Selected articles featuring the men who fought in the Battle of Nashville

___________________________________________

October, 2024

THE DIARY OF A PRIVATE IN FINLEY’S FLORIDA INFANTRY GIVES A GLIMPSE OF HIS EXPERIENCES IN THE BATTLES OF FRANKLIN, MURFREESBORO, AND NASHVILLE

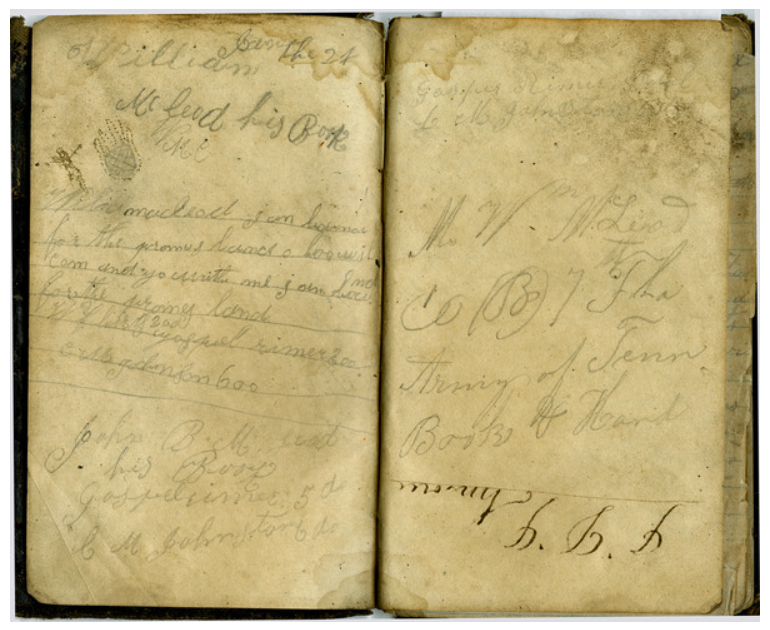

A first-person account of a Confederate soldier in the Battle of Nashville is part of a handwritten diary by a member of the Seventh Florida Volunteers which has been made available to the website by Bobby Whitson, President of the battle of Nashville trust.

The diary was written by William McLeod, a private in Co. B of the Seventh Florida. The regiment was part of the all-Florida Finley’s Brigade, which at the time of the Battle of Nashville was commanded by Brig. Gen. Robert Bullock. Finley’s Brigade was part of Bate’s Division which was tasked with defending the summit of Shy’s Hill. It was placed in the middle or “point” of the Division’s line at the top of the Hill, facing northwest, with Tyler’s brigade on their left, and Jackson’s on their right.

Diary of William McLeod, 7th Florida Volunteers. Click photo of diary to open to its pages and transcription. See text below for guidance.

McLeod’s diary is most relevant to the Battle of Nashville on Pages 36 – 42. Finley’s Brigade was in Cheatham’s Corps at the Battle of Franklin, but when the rest of Hood’s Army of Tennessee headed north toward Nashville after Franklin, Bate’s Division was ordered to Murfreesboro, along with two divisions of Gen. Nathan Bedford Forest’s cavalry, to destroy Union railroad facilities. In Murfreesboro, in the vicinity of Fortress Rosecrans, Bate’s Division was unsuccessfully involved in the Battle of the Cedars, in early December, forcing them back to the Confederate line just prior to the Battle of Nashville.

To read the diary, click on the photo of McLeod’s title pages to open the website containing the journal. When the website is open, the pages are arranged as thumbnails. Click on any thumbnail to open and read the original writing, and at each page, scroll down to see the typewritten transcription. Examples of the entries include McLeod’s experience in the Battle of Franklin at page 36, the sleet and snowstorm that hit Nashville just prior to the battle on page 39, and the battle at Shy’s Hill on page 41.

