in large scale. It hangs in the Governor’s Reception Room in the state capitol at St. Paul. The painting was to commemorate the battle because Minnesota lost more soldiers at Nashville than in any other battle during the Civil War.

Howard Pyle finished “The Battle of Nashville” in 1907. The painting was commissioned by the Minnesota State Architect to portray the battle in large scale. It hangs in the Governor’s Reception Room in the state capitol at St. Paul. The painting was to commemorate the battle because Minnesota lost more soldiers at Nashville than in any other battle during the Civil War.

Some people assume that the painting depicts the final assault on Compton’s Hill, later re-named Shy’s Hill, on December 16th, 1864. It does not. The painting depicts the 5th and 9th Minnesota Regiments of Hubbard’s Brigade, A. J. Smith’s Division, attacking through the muddy cornfield to the east of the hill. Lucius Hubbard would later become Minnesota’s governor. In the charge, Hubbard was shot in the neck and had two horses shot.

It is truly a magnificent painting. There are few paintings in history that rival the desperation, courage, and outright drama of an infantry charge than this one. John Banks, podcaster, writer, and a director of the Battle of Nashville Trust calls it “mesmerizing”. But this was not the only historical military work painted by Pyle. His previous work, “The Battle of Bunker Hill” finished in 1897 as well as his other American Revolutionary War paintings are excellent examples of martial tension. The atmospherics in each pull the viewer into the action. You can very clearly see the carryover of the atmospheric drama from the Bunker Hill painting into the Battle of Nashville painting.

But was Pyle’s Nashville work historically accurate? Historical reality and artistic license are always at play in reproducing history and at times, at odds with each other. While military artists set out to portray a real event, the portrayal usually yields to the level of artistic license the artist ultimately elects to use to evoke an emotional response from the viewer and to commemorate the event in heroic fashion. Its ultimate authenticity is underpinned by how much research has been undertaken to get the weather, uniforms, and events of the battle right. Sometimes the artist doesn’t fully succeed.

A clear example is the Battle of the Little Big Horn, initially named Custer’s Last Stand, and more recently referred to as the Battle of the Greasy Grass, the Native American name for the battle. Many famous artists attempted to memorialize the battle. Most captured the drama but failed in other parts. In Frederick Remington’s painting “Last Stand” (1891), painted 15 years after the battle, the view in the painting is dramatic and evokes desperation and resignation of the soldiers’ to their combined fate, but the historical authenticity is clearly wrong. Custer is placed at the top of a rocky pinnacle resembling a cairn with his soldiers seated around him in greatcoats signifying cold weather. Sabers, which had been left behind and not at the battle, are stuck into the ground in front of the troopers reflecting to the viewer that it will be a final desperate hand to hand struggle. In June of 1876, the weather was very dry, very hot, and most troopers wore only their blouse, some even wearing straw hats purchased from the sutler on the steamer The Far West which had accompanied General Terry’s combined Custer/Gibbon force to the Rosebud, then to the Yellowstone River. In this depiction, the weather and uniforms are wrong.

In Edward Paxton’s painting of the battle, it is more accurate, but the regimental standard is wrong, the yellow cavalry flag which was to replace the blue standard having not been adopted for cavalry units until after the battle; not to mention that the regimental color was not at Last Stand Hill, the flag having been stowed with the reserve ammunition pack train following the regiment. The swirl of battle is desperate but not how it unfolded.

But The ultimate flawed painting, and a very political one at that, rests with the painting by Cassilly Adams’ “Custer’s Last Fight” (1884) commissioned by Anheuser-Busch as a poster and later prepared by Otto Becker as a lithograph advertisement (1889) heavily revised from the original, which probably hung over most of the bars across the United States. The battle space is fairly accurate and some of the intensity of the actual fighting. The dismemberment and scalping images are gruesome and terrifying. But what makes this painting politically incorrect, to say the least, is the disbelief at the time in the United States that Custer and his beloved 7th Cavalry could have been defeated by “savages”. An inspection of the central foreground introduces the viewer to a buckskin attired man with a rifle who is wearing a western hat. He is not facing the viewer…he is facing the battle with his rifle. Why is he there? Why is he with the Lakota, Cheyenne, and Arapaho and not being attacked? This figure represents the rumor that the only way Native Americans could have defeated Custer was through the strategy and tactics of a renegade white officer, presumably an ex-confederate. The white man is there, directing the attack. That is why Custer was defeated. Notice the partially nude “Michaelangelo bodies” of two dead troopers in the right foreground and the Zulu like shields of some of the warriors!