Recollections Of A Confederate Major

Travellers Rest, headquarters of Gen. John Bell Hood

Maj. Joseph B. Cummings was assigned to the staff of Gen. John Bell Hood. After the war, he wrote a colorful first-person account of his involvement in the battle and Hood’s staff, from the end of the Battle of Franklin to his final retreat back to Franklin. His paper, ‘War Recollections,” is in the Southern Historical Collection at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. In this excerpt, he gives a personal glimpse of his days at Traveller’s Rest (John Overton’s home) where Hood set up his Nashville HQ, his faithful devotion to a barrel of Robinson (Robertson?) County whiskey, his “damn fool” exploits on a white horse during the fighting, a surprising meeting with a Union soldier, and his night time escape through open fields after the rout of the Confederate army on December 16.

Recollections of the Battle of Nashville by Maj. Joseph Cummings

_____________________________________________________________

NEW BOOK ON WAR IN TENNESSEE NOW TRANSLATED FROM GERMAN TO ENGLISH

1st Lt. Fred. W. Fout was a German immigrant who fought in the battles of Franklin and Nashville as a First Lieutenant of the 15th Independent Indiana Artillery Battery. He later wrote a Civil War history based in large part on his own experiences throughout the war, but the volume containing his history and recollections of the campaign under Generals Schofield and Thomas in Tennessee was only published in German in 1902, entitled Die Schwersten Tage des Bürgerkriegs, 1864 und 1865 (The Darkest Days of the Civil War, 1864 and 1865). Philip Graupner has now translated this volume and it is available from lulu.com under the title.

According to Mr. Graupner, Fout was born in October, 1839, and immigrated alone at about age 15 in 1855 to live with his uncle in New Palestine, Indiana. He went to school there, and also learned the carpentry trade. He attended the Franklin Academy near Indianapolis to further his education and ultimately volunteered at the beginning of the war with some friends in a 3-month unit. After that ended he worked for a while, but then re-enlisted in an artillery battery and eventually becoming a member of the 15th Independent Indiana Light Artillery battery in which he fought for the rest of the war. He did not become an American citizen until after the war. He wrote two volumes on the Civil War, based in large part on his experiences. Vol. 1 has been published in English.

___________________________________________

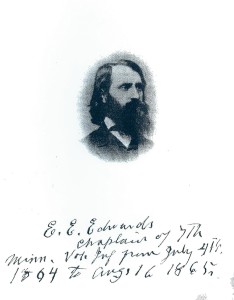

The Words and Drawings of E.E. Edwards

Minnesota Chaplain’s Diary Describes the Battle of Nashville

Elijah Evan Edwards was a 33-year-old man of letters when he arrived in Nashville as Chaplain of the 7th Minnesota Volunteer Infantry.

He had already served as a professor of ancient languages and president of a college, as well as completing his seminary work, by that time.

His descriptions of the days leading up to the Battle of Nashville and of the fighting itself are matched only by his contemporaneous drawings of battlefield vignettes and maps. His keen eye brings us exquisitely written and detailed descriptions 150 years later of the details of the Bradford house, conversations with Mary Bradford, the sounds of artillery shells, the sights in the trenches littered with their casualties, conversations with Confederate and Union soldiers, and scenes from the attacks on the redoubts and Shy’s Hill.

The existence of this historical treasure in easily-readable form would not have been possible without the painstaking transcriptions from the Chaplain’s handwritten diary by Ruth P. and Roy L. Cunningham, for which we are truly grateful.

Click on the PDF link below for this interesting first-person account of the battle, the environment, and the people he observed during Nashville campaign.

Civil War Diary of Chaplain E.E. Edwards, 7th Minnesota

_____________________________________________________________

Union Soldier’s Letter Describing Nashville and the Battle

The link below contains a transcription of a letter written by Union soldier Charles Grundy to a friend, “Henry,” on December 19, 1864, three days after the Battle of Nashville. Grundy, who was assigned to Sherman’s Army, had been in Nashville since December 3 and in his letter, describes his eyewitness account and observations of the city of Nashville during this time, as well as the battle on the second day, December 16, 1864. The original letter is in the collection of Jim Kay, former President of BONPS.

Charles Grundy letter 12-19-64

_____________________________________________________________

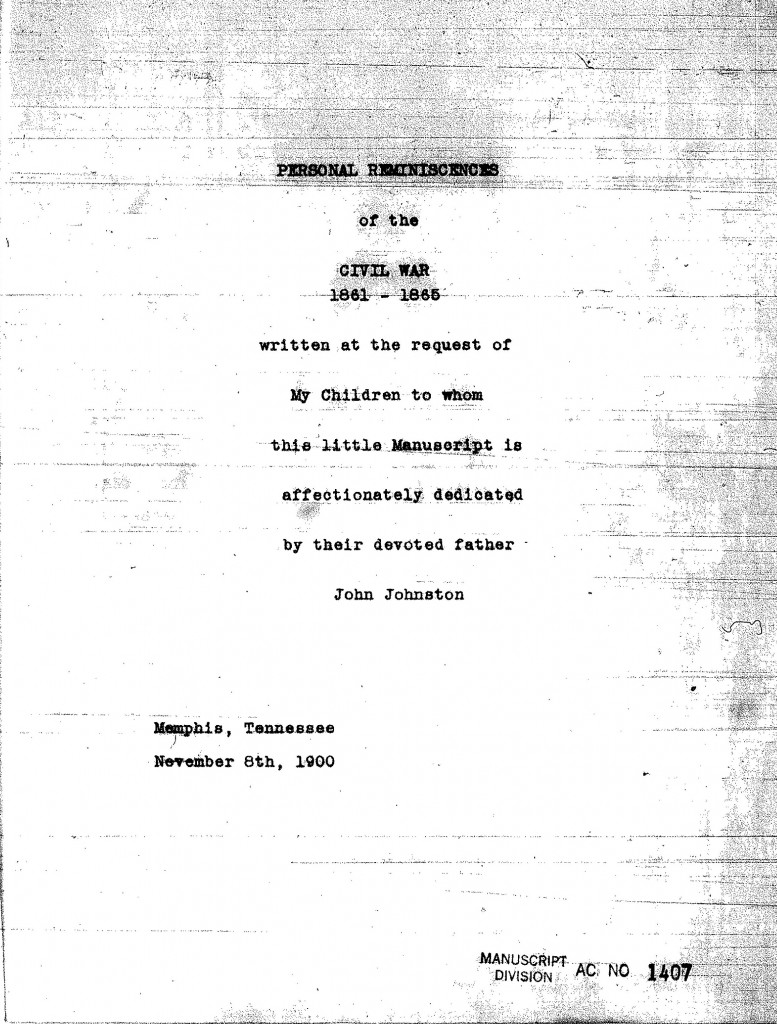

PRIVATE JOHN JOHNSTON’S RECOLLECTION OF THE BATTLE OF NASHVILLE

Confederate private John Johnston of the Fourteenth Tennessee Cavalry was present at both Franklin and Nashville in December, 1864. After the war, Johnston returned to Memphis where he worked as an attorney. In 1900, more than 35 years after the war, he wrote a lengthy memoir entitled “Personal Reminiscences of the Civil War.” The typed manuscript is maintained in the Tennessee State Library and Archives.

Among Private Johnston’s more interesting recollections about Nashville was his involvement in what is now known as the “Battle of the Barricade” on Granny White Pike on December 16, 1864. In addition to writing about this skirmish in his memoir, he later returned to Nashville in 1904 to visit the site by horse and buggy and to sketch the only known map of the battlefield. As a result of Johnston’s documentation, Jim Kay, a recognized Nashville battle expert and former president of BONPS, and Nashvillian Fowler Low were able to determine the location of the barricade battle that began just north of Richland Country Club.

Jim Kay has had the Franklin and Nashville portions of “Reminiscences” retyped into more readable form, and they are presented here by BONPS as one of the more interesting journal descriptions of the Battle of Nashville through the eyes of a Confederate private. The Battle of the Barricade is now marked by a historical marker on Granny White Pike at Club Drive. It was dedicated by BONPS in 2008.