This is but one example in art. There are many. The paintings of native peoples after discovery by Europeans always elicit the question of why do they look like they just dropped off of the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel? The answer is simple…their “Michaelangeloesque” musculature was painted because no one really knew what indigenous people looked like.

With these issues in mind, let’s examine Pyle’s Nashville painting. Does the painting meet the four criteria listed below?

- Does it actually portray the event it seeks to reproduce?

- Does it realistically portray the battle space, topography and weather conditions?

- Does it accurately depict the combatants?

- And finally, does it accurately portray the battle without exaggerated artistic license?

- Portrayal of the Event. The answer is YES. Pyle’s painting seeks to represent the charge of the Minnesota regiments of Col. Lucius Hubbard’s II Brigade in the late afternoon of December 16th, 1864. John Banks’ Blog of December 20th, 2020 titled “Where are Howard Pyle’s “lost’ Nashville battlefield photos”? is an excellent post which includes present day photos of the Harding Place Road near the intersection of the Granny White Pike at the location where Pyle must have determined the charge occurred across the muddy cornfields to the north of Harding Road and east of Shy’s crest. Pyle had traveled to Nashville and took multiple photos from which he painted his epic oil and did research before painting it. He met with and consulted veterans of the battle, but his painting only represents two regiments involved in the assault out of Hubbard’s Brigade, the 5th and 9th Minnesota. The 7th Minnesota and the 10th Minnesota were not included, understandably, because the 7th was to the east of Pyle’s portrayal in Marshall’s III Brigade, which angered Capt. Thomas G. Carter of the 7th for not including his unit. The 10th Minnesota is not portrayed because it was well above Hubbard’s brigade in McMillen’s I Brigade tasked with assaulting Shy’s Hill and its location would be past the battle smoke portrayed.

- Realistic Portrayal of the Battle Space, Topography and Weather Conditions. The answer is MOSTLY YES. Shy’s Hill is accurate in its location, size and eastern slope descending to the Granny White Pike. But the foreground slope may be another story. The assault is through a muddy cornfield. There is evidence of a past ice storm among the corn stalks. It appears it is late afternoon with the sun setting in a cloudy atmosphere, all of which would be accurate. However, the foreground slope appears to be exaggerated in steepness. The charge is also exaggerated to the east. In other words, if you draw a line of the direction of the charge, the men are moving from the right to the left, in other words almost due east and away from Shy’s Hill exposing them to enfiladed fire. The earthworks or stone wall on the slope are well back. Shrouded by smoke, McMillen’s Brigade is supposedly attacking straight ahead through the smoke and up Shy’s Hill at a right angle to Hubbard. But who are the Confederates depicted in the left corner fighting at almost a 90 degree angle? They certainly aren’t pickets as they would not have attempted to contest such an overwhelming charge. In fact, first person reports from Marshall’s III Brigade state that the Confederate pickets were surprised by Marshall’s charge, as they were watching the assault to their left up Shy’s Hill and rose up en masse in panic and headed for the stone wall. And it certainly does not depict the stonewall on the Granny White as the wall is placed further back. It must represent the angle where Loring’s Division tied into Walthall’s Division. But again, the representation is more like The Angle on Cemetery Ridge at Gettysburg than at Nashville. This is where Capt. Carter may be correct. Carter stated that the topography depicted was wrong. With the background seeming to be correct, he must be referring to the foreground. From an eye test computation, it would appear that the slope is at angle from 15 to 20 degrees. A theoretical argument could be made that when Harding Road was developed, the contours were flattened but it is very doubtful that that much material would have been moved to make the road and the corresponding level home lots as it appears today. In this writer’s opinion, the direction of the attack is filled with artistic license and drama as will be discussed in Number 4.

- Does the Painting Accurately Depict the Combatants? The answer is GENERALLY YES. The Federal troops appear appropriately attired for December 1864 with appropriate weapons. Great coats and bedrolls would have been piled up before forming for the charge. There are two regimental standards and two national colors, all in tatters with the regimental and the national close together as expected. In Hubbard’s report, Hubbard mentions that several color bearers were shot down in the charge so it appears he wanted to include the danger and bravery of the color guard. The mud on many of the soldiers evidence how difficult the charge would have been through the cornfield after the ice storms, and the rains, earlier that day.