Above is the original cover page for Private Johnston’s memoirs. Click on the link below to read the 17-page segment in which he gives his eye witness account of the battles of Franklin and Nashville:

John Johnston’s “Personal Reminiscences of the Civil War”

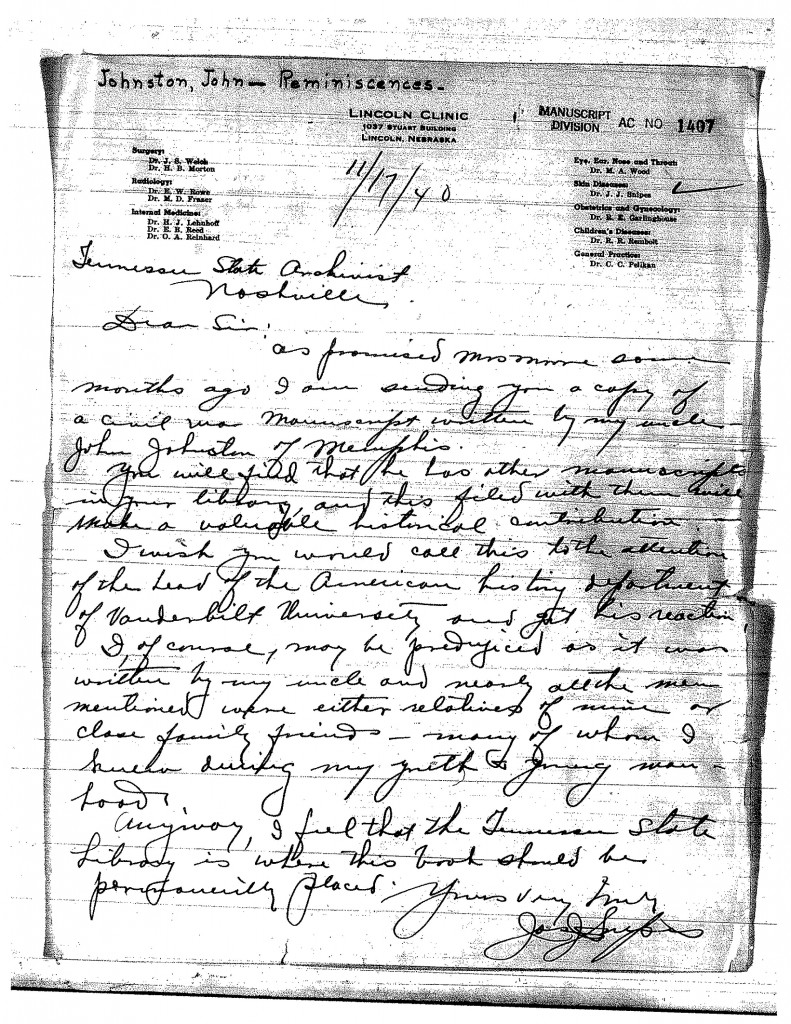

The link below contains portions of the original manuscript and the 1940 letter by which Private Johnson’s memoir was first introduced publically by his nephew.

Johnston Manuscript Cover and Letter

______________________________________________

PERSONAL ACCOUNT FROM THE CONFEDERATE LINES

Nashvillian Henry D. Hogan, writing in the Christian Advocate newspaper published on February 10, 1922, recounted for readers his memories of the eve of the Battle of Nashville. As a Confederate soldier, he had been assigned to help guard his uncle’s farm next to the estate of Judge John Overton (now known as Travellers Rest).

Henry Hogan’s Recollections of the Battle of Nashville

____________________________________________

CONFEDERATE BATTLE OF NASHVILLE CASUALTY BURIED IN NASHVILLE NATIONAL CEMETERY

By John Allyn, member of the BONPS Board of Directors and President of the Nashville City Cemetery

The National Cemetery system was created by the Federal government following the Civil War to provide burial places for thousands of Federal soldiers who died at scattered posts and battlefields throughout the South. There was a concern that these graves would become lost or forgotten or, worse, would be vandalized by the local citizenry who still held a low view of Yankees, regardless of whether they were dead or alive. If you’re interested in learning about this subject, let me recommend This Republic of Suffering by Drew Gilpin Faust.

In the years between 1866 and 1871 approximately 303,536 Federal dead were reinterred in 74 National Cemeteries created during that period. One of the largest was the National Cemetery in Nashville, with 16,489 burials.