In turning to the depiction of the graycoats, what few Confederates that are depicted, the gray color of their uniforms, the slouch hats, and their heavy beards would appear to be accurate. Their grizzled faces show they are veterans attempting to make a stand. Notice few, if any at all, of the Federal troops have beards; almost to a man they are clean shaven with only a couple sporting mustaches. But the real question of accuracy in the painting is: who are the mounted men on Shy’s Hill? And why are two of them on white horses? They appear to be within cannon range and sniper fire. The mounted men appear to represent officers, not artillery. Is it Lt. General John Bell Hood and his command staff? This depiction is artistic license as more fully explained in Number 4.

- Does the Painting Portray the Battle Without Exaggerated Artistic License. The answer is NO. Pyle could not have painted the entire assault on Shy’s Hill. The painting, as he correctly stated, would have been too big. In addition, he could not have had the drama that he so wonderfully included if he had painted from behind the assault which would have had MacArthur’s whole division. Instead, he created the drama and intensity of the attack heading from the right to the left almost as an overwhelming, unstoppable juggernaut of determined men, the same as in his Bunker Hill The inclined angle of the foreground only accentuates the charge. Look at the slope of Shy’s Hill and compare it with the line of attack. The angles are the same. The line of the slope supports the angle of the charge sweeping the viewer along with the troops. We are going in with them. We cannot stop. Even the soldier with a bandaged head wound from the previous day is not going to be left behind. Note in the Bunker Hill painting (see above), Pyle included a hatless grenadier in the foreground with a bandaged head wound, another image, and symbolism, adopted into the Battle of Nashville painting. We are all on a dead run downhill. Battle has already been joined to the right of the charge as signified by the dense smoke of hiding McMillen’s brigade. Pyle cannot include that part of the battle but lets us know that there is intense fighting at the hill. The roiling smoke speaks to other battle but doesn’t detract from Hubbard’s charge; in fact it further dramatizes it, the same as his Bunker Hill painting.

Capt. Carter is right. Pyle could not have included Marshall’s Brigade the way he sought to portray the battle. But, There is a drawback to Pyle’s artistic use of angles and lines. Hubbard’s Brigade driving almost due east would have slammed into the right flank of Marshall’s III Brigade. It almost looks as if he has. Moving the charge along, Pyle would have to show the antagonists, not Marshall, so we have Confederate troops in a deep swale that probably wasn’t there and at an angle that is extremely pronounced. There was an angle in the line at the nexus between Walthall and Loring, undoubtedly, but was it that extreme?

And finally, it appears to this writer that the rider on the white horse on Shy’s Hill is General Hood. The other horsemen would be his command staff and probably officers from Bate’s Division. I have not seen a picture nor a description of Gen. Hood on a white horse. Most paintings of Hood depict him on a Bay or Chestnut Horse, both at Gettysburg and at Nashville. But, in the movie “Gettysburg”, Hood is mounted on a white horse. Whether that is Hollywood or not, I don’t know. Most general officers had more than one horse, but I think that the white horse in this painting is utilized to represent a warrior leader. White horses have always had that symbolism. With a white horse it is easy to spot the leader, in this case, General Hood surveying the attack that would break his line and result in the rout of his army. Hood is “Danger Close” so it is doubtful he would have been in that position. Did Pyle purposely place Hood there in the painting so he could witness the destruction of his army by Hubbard’s Minnesota troops? In actuality, Hood was at the Lea home when advised of the break in the line so there is artistic license at play in putting him on the field of battle.

Conclusion. While it appears that I may have sought to poke holes in the painting, it was not my intent. After critically reviewing it, I walk away with even greater admiration for it and Pyle’s skill. He was ahead of his time in realism. He had researched his subject well, and though Col. Hubbard was included in the painting, he was not glamorized, only barely noted, nor was he the central figure as you would expect. Instead it was the common Minnesota farm boy that Pyle sought to exalt and in that mission, he succeeded. The intensity of an infantry charge I don’t think has ever been exceeded by any other painter, and the artistic license he took to frame the charge is in lasting tribute to those Minnesota farm boys that day.

Sunday, November 16, 2014

MINNESOTA MONUMENT DEDICATED ON SHY’S HILL

On Sunday, November 16, 2014, in a drizzling rain reminiscent of December 16, 1864, a granite monument was dedicated on the northeastern slope of Shy’s Hill in memory of the 97 Minnesota troops who died in a bloody but successful uphill charge there 150 years ago. It was the first such monument placed on any part of the Battle of Nashville battlefield to specifically commemorate Union troops.

On Sunday, November 16, 2014, in a drizzling rain reminiscent of December 16, 1864, a granite monument was dedicated on the northeastern slope of Shy’s Hill in memory of the 97 Minnesota troops who died in a bloody but successful uphill charge there 150 years ago. It was the first such monument placed on any part of the Battle of Nashville battlefield to specifically commemorate Union troops.

Click HERE to view the Minnesota Historical Society’s video describing the Minnesota monument, the dedication ceremony and the important role played by Minnesota troops in the battle at Shy’s Hill. The unveiling and dedication of the monument was one of the many events which make up the commemoration of the Battle of Nashville Sesquicentennial. It was jointly hosted by the Minnesota Civil War Commemoration Task Force and The Battle of Nashville Preservation Society (BONPS). The monument had been placed by crane on November 3, 2014, with the help of BONPS board member Parke Brown and others.

A contingent of Minnesotans traveled the 900 miles to Nashville to participate in the dedication ceremony. For a closer look at the importance of the monument to the people of Minnesota, read “Eloquence At The Battle of Nashville,” an article published on November 8, 2014, in the Minneapolis Star Tribune by columnist Curt Brown, describing the long bus journey southward, its meaning to the State of Minnesota, and the story behind the moving inscription on the face of the new monument (Note: The article inadvertently reports the number of Minnesota casualties at 87 rather than the actual 97).

The dedication event and the monument itself highlighted the Battle of Nashville and the pivotal role played by the four Minnesota regiments on December 16, 1864. On that day, under orders given in the late afternoon of the rainy day by Brig. Gen. John McArthur, the four regiments made the decisive charge up Shy’s Hill, collapsing the Confederate line and becoming the pivotal moment in what is considered the last major battle of the Civil War.

Under the rain-soaked tents during the dedication, numerous speakers lent perspective to the Shy’s Hill fighting and the meaning of the monument, which marks the bloodiest single day of the war for Minnesota troops.

Above: Minnesotan Ken Flies addresses attendees

Above: Minnesotan Ken Flies addresses attendees

Among them was Ken Flies, whose great-great-grandfather fought in the Tenth Minnesota Infantry and died in Tennessee. He is chairman of the Soldier Recognition Committee of the Minnesota Civil War Commemoration Task Force which initiated the Monument concept. The Committee worked jointly with the Battle of Nashville Preservation Society along with the Land Trust for Tennessee, organizations which have been instrumental in saving many of the major sites of the Nashville battlefield.

During his remarks, Ken read aloud the inscription on the monument, which was written by a Minnesota private, John Milton Benthall, in a document which Ken discovered in his meticulous research of the battle:

“… comrades who have grown as dear to us as brothers lie dotting the steep hillside, their battles ended, their warfare over. Never more will they press with us shoulder to shoulder as the bristling steel points sweep resistlessly on, never more in our hours of glee will their voices join in the merry jest or fill the air with laughter — they are gone. And the everlasting mountains in the shadow of which they lie shall be their eternal monument; year after year the forest trees will shed their crowns of glory over them, and day by day the winds, as they sigh through the Brentwood Hills, will chant a low, sad requiem to their memory.”

The story of how Ken discovered the author of the report from which these words were taken is a story of tenacious historical investigation and persistence. He tells the story in the article below, and along with it, has provided BONPS with a copy of the actual report by Private Benthall:

Jacob Milton Benthall Biography

The Tenth Minnesota News

Other speakers included a welcome by John Allyn, president of BONPS, and Ann Toplovich, executive director of the Tennessee Historical Society.

The Minnesota keynote address was delivered by the Hon. Dean Urdahl, Minnesota State Representative, followed by the Nashville keynote address by Jim Kay, former president of BONPS and noted Battle of Nashville historian. During the ceremony, the names of each of the 97 fallen Minnesotans was read aloud.