Burial in a National Cemetery is limited to those who served in the Armed Forces of the United States. This would expressly exclude Confederate dead. There are some exceptions. For example the National Cemetery at Shiloh includes two captured Confederates who died of their wounds in the weeks following the battle and were interred there simply because all the Union soldiers who died of their wounds were being buried there. There also have been special instances justifying Confederate burials in National Cemeteries. For example, thirty Texas Confederates killed in 1862 at the Battle of Glorieta Pass in New Mexico were reinterred at the Santa Fe National Cemetery in 1993 after their mass grave was discovered during the course of road construction near the battlefield.

And some were buried in a National Cemetery by mistake. One of these was Daniel W. Carabine, a private in Cowan’s Mississippi Battery, who died of wounds received at the Battle of Nashville.

Carabine was born in 1842 in Ireland and emigrated with his family to the United States in 1844. In 1860 he lived with his mother, sister, and two brothers in Vicksburg, Mississippi.

In May, 1862 Carabine enlisted as a private in Company G of the 1st Mississippi Light Artillery and served in the Vicksburg area until May, 1863. Confederates named their batteries rather than numbering them, and so Company G became known as Cowan’s Mississippi Battery, named after its first commander, James J. Cowan, a Vicksburg merchant.

From the time of the Vicksburg campaign through the Battle of Nashville, Cowan’s Battery was attached to W. W. Loring’s Division. Initially part of Pemberton’s Army defending Vicksburg, Loring’s Division was knocked loose from Pemberton’s Army in the wake of the Battle of Champion Hill on May 16, 1863.

Roughly half of Cowan’s Battery remained with Loring, who joined up with Joseph E. Johnston in the Jackson – Canton area. The other half went with Pemberton into the Vicksburg fortress. And some, including Carabine, did not go with either group. We know this because on June 17, 1863 Carabine and a companion were apprehended by a Confederate patrol at the home of his brother-in-law, Russell Vial, who served as a guide for Grant’s army. Carabine told his disbelieving interrogator that they were merely waiting for “an opportunity to enter Vicksburg.”

In any event, Carabine rejoined Cowan’s Battery and served with it through December, 1864. At the time of the Battle of Nashville the battery was armed with four Napoleon guns and was part of the artillery reserve for Loring’s Division, which by now was attached to Stewart’s Corps. On the afternoon of December 15 the battery was sent to cover the retreat of Deas’ and Manigault’s Brigades from the line along the east side of Hillsboro Pike. The battery set up on high ground roughly where Shy’s Hill Road dead ends overlooking the Burton Hills development. Joseph Cooper, the Tennessee Unionist commanding the brigade which assaulted the battery, described the action:

“Nothing of importance occurred until 1 p.m., when I was ordered to form on the right of General [A. J.] Smith, commanding Sixteenth Corps. I moved by the right flank until I passed General Smith’s right, and then moved briskly forward to support the dismounted cavalry [Hatch’s Division], who gallantly charged a strong position of rebels in our front [Redoubt No. 5], and captured a number of prisoners and some artillery. I continued to move forward across the Hillsborough Pike, until passing through an open field the enemy opened with artillery and musketry from a high hill in our immediate front. As soon as the rebel battery opened the men, without waiting for orders, commenced cheering and rushed forward, charging up the hill at the double quick. The lines were necessarily much broken, owing to the extreme difficulty of climbing the hill, but the men rushed forward as best they could and soon gained the top of the hill, and captured three pieces of artillery and a number of prisoners.”

Edmund T. Eggleston, a gunner in Cowan’s Battery, had a somewhat different view of the action, noting in his diary:

“Thurs [December] 15th”

“Heavy skirmishing on our left this morning. We went to the left this evening and lost our guns & horses. The infantry [Deas’ and Manigault’s Brigades] ran like cowards and the miserable wretches who were to have supported us refused to fight and ran like a herd of stampeded cattle. I blush for my countrymen and despair of the independence of the Confederacy if her reliance is placed in the Army of Tennessee to accomplish it. There are ten men from the battery missing supposed to be killed or captured. . . . All of the Co. papers and records were lost, and all of my blankets, and rations. Expect to freeze this winter.”

Tennessee Historical Quarterly, December 1958, p. 356.