After the Minnesota delegation presented Tennesseans with a beautifully-framed print of the famous Howard Pyle painting of the battle at Shy’s Hill, the unveiling occurred on the hillside by Rep. Urdahl and Jim Kay, and the laying of a memorial wreath by the Minnesota Task Force representatives.

The new monument complements the Memorial Flag Plaza and park at the summit of the hill, which is maintained by BONPS. The placement was on a slight plateau area on the northeastern slope of Shy’s Hill, the area over which many of the Minnesota troops attacked dug-in Confederate troops in the late afternoon of December 16, 1864. For a more complete summary of the battle at Shy’s Hill, click here.

Shy’s Hill Trail Rebuilt for Sesquicentennial

In February, 2014, BONT Board member Parke Brown and his professional landscaping crew from The Parke Company, Inc. (http://www.theparkecompany.com/) rebuilt the winding trail up the East slope and gave the summit a facelift with weedeaters and chain saws.

The result: Shy’s Hill and its topside memorial plaza look like a well-manicured state park, just in time for the commemoration of the 150th anniversary of the battle on the hill on December 16, 1864.

“It’s a good time to experience the uphill walk and contemplate the sacrifices made during battle,” Parke said. His crew spent 100 man hours in February, 2014, installing the 150 8-foot beams which are laid out end-to-end to line the winding three-foot-wide trail. Each beam was drilled and then anchored into the hillside with three 24-inch iron rebar rods. The trail surface was then filled with 12 cubic yard of hardwood mulch.

In all, the project resulted in the installation of 1,200 linear feet of 4×4 beams (purchased and delivered up the hill by Board member Sidney McAlister, Parke noted) and 420 pieces of rebar.

Shy’s Hill as Photographed in the 1880s and 1890s

December 2011: Sesquicentennial Commemoration Begins

THE BATTLE OF NASHVILLE DECEMBER 15 – 16, 1864

In the Sesquicentennial year, The Battle of Nashville Preservation Society, Inc. honored the memories of soldiers of the Union and Confederacy who fought and sacrificed in this profound historical event by placing memorial wreaths on two of its battlefield preservation sites which symbolize the deadly conflict on each of the two days of the battle — for December 15, 1864, Redoubt No. 1, and for December 16, 1864, Shy’s Hill. Below is President Philip Duer’s commentary on the event:

A Message from Philip Duer, President of BONPS 2011 – 12

December 16th, 2011

As I ascended Shy’s hill this morning to place our memorial wreath below the flags flying at the summit, I was struck by the thought that this day was the same 147 years ago — a chilling rain, fog, and a coldness that made the day heavy and miserable.

But today was not the same, it was different; I could ascend the hill with no thoughts of harm save for slipping on some wet leaves, and I was comfortable in my waterproof jacket and boots. I had no fear of being shot, wounded or maimed. I calmly walked up the hill, not rushing in desperation to reach the top. No one was trying to kill me nor I them. I was climbing the hill in peace.

I had no grief nor emotional trauma to deal with from the horror of Franklin. I had no reason to keep my head down. I had no hunger pangs, thoughts of home, nor whether I could survive not only the cold but other men trying to take my life. I didn’t have to press my body against the earthworks. I could stand in safety and view the panorama from Shy’s Hill in contemplation as to what it must have been like. I could see the hills where Union artillery fired hundreds of shells. I could see the lines of infantry and cavalry forming up for the assault. I could try and picture the scene as men fell and died on both sides. But in reality, I could not know what it was like, I could not perceive the horror of watching friends die, of the fear and panic, of waiting for the dreaded inevitable conclusion or of the jubilation of victory.

No, today is not the same save in one respect and that has been that every year since the battle people have remembered those who fought and gave their lives for what they believed in as they saw it, which in the end made us all Americans. It is inconceivable today that the mistakes made to cause such a war will ever happen again. It is for that fact that we remember their sacrifices. I can leave that hill in peace as I found it.

Philip Duer

BONPS President

December 16, 2012

A MOVING TRIBUTE TO THOSE WHO FOUGHT

In an extremely rare occurrence, the 148th anniversary of the Battle of Nashville fell on a weekend this year. On December 16, 2012, BONPS invited the public and descendants of the Battle of Nashville to meet at the summit of Shy’s Hill for a moving commemoration of the December 15 -16, 1864 Battle that triggered the end of the American Civil War.