Carabine, one of the ten missing men, was wounded and captured. He was taken to Hospital # 1 which was the Nashville POW hospital. On admission he was listed as a Confederate and as a member of “Mank’s Battery”, possibly a garble of “Myrick”. He died of his wounds on December 22 and was buried in the U. S. Government Burial Ground south of City Cemetery. W. C. Cornelius, the official U. S. Government undertaker, listed him as a Confederate soldier, and this was confirmed in an 1865 newspaper article.

Nonetheless, Carabine’s remains were removed in 1867 to the Nashville National Cemetery where he lies in Plot G79733:

Daniel W. Carabine’s grave marker at Nashville National Cemetery.

Roll of Honor, Volume XXII (Quartermaster General, U. S. War Department, 1869) lists all soldiers buried in the Nashville National Cemetery by state, with separate entries for U. S. Regulars and U. S. Colored Troops. Carabine is listed as a “miscellaneous” burial, a category that included named soldiers whose units could not be identified by state. Roll of Honor shows Carabine as being a member of “Monk’s Battery”.

Carabine also has a marker at Confederate Circle at Mt. Olivet Cemetery in Nashville. However, giving the nature of the burials at Confederate Circle – it is essentially a mass grave – it is virtually certain that his remains are not there.

_______________________________________________________

LOST GRAVE OF BATTLE OF NASHVILLE UNION HERO FOUND IN MICHIGAN

We recently received the following e-mail from Colonel Joe Mazurek in Michigan describing some remarkable field work in finding the grave of Captain Job Aldrich, a company commander with the 17th U.S.C.T. who was killed at Granbury’s Lunette on December 15, 1864.

Hi All,

About a year ago we communicated a bit on a Civil War soldier named Job Aldrich. He was a captain in the 17th U.S.C.T. and was killed on the first day of the Battle of Nashville near Granbury’s Lunette. His regimental commander (and brother-in-law) was Colonel William Shafter. Colonel Shafter may be a more familiar name to you as he was a recipient of the Medal of Honor for his actions early in the Civil War and later as Commander of U.S forces in Cuba during the Spanish-American War. Both Aldrich and Shafter were from the small town of Galesburg, Michigan near where I live.

I learned that Aldrich’s remains were returned home for burial and he was laid to rest in the Shafter family cemetery. Captain Aldrich was married to Colonel Shafter’s only sister, Ann Eliza Shafter. This cemetery was abandoned about a hundred years ago, remains on private land, and took some doing to even locate as it is in the middle of a thick, overgrown forest. I teamed up with the local Galesburg historian, Mr. Keith Martin, and together we have done some clean up the site. Last year we discovered a few old headstones that had long ago fallen and were buried in the earth and righted them. All in all, we located 10 gravesites, including that of Captain Aldrich’s widow. Unfortunately, as of last fall we had not located the gravesite of Captain Aldrich.

Above: The primary section of the Shafter cemetery after some extensive brush removal. Photo taken October, 2011.

I think that’s the story up through the time we last communicated and as promised I thought I would update you on things as they developed. So here goes . . .

I spent last winter following up on the family of Captain Aldrich as well as the Shafter family. He was survived by his widow, Ann Eliza Shafter Aldrich, and three sons. Captain Aldrich was born in Morris, New York on April 4, 1828. He was listed as a teacher in New Lisbon, NY on the 1850 census. Sometime after that he came to Michigan, probably by way of the Erie Canal, as did many of the early settlers to West Michigan. He married Ann in November of 1856 in Galesburg. Together they had three sons (James born in Dec 1858, Hugh born in May of 1861 and Willard born in June of 1864).

Job apparently worked as a teacher (as did Colonel Shafter prior to the Civil War and may have been how they first became acquainted), as a Justice of the Peace, Postmaster and immediately prior to his civil war service, was in the Hardware business in Galesburg.

After Captain Aldrich was killed Ann later remarried and had three additional children. She passed away in 1889 at the age of 51 and was buried in the Shafter Cemetery. The two oldest sons both made their way to the San Francisco area. James first served as a captain in the Army during the Spanish War with the 9th and 35th Infantry with duty in the Philippines before settling in California. Hugh was a prominent attorney, no doubt assisted by two of his Shafter uncles (Oscar and James McMillian Shafter), both lawyers and one of whom was a Justice of the California Supreme Court. Of course, his other uncle, Major General William Shafter was the commander of the Department of California, which doubtless helped as well. The third son, Willard, was listed on the 1880 census as working on the family farm but I was not able to locate any information on him after that. More than likely after his mother passed away in 1889 he moved on to some other location outside of Michigan.