In an extremely rare occurrence, the 148th anniversary of the Battle of Nashville fell on a weekend this year. On December 16, 2012, BONPS invited the public and descendants of the Battle of Nashville to meet at the summit of Shy’s Hill for a moving commemoration of the December 15 -16, 1864 Battle that triggered the end of the American Civil War.

A crowd of more than 100 climbed the trail to the top of Shy’s Hill on Sunday, December 16, 2012, to participate in the memorial event remembering the men who fought and those that fell in the Battle of Nashville.

The program included opening comments by BONPS President Philip Duer and a fact-filled presentation by noted historian Ross Massey as to the significance of the battle and of the Hill’s climactic role. Union and Confederate re-enactors attended the placement of the memorial wreath, accompanied by the martial drum of Paul Smith prior to placement and the violin of local musician Linda Gale Rose in conclusion.

Those placing the wreath included Ken Fieth of Nashville, whose ancestor was Brig. Gen. Thomas Benton Smith of the 20th Tennessee Infantry, who was captured at Shy’s Hill. The Shy’s Hill trail head begins at the street named in honor of the general — Benton Smith Road. Placing the wreath for the Union were BONPS board member Gary Burke of Nashville, whose ancestor fought with the 17th USCT, and David Clark, two of whose ancestors fought with the 35th Irish Indiana Inf. (Irish) Regt.

BONPS sought out descendants of the soldiers of both sides who fought in the Battle of Nashville. Many families, representing ancestors from the Union and the Confederacy, attended the event and participated in placing the memorial wreath. Their attendance was recorded in a group photograph (ancestor’s name, regiment, and unit organization will be published on the BONPS website and recorded as a historical Sesquicentennial event).

Histories, documents and photos sent to BONPS by the descendants and their families have been placed on a special Descendants page on the website. BONPS continues to invite descendants of the Battle participants to send their information for posting on the website.

(Click to enlarge) Descendants of the Battle of Nashville soldiers stand on the summit of Shy’s Hill with the Memorial wreath on December 16, 2012

Click on the individual images below to read the photo captions.

- Napoleon awaits the ceremony on the Shy's Hill summit

- Philip Duer and Ellen McClanahan, left, check in visitors to the Shy's Hill Memorial

- Drummer Paul Smith and John Mansfield

Drummer Paul Smith and John Mansfield

- Ross Massey speaks at the summit with Elizabeth Coker in the background

- Philip Duer looks on as Fred Crown, with grandson, tells of his ancestor

- Replica battle flag

- Memorial flags at half-staff in honor of the fallen

- BONPS board member Gary Burke tells of his ancestor who fought with the 17th USCT

- Incoming BONPS president John Allyn with sons Jack (left) and George, descendants of a Confederate chaplain

- BONPS president Philip Duer

- David Clark and Gary Burke standing with descendants

- Nashvillian Ken Fieth laid the wreath in honor of his ancestor, Brig. Gen. Thomas Benton Smith who fought on Shy's Hill

- Memorial wreath placed by descendants

Below are some of the features related to the Memorial event:

• Philip Duer: Reflections on Shy’s Hill

• Why the Minnesota Flag on the Shy’s Hill Summit?

• War letters from home: A foot soldier tells about Nashville

• Interview with Shy’s Hill Artist Col. Howard Massey

• BONT Board Attacks the Hill

Why Fly the Minnesota Flag Atop Shy’s Hill?

“People wonder why we fly the Minnesota State flag at the summit of Shy’s Hill. For those who are knowledgeable about the battle here, it was the Minnesota regiments who assaulted the hill and charged across muddy cornfields below it to break the Confederate line on the second day, Dec. 16th, 1864. Howard Pyles’ painting (at the Shy’s Hill kiosk) portrays that dramatic attack. Minnesota suffered the most casualties at Nashville than in any other battle. It is with thanks to Vern Ege who has brought this article to our attention of a man devoted to finding the graves and stories of CW soldiers from Minnesota. His inspiration — stories of 2 soldiers from Minnesota who died at Nashville! While not the bloodbath of many battles, the story of Nashville continues to be of interest. One only has to read the late David Logsdon’s “Eyewitness to Nashville” to feel the growing tension, excitement, and despair as both armies faced off for 2 brutally cold weeks before the battle.

Vern’s ancestor’s story is provided below as we document those who fought here. http://www.startribune.com/local/178468071.html

Philip Duer, Pres. BONPS

Knud Otterson. Descendant: Jane Otterson Miller (& husband Vernon Ege). Private Knud Otterson was with Co. A, 5th Minnesota Infantry in which he volunteered early in the war in 1862 and despite two war wounds over the ensuing three years, finished his tour of duty in Alabama in 1865. Jane Miller is his great granddaughter and she and husband Vernon Ege have written a heavily-researched 27-page booklet telling Knud’s fascinating story as a Minnesota infantryman. That story includes his harrowing ordeal in Nashville, where he was with the 5th Minnesota when it charged across open fields and up the slope of Shy’s Hill on Dec. 16, 1864. This is the charge that is depicted in the famous Howard Pyle painting posted on the Home page of this website. In the charge across open ground, Knud was wounded in the left hip by a shell fragment and spent time in Cumberland Hospital in Nashville before getting additional care and ultimately being reassigned to Alabama, where he was on duty at war’s end. Below is a PDF link with the initial draft of the booklet, not yet in final form. But Jane and Vernon has granted permission to BONPS to included it on this page for the Shy’s Hill Memorial.

The Civil War Journey of Knud Otterson, 5th Minnesota Infantry

A Civil War Letters To His Family: Nashville and Beyond

“Attached are multiple letters home from a German farm boy, Friedrich Giessler, writing home to his parents and siblings in Ohio starting in early October 1864 through January 8th, 1865. He was drafted September 21st, 1864 and served in Co. C, 41st Ohio Infantry. The translation done years ago seeks to include Pvt. Giessler’s spelling as for example “Neschwill, Tenesi” or for Hood “Hutt”, for dollars “Talers.” The letters are very interesting as they tell his story as a railroad guard on the trains going south before coming to his unit after Atlanta and Hood has moved north. He was at Franklin (in reserve) and was placed in the hospital later at Nashville because of illness by his sergeant at Hume School hospital. He witnessed the Confederate prisoners after the Battle of Nashville in downtown Nashville. It is with thanks that we have these letters from his descendant, Chip Giessler, a Methodist minister. Some things don’t change in war. Note he asks for money all the time from his family. These letters provide a good insight into the common soldier’s perspective, not grand military maneuvers but the day to day worries and aspirations of the ordinary foot soldier.” The first page shows Giessler and his friend Phillip Gehres. Philip Duer, BONPS president.

War letters of Friedrich Giessler, 41st Ohio Infantry

Reflections of former BONT president Philip Duer as he placed the memorial wreath at Shy’s Hill in 2011:

December 16th, 2011

As I ascended Shy’s hill this morning to place our memorial wreath below the flags flying at the summit, I was struck by the thought that this day was the same 147 years ago…. a chilling rain, fog, and a coldness that made the day heavy and miserable.

But today was not the same, it was different; I could ascend the hill with no thoughts of harm save for slipping on some wet leaves, and I was comfortable in my waterproof jacket and boots. I had no fear of being shot, wounded or maimed. I calmly walked up the hill, not rushing in desperation to reach the top. No one was trying to kill me nor I them. I was climbing the hill in peace.

I had no grief nor emotional trauma to deal with from the horror of Franklin. I had no reason to keep my head down. I had no hunger pangs, thoughts of home, nor whether I could survive not only the cold but other men trying to take my life. I didn’t have to press my body against the earthworks.

I could stand in safety and view the panorama from Shy’s Hill in contemplation as to what it must have been like. I could see the hills where Union artillery fired hundreds of shells. I could see the lines of infantry and cavalry forming up for the assault. I could try and picture the scene as men fell and died on both sides.

But in reality, I could not know what it was like, I could not perceive the horror of watching friends die, of the fear and panic, of waiting for the dreaded inevitable conclusion or of the jubilation of victory.

No, today is not the same — save in one respect, and that has been that every year since the battle people have remembered those who fought and gave their lives for what they believed in as they saw it, which in the end made us all Americans. It is inconceivable today that the mistakes made to cause such a war will ever happen again. It is for that fact that we remember their sacrifices.

I can leave that hill in peace as I found it.

Philip Duer

Former President BONPS/BONT

Shy’s Hill Art Work: An Interview With Col. Howard Massey