Unfortunately…as far as I’ve been able to track there do not appear to be any direct living descendants from the Aldrich family. I researched all the other known burials at the Shafter cemetery which provided a lot of interesting local history that I won’t bore you with. In the course of all this I did learn that Captain Aldrich was a Mason which turned out to be a critical clue. Also, I was able to locate a description of Captain Aldrich’s history with the 17th USCT in Wiley Swords book Courage Under Fire, pp 126-132. This includes the circumstances of his death as well as the text of the letter Colonel Shafter wrote to his sister after the battle. It’s well worth reading if you can locate a copy.

Job Aldrich was enrolled in the Army on October 4th, 1864 as a 1st Lieutenant and Adjutant to Colonel Shafter of the 17th U.S. Colored Troops. No doubt he was strongly encouraged to come and assist his brother-in-law as obtaining qualified white officers to quickly join the newly formed colored regiments was difficult. Job was later promoted to Captain and Company Commander in the Regiment when a vacancy occurred. It was in this capacity that Job was serving at the time of his death as a member of the 17th U.S.C.T within the 1st Colored Brigade. He was killed early on the opening day of the Battle of Nashville near the railroad cut at Granbury’s Lunette.

I was able to travel down to Nashville in April, stopping along the way at the small battlefield of Tebb’s Bend Kentucky where the unit of my Great-Great Grandfather with the 25th Michigan Infantry fought a pitched battle with General Morgan’s cavalry in 1863. I was able to locate Granbury’s Lunette in Nashville. So that was certainly interesting and I’m glad that the portion of the Lunette still survives and is being preserved.

This spring, we were back at the Shafter cemetery and probed the ground as best we could, looking for some trace of Captain Aldrich’s grave. We were able to locate what we believe is the top portion of a broken headstone. The stone bears no text but does clearly have a Masonic symbol on it. After researching all the other burials I believe that Aldrich was the only Mason who was buried at the site. We also found a small gravestone foundation that fits the broken piece of headstone perfectly. Then, knowing that several of the graves also had footstones associated with them we carefully searched and found an uprooted footstone laying flat under the earth. In cleaning it off with water the initials J.H.A. appeared carved in the stone — Job H. Aldrich! So we feel very confident that we located the gravesite!

Above: View of the Shafter Cemetery looking east. We believe that the small stone towards the rear with the rounded top is the headstone of Captain Aldrich. The stone was found laying flat. We placed it upright on base of stone located in ground. The footstone (with the initials J. H. A.) is visible beyond the headstone. Photo taken May, 2012.

Above: Closer view of broken top of rounded headstone believed to be Captain Aldrich’s. Note the Masonic symbol on stone face. In the background is the footstone that had been toppled. We set it upright. Taken May, 2012.

Above: View of footstone to east of rounded headstone believed to be Captain Aldrich’s. Initial J.H.A. visible (Job H. Aldrich). Taken May, 2012.

Above: Photograph of Ann Eliza Shafter Aldrich’s grave marker, May, 2012.

Above: Photograph of Ann Eliza Shafter Aldrich’s grave marker, May, 2012.

So now I’m going to start trying to obtain a government headstone to mark the site. Given that there are no known living descendents I’m not sure on the success of that but if nothing else I will obtain a regular headstone. The objective will be to get it done by the summer of 2014, 150 years since Captain Aldrich was killed in battle. The local Sons of Union Veterans of the Civil War will certainly assist in getting the stone placed and rendering appropriate honors. I also intend to write up what I learned about the Shafter and the Aldrich families for the Galesburg library and museum so that their stories will not be lost again.

I hope this was interesting to you and again thank you for your time in efforts in helping me learn more about the Battle of Nashville and the role of the 17th USCT. I’ll send few pictures of the Shafter Cemetery in a following message so you can get an idea of what it looks like.

Sincerely,

Joe Mazurek

COL, USAR (Ret.)

Richland, Michigan